For this blog, I will examine the references in Green Grass, Running Water from pages 38 to 48. These pages cover several of the different stories at play during the novel, and offer insight into some of the larger themes. In particular these pages all interrogate some aspect of settler perspectives of themselves and Indigenous people.

The first section begins with a conversation between Coyote and God/dog, who Flick claims to represent the God of the Old Testament, something supported by his authoritative behavior. In their conversation God expresses confusion regarding the trajectory of the story, namely in how it differs from how it is told Old Testament. God repeatedly asks “where the water came from” (King 38) . While I had initially failed to understand what the potential meaning might be, reading the scene as written in the Old Testament gave me an idea. In Genesis 1 where God creates the world, water is never mentioned. Instead after creating light and darkness God creates “an expanse between the waters to separate water from water” (Genesis 1) or sky. Perhaps by pointing out a plot-hole in the the text which settlers have used to justify their colonialism and marginalization, King is able to interrogate its mythos. The story continues, bringing up the First Woman, who falls from the Sky World to the Water World. Once she falls near to the water world, a group of ducks place her on the back of grandmother Turtle, and after proceeds to put mud on grandmother Turtle’s back. Afterwards, Old Coyote suggests the need for a garden. In the garden, a man named Ahdamn appears inexplicably, and begins to name things incorrectly. To pacify him she gives him an apple, which frustrates God/dog.

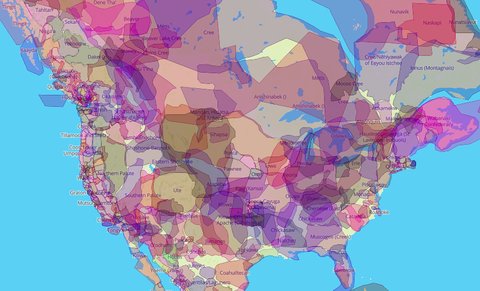

This passage juxtaposes two different creation stories, the one in the Old Testament and the creation of Turtle Island, which comes from Indigenous storytelling. The two stories challenge and contradict each other, just as God, does to Coyote. As is evidenced by my citation on the Old Testament, much scholarly effort has been applied towards understanding and contextualizing his behaviors. Less effort has been applied to Indigenous creation stories in terms of celebrating the nuance of them. But through comparing them, particularly through an Indigenous viewpoint, shows the nuance inherent to the stories from aboriginal cultures. Through the alternate perspective, the same events are also shown in a different light. In the Turtle Island Myth, women play a prominent role with both the First Women and grandmother Turtle, and they are highly capable, whereas Ahdamn, is effectively useless. In the biblical story, Eve is blamed for the fall of man, since in Genesis she forces Adam to eat the apple, something which has been used to justify the historic mistreatment of women. In Green Grass, Running Water by having the First Women, not only be competent and valuable, shows an inherent flaw in how settlers have chosen to interact with and interpret their mythos.

The next story returns to Alberta Frank, whose significance as a geographic location has been much discussed by Flick. She asks Charlie if she can bring Lionel with her when she visits him. Alberta is having affairs with both men, and uses them to satisfy her needs without seeking commitment. The also represent the settler-colonized binary, while both are Indigenous, Charlie works as a lawyer who helps to perpetuate colonial land practices while Lionel, according to Charlie is only a few years short of returning to the reserve to run for “council” (King 43). In essence Alberta’s “choice” and Charlie’s categorization of both men suggests the limited framework by which Indigenous people are characterized by settlers, either as “progressive” by working for settler interests or “regressive” by continuing to stay on reserve land and engaging with Indigenous community practices.

The final section returns to Dr. Joe Hovaugh, who is trying convince Dr. John Elliot of four old “Indians”. He claims their disappearances preceded disasters like the stock market crash which lead to the great depression and the eruption of the Saint Helens and Krakatau volcanoes. But as Elliot points out, there were plenty of dates that had no significant event. Regardless Hovaugh remains convinced that a pattern is there, and brushes Elliot off, as he thinks Elliot thinks this is a game comparative to Cowboys and Indians. The chapter ends with Elliot asking, several questions about where they went and why, as well as why they would want to leave in the first place.

This passage has two white authorities, whose names have been taken from Christian messages and missionary who converted Indigenous people to Christianity, attempting to understand Indigenous spiritual figures, but ultimately failing because of their refusal to step outside their own limited perspective as settlers. For instance, Hovaugh’s rejection of the idea that there is no specific connection tied to the date of disappearances mirrors the behavior of settler theorists when presented with contrary knowledge, something I have discussed in an earlier blog. In essence, Hovaugh and the people he represents will never truly be able to comprehend beliefs and actions of Indigenous people when considering their actions through the perspective of settlers.

Works Cited

“An Aboriginal Presence.” Civilization.ca – First Peoples of Canada – Our Origins, Origin Stories, www.historymuseum.ca/cmc/exhibitions/aborig/fp/fpz2f22e.html.

Bonikowsky, Laura Neilson. “Frank Slide: Canada’s Deadliest Rockslide”. The Canadian Encyclopedia, 25 January 2019, Historica Canada. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/frank-slide-feature. Accessed 19 March 2020.

“Cowboys and Indian.” Merriam Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/cowboys and Indians.

“Encyclopædia Britannica.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.https://www.britannica.com/biography/Adam-and-Eve-biblical-literary-figures

“Encyclopædia Britannica.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1 Jan. 2020, https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Eliot-British-missionary.

Genesis 1 web.mit.edu http://web.mit.edu/jywang/www/cef/Bible/NIV/NIV_Bible/GEN+1.html

Mark, Joshua J. “Yahweh.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 22 Oct 2018. Web. 19 Mar 2020.

Laie, Benjamin T. “Garden of Eden.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 12 Jan 2018. Web. 19 Mar 2020.

Robinson, Amanda. “Turtle Island”. The Canadian Encyclopedia, 06 November 2018, Historica Canada. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/turtle-island. Accessed 18 March 2020.

Strawn, Brent A. “God in the Old Testament.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. . Oxford University Press. Date of access 19 Mar. 2020, <https://oxfordre.com/religion/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.001.0001/acrefore-9780199340378-e-4>