What new books might we write, if we could learn to use objects and spaces, buildings and bodies…to make architecture from words on a page? – Shelly Jackson

This question has guided my deliberations on how exactly to go about doing a final project for this course. I knew I wanted to make a narrative, and one that tangibly interfaced with more than just sheets of paper. I wanted to use the city, and all the facets of its infrastructure not only as a place of radical fantasy, but as a material thing in and of itself. I wanted to write on it and with it – to throw fragments of a narrative across sidewalks and along the walls of buildings, to use the city’s own syntax of doorways and stairwells and multi-level car-parks, to collide text and space in a way that figures reading as a physical praxis. I’d then map it – the narrative – and chart it through more abstract, fantastic and parallel landscapes – digital landscapes, imagined geographies – all woven together as an elaborate hypertext, where the end links to the beginning in a metafictional loop.

After running through this naive and probably over-ambitious, under-developed scenario in different ways, it’s finally been subsumed as a preamble to a project that may prove to be more grounded, comprehensible and, most importantly, doable.

Specifically, my ideas began to change as I focused more on graffiti as a primary mode of displaying the project. The physical act of superimposing an image, or in this case a text-based narrative, over a preexisting surface seemed apt considering the kinds of speculative architectural projects we’ve looked at this term. We’ve looked at a range of megastructural designs from the mid-to-late 20th century that take up collage as means of revising and re-conceiving the urban landscape: Archigram‘s psychedelic cut-and-paste renderings of their Instant City project show a capitalist spectacle of transient infrastructure that could essentially be dropped anywhere, while Superstudio‘s austere Continuous Monument sprawls ominously across preexisting landscapes. Yona Friedman superimposes his constructions as well, literally marking up a cityscape with suspended grids and cables, composing an imagined territory floating overtop of the real.

I wanted to work with the concept of the overlay through graffiti, and realized the most direct way of achieving this would be to actually post the graffiti onto walls, along the lines of swoon or or Shepard Fairey’s Obey (/Obama) posters. I thought of Ballard here, and especially the kind of relationship the Atrocity Exhibition has with visual surrealism[] – employing techniques like frottage and decalomania in his text to represent the collision of technology with the body, as well as the friction that the condensed novels hold against each other within the book. Through its name as well, surrealism also implies a kind of superimposition.

I considered writing short, site-specific stories and then adhering (pressing, rubbing) the pages against the location they narrate, with piles of looseleaf on the ground, as if the walls were shedding memories: A kid drawing pictures in chalk, careless fingers dragged across by passerby, a bloody fight, a hustler’s date, a drifter’s muttered lamentations…It made me realize how there wasn’t necessarily a need for completely fabricated memories – that the city is already marked up with its own stories, the ceaseless flow of people imprinting its own kind of graffiti. The street, the walls, the sidewalks are all documents.

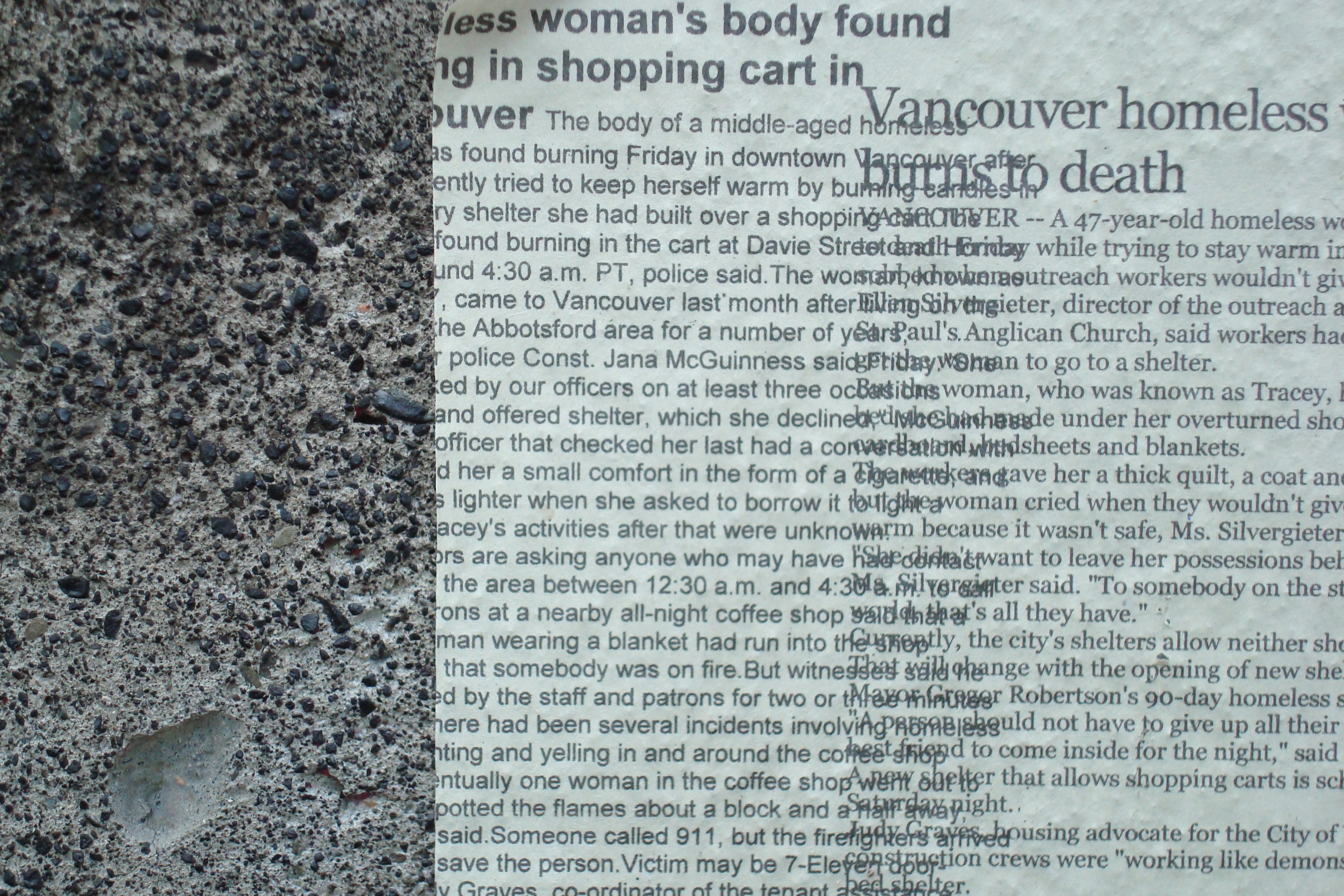

This pulled at a memory of my own – of a news story that ran this past December, about a homeless woman who’d burned to death downtown inside a makeshift shelter, on the corner of Hornby and Davie street. She had lit some candles to keep warm, fallen asleep, and burned alive inside her shopping cart. The absurd, horrific story had almost as much affect as the photographs of the wall the woman had been lying against. It was stained black.

I was, and still am, morbidly fascinated by the mark – I had this impulse after reading the story to go downtown to see it, to touch the soot, to look. And now I ask myself what it was exactly that I wanted to see – it was the news article that gave me the background of the event, its context, location, and most importantly its narrative. I wanted to see the story, or a fragment of it, as manifest in its remains.

The stain itself is an ambiguous black mark, but the words I read in the paper, and the words I’m reading right now in blogs, forums, and international press all act as means of writing the corner of Hornby and Davie street. Specifically, the black mark outlines a territory for this aggregate narrative – a locus or site for the words describing it. I wanted to bring the story a new publicity though, by overlaying a compiled account of it from the public realm of the internet onto that of the street. Alternately, I wanted to tear away the concrete surface of the wall, to expose an imagined underlying narrative structure.

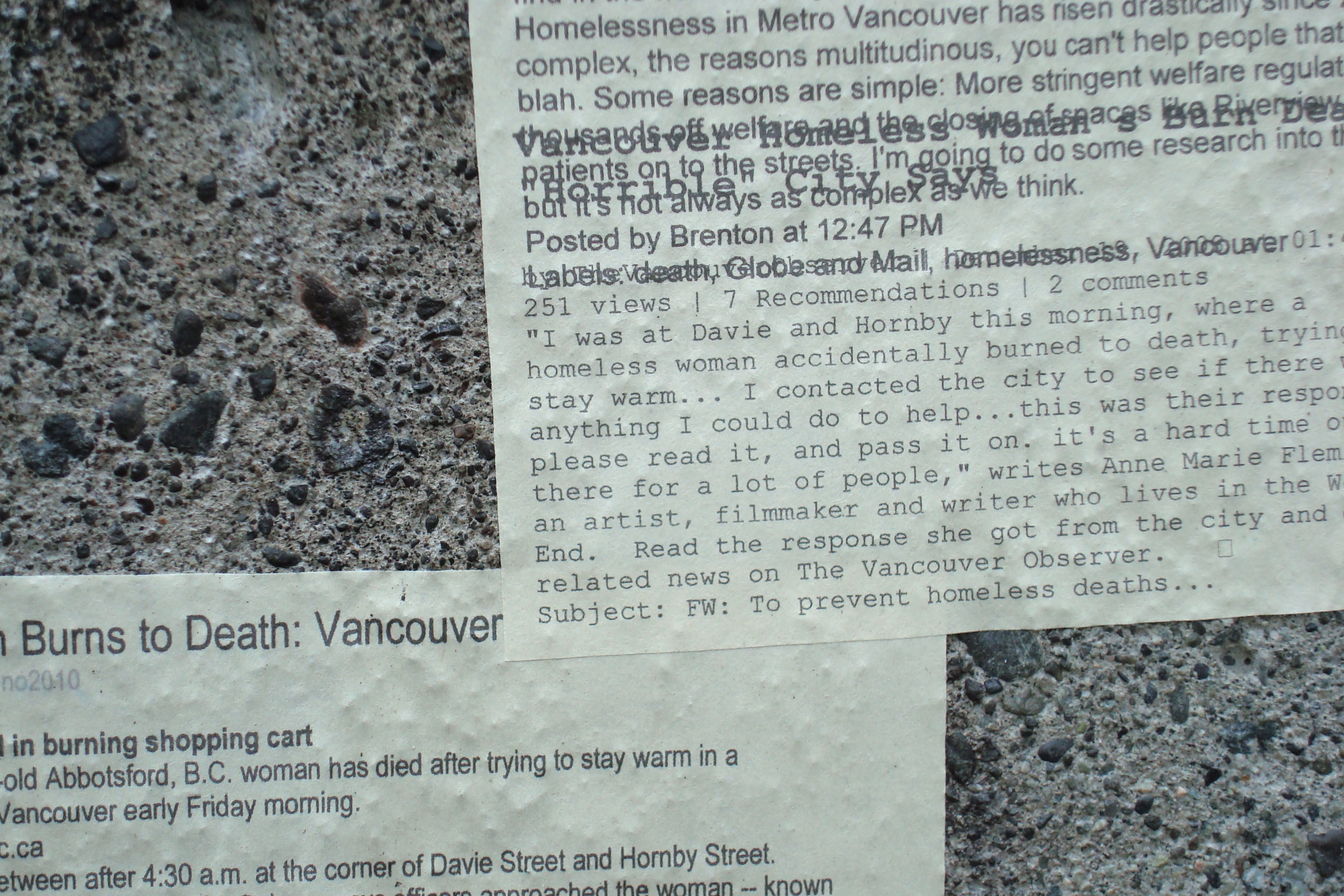

So I filled the space marked off by the burns – an incomprehensible space considering the experience inscribed there – constructing a narrative to fit within the borders of a blackened, unknown territory. I filled it with a patchwork of words distilled from its coverage (online news, blog posts, forums etc.) in a kind of textual catharsis, enabling the possibility of both an analytical and affective process of somehow delineating or mapping the event through words.

[click to enlarge]

[click to enlarge]

Materially, the project outlines changing notions of news-media, printing web content on blank newsprint to gesture at the ephemerality of stories like this, regardless of them being archived elsewhere. It also depicts a major conceit of the seminar – referencing the idea of speculative rendering, or what we’ve been referring to as “paper architecture”. As designer Molly Wright Steeson puts it, “Architectural drawings generate new reality by stealth. The nature of drawing reinforces that architecture doesn’t need to be built in order to create or occupy social reality, a mode of interaction, a way of life.”* Thus, beyond the images and films we’ve looked at this term, the texts themselves function as a sort of paper architecture in their ability radically imagine other spaces, working to influence the conception of real space through their place in the intimate, marginal space of the imaginary. It is in this spirit that I want to think of the text-graffiti on Hornby and Davie as performing – albeit with its overarching purpose as a speculative project made more implicit.

The words pasted to the wall hold a material, visceral relationship to the moment they describe, abutting and overlaying the markings of the fire while melding with the rough concrete. The surface itself is pockmarked by previous attempts of erasure; the black streaks are a kind of graffiti, a defacement, an uncomfortable blemish of a deeply personal event imprinted on a public surface. Perhaps more contentious is the fact that this project itself appears as a kind of co-opting of the wall, an insensitive, even obnoxious detournment of the woman’s death made to further politicize it, or more generally a heavy-handed comment on the city’s actions around homelessness and the ongoing housing crisis. Which, evidently it does, as this is the message most passerby have taken from it. I didn’t fully realize until cutting out the words how this could be seen as a brazen move, but the instillation is accussive through its indexicality – its ability to point both to the site of the woman’s death and to us as we would have walked past it, unknowning. It implicates the viewer, who, once understanding what the marks on the wall signify, is disturbed.

I want to think more about this disturbance – and its weirdness, its strangeness – as an experience characteristic of that generated in science fiction. This is not to trivialize or obscure the moment of her death, but to fixate on the marginalized, alienated position of the homeless woman, who had appeared in the city weeks earlier and was known only as “Tracey”. Her liminality is compounded by the strangeness and unfathomable nature of her death, and framed absurdly by the idea that Vancouver is one of the most livable cities on the planet. One journalist responded to circumstances of Tracy’s death and the poverty that defined her life by stating, poignantly, that “It is truly another world.”

As this idea of ‘other worlds’ too figures prominently in science fiction, (where a large part of the genre’s work consists re-imagining and conceptualizing alternate places, states and subjectivities), the critic Darko Suvin puts it into clearer focus, defining SF as a genre whose “conditions are the presence and interaction of estrangement and cognition, and whose main formal device is an imaginative framework alternative to the author’s empirical environment.”* Put simply, science fiction estranges, but in a rational voice. Considering the fact that Tracey’s death is explicated both in the rational/objective style of news-media, and on a more fundamental level through the simple rationality of print (over that of the visceral markings of the fire), It is possible, then, to consider the graffiti installation as in itself a site of cognitive estrangement.

To be estranged is to be distanced or removed from the familiar, which leads to wondering where – beyond simply the “unknown” or “unfamiliar” – we are placed or constructed as subjects. In addition to the surface-narrative made by the posted material – the description of the Tracey’s death – an internal narrative develops between us and the work that is particular to the experience of cognitive estrangement, and further contingent on the space or site in which this narrative takes shape. There is, then, a dynamic at play between the site, the viewer and the viewer’s imagination that begins to define what we might call the site’s ‘narrative space’. “Narrativity” writes Anne Lovell, a medical anthropologist whose work deals with psychiatry and social marginalization, “is a social space in which a person, in interaction with real or imagined others, actively engages in constituting his or her subjectivity or self.” In other words, narrative is spatially contingent. We in turn are moved or “placed” into a particular position. Considering the possibility that graffiti, for example, and this project in particular, can draw out scenarios of estrangement, this may in turn afford us – the pedestrian audience – an alternate and inter-subjective standpoint.

This is not to say we simply observe the wall from our own subjective point-of-view on the sidewalk, or that we are afforded a narrative perspective aligned with Tracey’s subject-position either. Instead, the project constructs within the site an interstitial place from which our own personal narratives of it take shape, centralizing the narrative of Tracey’s death by fixating on the site as itself a textual and narrative medium. What sense could be made of urban space and the people that inhabit it through a situated imagining of one moment in the city?

[]

Discussed in detail by Roger Luckhurst in The Angle Between Two Walls, specifically in the section “The Atrocity Exhibition as Avant-Garde Composition” (p. 86-94).

Works Cited:

Fowler, Bo. “The Science of Fiction.” New Humanist. 116:1 (2001) <http://newhumanist.org.uk/437>

Lovell, Anne M. “The City is My Mother.” American Anthropologist. 99:2 (1997): 355-368.

Luckhurst, Roger. The Angle Between Two Walls. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997.

Wright Steenson, Molly. “Architectural Drawing as a Stealth Tactic.” Active Social Plastic (Blog). August 27, 2007. <http://www.activesocialplastic.com/2007/08/architectural_drawing_as_steal.html>

Works Consulted:

Patrick Parinder (ed.) Learning from Other Worlds. Durham: Duke UP, 2000.

{ 1 trackback }

{ 0 comments… add one now }