A sample of wood waste collected from a residential construction site.

Of all the types of C&D waste that come out of Vancouver’s building industry, wood is by the least well recycled. Wood waste makes up the majority of landfilled C&D waste by volume and its existing recycling pathways are always to downcycle. Vancouver has requirements that mandate specific percentages of a building’s materials be recycled or reused upon demolition. It is not mandated for all buildings but generally only for buildings deemed to contain valuable materials such as old-growth hard wood, or buildings with character status (i.e. buildings constructed pre-1950) For buildings targeting accreditation standards such as LEED certification or other municipal green building standards, there are also requirements to divert a percentage of deconstructed materials from the landfill. Contractors who fail to separate clean (whole, unpainted) wood from waste loads are also subject to higher tipping fees at the Vancouver landfill, however in practice, the additional fees are not enough of an incentive to encourage proper on-site sorting. Companies such as Sea-to-Sky removals who provide collection systems for on-site waste sorting, and Unbuilders who deconstruct and salvage materials from pre-1950s residences are helping to establish a market for more responsible waste management; however, the lack of useful pathways for wood recycling means that very little of it is used for further construction purposes.

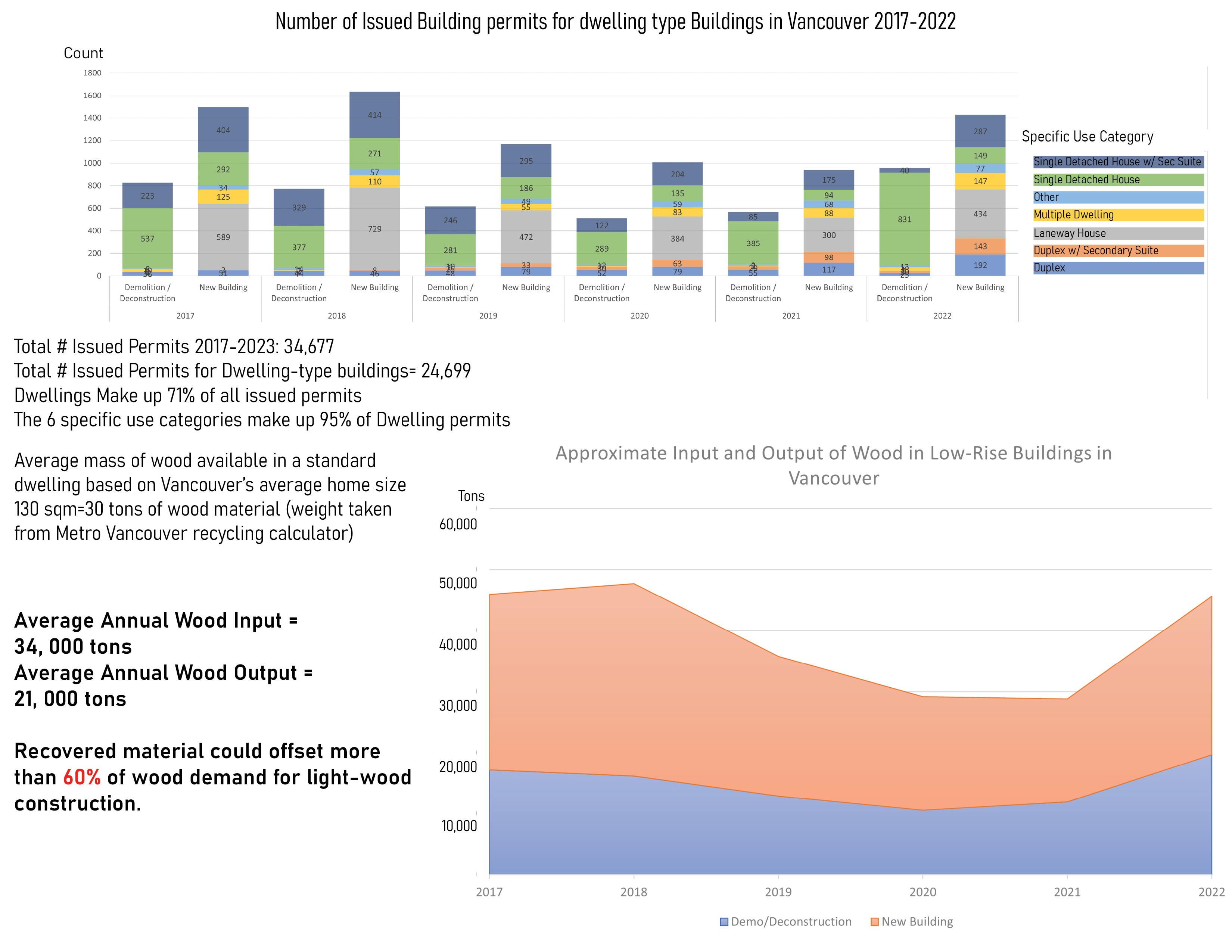

In the last six years (2017-2023) 71% of all issued building permits in Vancouver were for dwelling type buildings and of those 80% were for low to mid-rise structures with light-wood frame construction. If the average dwelling in Vancouver is 130 sqm and contains around 30 tons of wood, then the average mass of wood used in construction in a single year is approximately 34,000 tons and the amount of wood deconstructed is 21,000 tons meaning that by mass deconstructed wood could offset up to 60% of new wood demands in a given year (see chart below for further details). Of course reclamation rates are not perfect and there are many barriers to safely and effectively salvaging wood.

One of the biggest barriers is ease and safety of deconstruction. Houses built before 1950 (which makes up about 33% of the housing stock in Vancouver) are the easiest to deconstruct as they generally higher-quality wood, where constructed using hand-building techniques, and are not contaminated by spray foams and construction adhesives. These buildings generally were built with old-growth lumber which is a valuable material in the market for salvaged materials. Houses built after 1950 but prior to the early 2000s have more complex constructions that include spray foam, adhesive membranes, construction adhesives, and nail gun assemblies which are difficult if not impossible to deconstruct without damaging the buildings materials. Post 2000s buildings generally have decreased use of spray foam which makes salvage somewhat easier, but still make use of nail guns, construction adhesives, and membranes which make deconstruction very difficult. General salvage challenges for all ages of buildings include the presence of toxic contaminants lead and asbestos, and the uncertainty of strength of the wood after decades of moisture-level changes.

Shifting to a method of construction that relies less on permanent, and inseparable connections and reduces the use of adhesive and paint contaminants is a necessary adaptation in the building industry that will facilitate deconstruction and salvage operations at the end of a building’s lifespan. You can click here to read more on specific methods in design for deconstruction. As the city ages it will become necessary to develop deconstruction strategies that encompass even the most difficult buildings and provide reuse and recycling pathways for the salvaged material.