Background

Traffic congestion is costly to individual as well as society. To In 1975, Singapore operated a manual road-pricing scheme called the Area Licensing Scheme (ALS), which was the world’s first pricing scheme. This scheme required motorists to purchase a paper license and display it to the enforcement officer before entering a restricted zone (RZ). In 1995, the ALS was replaced by an automatic Dedicated Short Range Communication (DSRC) system called the Electronic Road Pricing (ERP) scheme. The main components (See Figure 1) are the In-Vehicle Unit (IU), a notebook sized device fixed on the windscreen of vehicles and a CashCard. The different features between ALS and ERP are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1. Singapore’s new dual-mode IU with a CashCard

Source: Courtesy of Singapore Land Transport Authority

Table 1. Summary of Features

ALS |

EPR |

|

Enforcement |

Manual |

Cameras |

Demarcation of Area |

Cordon |

ERP Gantry (see picture Figure1) |

Payment |

Cash |

Smart Card |

Identifier |

Paper License (Different shapes for different vehicles and color codes for different months) |

Electronic Tag (IU) |

Operating Hours |

Restricted hours of 7:30am-9:30 am, but not for Sundays and public holidays |

The whole day |

Violations |

Heavy |

No IUPenalty of S$70=US$58No CashCards or Insufficient value in CardAdministrative fee S$10=US$8.28. (Lower fee if paid via e-Payment services |

Exemptions |

Taxis (later removed), public transport, buses, goods vehicles, motorcycles, and passengers |

The emergency vehicles(cannot find the specific items) |

Disadvantages |

Cumbersome, labour-intensive and inflexible |

Privacy maybe violated.The revenue is lower than revenue raised under ALS |

Advantages |

Car-polling was a good way to optimize vehicle usage and save money. |

Improve capacity AND smooth the rideConvenience, time saving AND RELIABLE |

Resource: This table is built based on http://www.ibtta.org/files/PDFs/Chin_Kian%20Keong.pdf

Figure 2. An ERP Gantry in Singapore

Source: Courtesy of Singapore land Transport Authority

Figure 3. ERP Working Process

Resource: http://www.lta.gov.sg/content/ltaweb/en/roads-and-motoring/managing-traffic-and-congestion/electronic-road-pricing-erp.html

ERP Rates

According to the Land Transport Authority (LTA), “ERP rates are determined by a quarterly review of traffic speeds of priced roads and during the June and December school holidays.” The LTA concluded that the prices are charged mainly based on two parts: Passenger Car Unit (PCU) equivalent and the time entering RZ. (See Table 2) Besides, the motorists should control their speeds between 20km/h to 30km/h on selected ways and between 45km/h and 65km/h on expressways.

Table 2.Two parts of Charges

|

PCU equivalent |

The time entering RZ |

| Cars, taxis and light goods vehicles are 1PCU. Motorcycles are 0.5PCU; heavy goods vehicles and small buses are 1.5PCU. Very heavy goods vehicles and big buses are 2PCU. | During peak hours, charges change every half hour to take into account traffic volumes. This helps to spread the traffic flow over a longer period. |

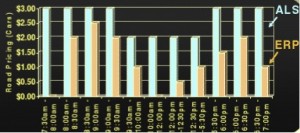

We can see that the ERP rates vary for different time and roads periods and can be adjusted based on local traffic conditions. From Figure 3 we can see that 9 Am is an expensive time to drive, but in noon the rate is very cheap. For some alternative routs, the motorists don’t need to pay any fees. Therefore, this scheme encourages the motorists to make adjustments on their mode of transport, time of travel and travel route. The ERP scheme is very flexible and adaptive. However, some problems appeared. For example, to avoid higher charges time, some motorists would wait until the cheaper period started. To solve this problem the LTA introduced graduated ERP rates, which introduced a new rate for the last five minutes if the next period has a lower ERP rate.

Figure 3. EPR Rates and ALS Rates

Resource: http://www.ibtta.org/files/PDFs/Chin_Kian%20Keong.pdf

The effectiveness of ERP

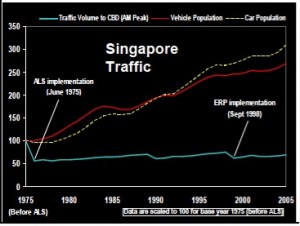

1) Traffic Impact

After replacing the ALS with ERP system, traffic levels have decreased a further 15 percent. In Figure 6, the traffic volume into the Central Business District (CBD) showed a significant decrease from 1975. Although the vehicle population and car population had been increasing, the traffic volume almost stayed unchanged and also showed a small decrease. In Singapore, increasing number of citizens chooses public vehicles as their main transportation tool, round 63% by public transportation.

Figure 6. Traffic Volume Changes

Resource: http://www.ibtta.org/files/PDFs/Chin_Kian%20Keong.pdf

2) Costs and Revenue

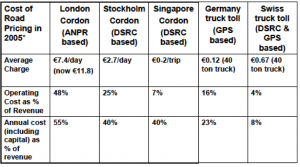

From Figure 5, we can conclude that compared with other countries, Singapore had very high ratio of annual cost to revenue, which results from high purchase and installation cost of ERP equipment and UI. However, the operating cost was very low. Singapore’s ERP system is operated by the control center Compared with other countries’ scheme, the ERP system is flexible and not labor intensive. As Walker (2011) showed, “the cost of managing and maintaining the ERP system has increased over the years, consistent with the increase in the number of gantries and IU numbers, but remains at 20–30% of total revenue collected, the objective is traffic management, not revenue generation.” For example, between 2007 and 2009, ERP revenue increased by $44 million, but at the same time, the additional registration fee (ARF) and vehicle tax revenue fell by $329 million in total. The revenue from the system is mainly used for construction and maintenance of roads and public transportation.

Figure 5. Cost-Effectiveness Matters

Source: European Conference on Transport Minister, 2006, http://www.cemt.org/topics/taxs/Paris06/Conclusions.pdf

Conclusion

In Singapore, technology has brought a lot benefits to the society. I think ERP is a very effective road management tool, which could be a lesson for other countries. The revenue neutral of this scheme avoid the fight from citizens. The motorists can enjoy a smoother drive, change their schedule to pay lesser charges and choose an alternative road. When we analyze the benefits of a road pricing scheme, we should think about externalities such as time saving, higher speeds, CO2 reduction, Fuel saving and also alternative road’s congestion problem. In my blog, I cannot get enough information on this point. In London’s case, we can have more sense of how to measure the efficiency of a road policy.

References:

Land Transport Authority http://www.lta.gov.sg/content/ltaweb/en/roads-and-motoring/managing-traffic-and-congestion/electronic-road-pricing-erp.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Road_pricing#cite_note-34

John Walker(2011), The Acceptability of Road Pricing http://www.racfoundation.org/assets/rac_foundation/content/downloadables/the%20acceptability%20of%20road%20pricing%20-%20walker%20-%20main%20report%20(may%2011).pdf

ERP System in Singapore http://duniainformation.blogspot.ca/2012/11/erp-system-in-singapore.html

http://www.imprint-eu.org/public/Papers/IMPRINT3_chin.pdf

http://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop08047/02summ.htm

http://www.cemt.org/topics/taxs/Paris06/Conclusions.pdf

http://www.ibtta.org/files/PDFs/Chin_Kian%20Keong.pdf

http://www.dac.dk/en/dac-cities/sustainable-cities-2/all-cases/transport/singapore-the-worlds-first-digital-congestion-charging-system/?bbredirect=true