Underdogs is a novel that looks at the Mexican Revolution through the perspective of the revolutionaries who were fighting against the government. There were those supporting Zapata in the south, and those supporting Villa in the north. Both though were revolting against Porfirio Diaz dictatorship which had taken away their land. Therefore, one of the key defining aspects of the Mexican Revolution was this fight for land, for land was not only a part of identity, but it was also a symbol of wealth, a means to cultivate and trade with others their agricultural goods. It was also, however, associated with having a job and was also deeply tied to family life. Therefore, not having land was not just a problem; it also posed a threat to family life and survival who without it would have no means of food, or wealth to buy things. This problem goes back to our discussion on the Communist Manifesto in regards to inequalities, expropriation of land, and class struggles between the bourgeoisie (who in this case is the government) and the rural proletariat (the campesinos or famers). This blog is not intended to be historical or explanatory, but to emphasize once again certain recurring themes such as class struggle, revolutions, land, inequalities, power, and capitalism. I would however like to bring to attention some things that I found interesting about this novel. To start off, I would like to talk about the names of the characters, some of which have this high-status, honorable connotation. For example, Demetrio, Anastasio, Pancracio, War Paint, and Luis Cervantes who got his name from Miguel de Cervantes who if you don’t know, was a very famous Spanish writer, also author of Don Quijote. It seems as if by giving the characters these well-thought of names, the author is giving more meaning and clarity into the revolution and its cause. There is also something I appreciated about this novel, and that is how the novel challenged our assumption that the revolutionaries were the “good guys” because they were fighting to bring change and put an end to the despotic regime. What this novel also shows is the more personal stories of the revolutions that we don’t often find in history text books. The revolutionaries it seems were also bad (men) in that they stole, destroyed, and abused women throughout their journey, sort of like scavengers who do not care about the consequences they have on others just that it serves them in some way. This then relates to the title, Underdogs. The title can be directed not only at the Federales or the government itself, but also at the revolutionaries. This revolution, depending on how you look at it, and to what extent you are affected by it, is a story not about humans fighting humans, but of animals fighting animals as neither side behaved well. What I also appreciated about the novel was the numerous references to nature. This is important because once again, land (and nature) played a huge role in people’s lives. It was part of identity, but also of culture. The many references to nature only makes this revolution more of a personal story where people are fighting for something dear to them as they do not want to lose that. As part of the “personal” story, I like how the novel also engages us in the conversations that these soldiers had. History books also don’t tell the conversations, or stories that soldiers shared amongst one another. Certain topics in the novel would come up such as family, fear, politics, humor, songs, money, etc. This once again shows that the revolution is not just about fighting, but it’s about people. As a side note, one other thing I found very interesting was how in one part of the novel, it mentions that there are 2 things men fight to protect: family and their country. We can now add to the Mexican Revolution, this concept of fighting for families as well. And finally, I would like to end with a quote found on page 43 where it says “the revolution is a fight for principles and ideals, not to kill”. I think this challenges one of our main conceptions of revolutions as being violent. According to some people, they don’t want to fight, kill, or cause anyone any harm. All they ultimately want is change, ideals, principles; peace. People make revolutions violent, but it is not necessarily the case that the revolutionaries are for the sole purpose of inflicting pain.

Author Archives: Syndicated User

noticing commonalities

I felt that the notion of revolutions are cyclical and doomed to recreate and/or sustain the conditions they were conceived in really came through in this novel, especially in the latter half. This sentiment is encapsulated by a phrase near the end of the book which reads, “”If you’ve got a rifle in your hand and your cartridge belts are full its because you’re going to fight. For whom? Against whom? For whom? No one even cares about that.” (Pg 78) In this instance, revolution, and specifically its violent qualities, are seen as mindless and mechanical. The fighting loses its meaning. We see this again when Demetrio’s wife asks him why he is still fighting and he replies, “see how the pebble can’t stop…” (Pg 86) Positing what began as revolutionary violence as not only inevitable but natural as well.

When Demetrio and his crew begin looting more regularly, we see a much darker side of them than we did before. Or perhaps we only see it pronounced in comparison to the first half of the book. Eventually while looting they “clean out” a peasant man. They take all his corn and he cannot feed his family. When he brings this to their attention they make a show of accommodating him but then make him “beg for mercy.” (Pg 68) This scene puts into focus, who, if anyone, Demetrio & his gang appear to be fighting for. At this point, it seems that they are only fighting for themselves. What is telling about this scene is that they are not only unwilling to meet this man’s needs but they actually make a spectacle of his suffering.

Luis Cervante does a curious thing in the same scene. When the looting is over he says, “Look what a mess the boys have made. Wouldn’t it be best to keep them from doing this?” (Pg 48) He is condemns looting but as readers we know he himself has pocketed one of the most valuable things found, diamonds. (The person he’s talking to also knows this but declines to comment on his obvious insincerity.) Cervante maintains an air of superiority throughout the story which reaches its peak when we learn he has taken his spoils and enrolled in medical school in America. It seems to me that in this scene especially he is demonstrating a double standard. He appears to feel moral/intellectual superiority even though he engages in similar and/or identical activities as his peers. What I found strange is that when I looked into the author’s background it was very similar to Cervante’s in that the author also had a background in academia and in medicine. This portrayal then confused me because I couldn’t tell whether the author’s intent was to demonstrate the precarity of Cervante’s superiority or the legitimacy of it.

Viva Zapata – presentation outline and reflections

Thank you all for working with George and I on Thursday and engaging with our discussion questions. It would have been a lot more difficult to do that class if no one was into talking. Anyway, our meta outline for the class was :

- George would talk about Zapata and Plan de Ayala

- I would talk about what differentiated Zapata’s movement (land)

Two videos –

Zapatistas-

Unistoten-

- In what ways is Zapata’s revolution different from a traditional Marxist revolution?

- Is there room for indigenaity in a Marxist revolution?

- What advantages/disadvantages do movement have that are centered around land.?

- George would connect that movement based in land to the EZLN

As far as the parts that we did get too, I thought it went very well. I really felt the discussion about the paintings that George showed was interesting and I appreciated the discussion around room for indigenaity in Marxist movements. For the next time I will have a better idea of how long the discussion will take and plug my computer in so that it doesn’t die in the middle of the presentation.

Now, for the part that I didn’t get to-

– I planed to finish up by talking about the way the Neo-Zapatista movement has been represented/romanticized and finally think about how we can engage in a positive way with contemporary movements that are in the global south.

Quote from: Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective Actions, Theories, and Critical Reflections

In what ways does Romanticization/simplification undermine a movement?

What are the advantages/disadvantages to have an idolized leader/martyr?

How can you engage in a meaningful way with a movement that is in the global south and resist the move to romanicize/simplify?

Quote from a paper by Juanita Sundberg (ubc geography) on North South solidarity –

As posed by United Statesians or Canadians, the question “how can we help” suggests that solidarity is about helping to defend the rights and freedoms of differently situated others. The answer developed by H.I.J.@.S. members suggests that such rights and freedoms are not natural to places like the US or Canada, but are derived from political struggle and therefore can be taken away. In persuading Canadians or United Statesians to become active in struggles for well-being and dignity in their own communities, H.I.J.@.S.-Vancouver are not suggesting that they turn inward and focus on struggles at home rather than abroad. Instead, the idea is that if people in the North try to work from their own experience then they will be in a better position to listen to and collaborate with others involved in equivalent struggles in different locations.

…..Mutuality in solidarity encourages individuals and collectives to speak for themselves, while walking with others to contest neoliberal models that privilege the concerns of multinational corporations over those of civilian populations. We offer these reflections in the hope of inspiring ongoing efforts to re-think solidarity and re-configure resistance through collaboration across borders.

Thanks again to you all and hopefully it goes well this week too!

Week 4 -The Underdogs

The Underdogs, a novel by Mariano Azuela, tells a fictionalized story of a small rebel leader, Demetrio Macias. Overall, I found this book to be rather repetitive, with events rolling into each other. Although, there are several parallels to Viva Zapata! Jose brought up the machismo ideology in his Zapata blog post, and it is very evident in this book as well. Every single time someone brings up an act that they did, be it stealing, bedding a woman (which they of course treat like property), or killing a Federale, it almost always leads to several other men with the need to share their stories, embellishing freely. The men under Macias take what they want – women, jewels, trinkets, etc. as their “advances” for fighting in the revolution. This reminded me of Zapata’s brother who took land because he “earned it” becoming a general. However, unlike Zapata, Macias is very removed from the political purpose of the revolution, as it is shown several times throughout the book that he is not interested in such matters. In reality, he is doing little more than fighting and pillaging for the sake of it, essentially a bandit. He isn’t really fighting for any sort of greater purpose, with no desire of change.

Another parallel that I noticed was when Macias denied his men from plundering a house. He has a flashback to when his own house was sacked and burned, perhaps realizing how similar his own actions are. This reminded me of the role reversal that Zapata experiences when he deals with countrymen who’s land was taken from them. However, while Macias does not let his men take from the house, he still has it burnt down, which confuses me. Unlike Zapata, who goes to confront his brother, Macias does the exact same thing as was done to him.

Yet another moment that was similar to the movie is when Macias returns to his wife, and she begs him not to keep fighting, as she knows something will happen to him if he leaves again. But just like Zapata did in the same situation, he continues on his path dies. Thought it seems that Macias never grasps the ideas of the revolution. Maybe he never believes that anything will come of the revolution, other than another person will come into power, another face on a bill. So instead he takes it upon himself to get what he wants, by force. They build themselves up like they are in the right, that what they are doing is somehow good, but in reality they are no better than the Federales that they fought against. Ironically, by the end a lot of Macias’ followers are ex-Federales.

First Presentation (Mexican Revolution) – Personal Thoughts

The plan for today was to talk about the Plan de Ayala, Indigenous communities, and the EZLN Zapatistas. Firstly, in regards to the Plan de Ayala, I wanted the class to have read it and been able to outline some of the key things Emiliano Zapata mentions such as denouncing Francisco Madero, asking him to step down, explaining why the Mexican system is not working, and land reform. Then I wanted to leave with some questions such as whether or not Zapata’s dream of land reform was successfully achieved, why or why not, or to what extent? Also, I wanted to see how we can relate the Revolution to this notion of indigenismo. What indigenismo is and what role it played in the Revolution. Overall, I wanted the class to get a good understanding of the Plan de Ayala so that I could address more important and current themes such as the EZLN, forms of representation such as murals, and finally the symbolic or personal meaning land has to the indigenous culture, and also identity.

The murals that I showed in class are meant to show that beyond words written in books or spoken orally, the Revolution was imagined and brought to life in different forms such as art and music, all having a lot of symbolic and personal meaning to many Mexicans. Even the fact that some of the murals are currently in the Presidential palace in Mexico is indicative of its impact on forming a part of Mexican history and identity

I was happy that everyone in class already knew who the EZLN were. We know that they are a movement, depending on whose perspective, some say a guerrilla movement, others say indigenous movement. Regardless, they became public when they took over several villages in the southern state of Chiapas, Mexico. More significantly, on New Year’s Day, after the signing of this free trade agreement called NAFTA. They saw NAFTA as a threat to Mexican sovereignty, where Mexicans would suffer under yet another wave of capitalism, ultimately leading to greater inequality. Their 6th Declaration of the Selva Lacandona mentions the problems of capitalism and the exploitative process it carries along with it. They also mention how they want to have more representation or voice in the government, and more access to basic services such as health, and education. Land was once again brought up and the EZLN in fact took its name from Emiliano Zapata. Aja mentioned this in class, and I was also going to ask, but what reason could we think of, that would make them use Zapata’s name as part of this movement? Was it simply continuing on this myth or iconic figure of Zapata, was it about land, or was it something more deep? I also found very interesting the symbolic meaning behind the masks they wore to cover their faces. Some would consider it defiance, others as form of identity protection, and at a deeper level, signifying their “facelessness” in the eyes of the Mexican government. The EZLN also make murals of them and which I think is fascinating and something that could be discussed more as there are probably lots of deeper meanings in them.

Lastly, we’ve been talking about land and land reform and how the Mexican people want it given back. But I would like to address the more personal or symbolic meaning behind land. We did not have time in class to discuss this. The Mexican people don’t just want the land given back to them, just because it’s their home. There is much more. For example, these people for many years have built a relationship with the land, working on it, caring for it, receiving from it. It builds this certain bond. Mexicans also come to think of themselves tied with the land, something that is part of their identity. This is not just the case with Zapata, Pancho Villa, or other campesinos, the fact is, Mexico, throughout its history, has actually lost a lot of its land to others. First Spain during colonialism, then the US where they lost Texas, Arizona, Southern California, and New Mexico. And now with globalism, they see their land being sold to business men around the world. So land is strongly associated with Mexican identity and history. And up to this day they keep on fighting for it.

Has the Revolution ended? What are its legacies? The answers to these questions depend on what side of the story you take. The spirit of Zapatismo, I argue, still exists, and that is a legacy. And the Revolution, if based on land reform, is yes still on, and has never ended.

A Man With a Mustache

Although I somewhat enjoyed the movie Viva Zapata, there were things about it that I just didn’t enjoy. The movie overall does do a good job at telling the tale of the Mexican Revolution through the eyes and events of Emiliano Zapata and the struggle to liberate the lands of the peasants from the rich aristocrats. As the movie progresses we see the transition of Zapata from a lowly field worker to eventually becoming one of the leading figures in the Mexican Revolution. Even with Zapata mentioning at the start of the movie that he did not want to become the conscious of everyone, he eventually finds himself at the center point of not just the indigenous movement but of the revolutionary ones as well. This innate ability to draw people to him which is averagely done in the movie is what allowed for Zapata to become a prominent figure in the Revolution. Eventually becoming an almost immortalized figure in both the revolution and in Mexico.

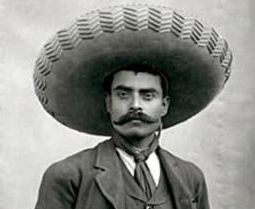

Even with the movie retelling the story of the revolution to somewhat of an accurate degree, there were aspects to it which did not fall within the narrative of true events. These narratives which are used only to further the Hollywood ideologies and such can be seen when Zapata first enters the presidential palace and asks the president for him to act in their staid because the courts take to much time, only for this scene to occur later on in the movie but with the roles reversed and Zapata being in the presidential position. Also, something that I personally could not get over was the lack of mustache that Marlon Brando had. The Mexican Revolution by some can be seen as one of the greatest examples of machismo in Mexican history, Machismo being the ideologies and characteristics that define what it means to be a man. Most importantly presenting yourself to those around you as being the manliest, this can be evident at times with how the men of Zapata are constantly flirting and being with women to an extreme. One of the strongest figures of machismo throughout the revolution was the classic handlebar mustache which can be seen below, the man bellow is the actual Emiliano Zapata, as you can tell his mustache is quite full and a true figure of machismo unlike Brando’s. Although this may seem as a small detail, the concepts of machismo are deeply embedded in not just the Mexican Revolution but in a lot of Latin Culture. At times, machismo can be seen as one of the defining characteristics of the revolution yet Brando lacks the true essence of it the quintessential mustache.

Viva Zapata! and the Mexican Revolution

This week’s assigned work was centered on the movie Viva Zapata! John Steinbeck, a prominent leftist figure in Hollywood during the 1950’s, wrote the movie. I have to admit, the Mexican revolution was one that never really drew the same curiosity out of me as other revolutions.

The movie does a great job of captivating its audience and highlighting the true focus and rationale behind the Mexican revolution, notably the struggle for land in Mexico. The movie was also refreshing in how the characters in the movie were based off real individuals. Often times when cinema produces films or shows regarding revolution or revolutionary individuals it seems that historical persons are exchanged with fictional characters that vaguely resemble their actual counterparts. This has always been odd to me. It is as if the mere mention of revolutionary individuals is villainous or reprehensible in the public’s eyes. Regardless, Viva Zapata! contains important individuals surrounding the revolution such as President Porfirio Diaz, President Victoriano Huerta, President Francisco Madero as well as revolutionaries such as Emiliano Zapata (played by Marlon Brando) and Pancho Villa.

The portrayal of Zapata as a selfless and caring individual is important, as it helps to show a true quality of a revolutionary. A revolutionary must be willing to die for his or her cause, but what Viva Zapata! does so brilliantly is to show the humility and morality of a revolutionary. Zapata is constantly shown as being caring of the peasants he is fighting for. Continually he is portrayed as a concerned individual who is willing to put the desires and needs of the people above his own. Steinbeck also uses Zapata to show the power of corruption and the importance of popular support in a revolutionary movement. Near the end of the film, prior to Zapata’s death, he delivers an interesting quote proclaiming that a “revolution does not need a strong man to lead, but strong people can survive without a leader”. I think this is very important because, while I strongly believe in a revolutionary vanguard, it notes that the backbone of a revolution stems from the people themselves. Of course initially the vanguard revolutionaries will be the ones who initiate armed struggle with the state, it is the people (the peasantry and proletariat) who are the ones with the ability to see a revolution through till the end. Revolutionary motivation comes not from an individual or group, but rather as a violent, explosive and evolutionary outburst of proletarian reaction to the crisis of capitalism. In this way, Viva Zapata! exemplifies the notion that revolution stems from popular discontent, and can only be achieved through popular action.

Viva Zapata!

Before watching the movie about Emiliano Zapata I knew pretty much nothing about him and his movement and the Mexican revolution. It was never a topic that I studied at school or university. Obviously a fictional movie might not be the best way to be introduced to Zapata but there are definitely some things I can take from it. Mostly they come in the form of quotes and scenes about leadership. I thought the most interesting scene was when Zapata is general and a group of men come to him with a land dispute. Zapata says something around the lines of “time will take care of it”, and someone angrily protests saying they don’t have any patience. Zapata then asks the protestor for his name and he circles it on a list, identical to the first scene of the movie where Zapata is the protestor. I thought this scene was critical because it shows perfectly how difficult it is for one person to command over land with people. Zapata himself is shown how hard it is to take things into one’s own hands and please his own people when one is in such a high political position, and this is why he tells the group to be patient. The scene shows how frustrating it can be to hear things like this from politicians and Zapata experiences it firsthand. He was once the revolutionary who went against the status quo and probably called out politicians for being incompetent, but then he himself is being incompetent in the eyes of that group of men when he becomes general.

There were also some good quotes in the movie that stood out and I wrote down. One is around the 22-minute marker when somebody says “you can’t be the consciousness for everybody”. Similar to this, I think it’s Zapata who says “I don’t want to be the consciousness of the world, I don’t want to be the consciousness for anybody”. This made me think of presidents throughout the world. It might seem rather obvious to write this but nations are put on the shoulders of one man or woman, granted, lots of people are involved in a country functions but at the end of the day we all point the finger at one person. The notion of leaders is pretty much following that one persons consciousness. Today it’s hard to say how much of a leaders consciousness directs his actions since political agendas are more important, but in Zapata’s case I think that his consciousness led him to fight for what he believed was right. This leads to my next quote from the movie that is, “a man can be honest and completely wrong”. When I read this quote I am inclined to relate it to the dilemmas of leadership. One person’s view of “right” is another persons “wrong”. Lastly, at the end of the film we hear that “there are no leaders but yourselves”. Although this class is about revolution, we always tend to relate revolutions around the worlds past with leaders. Leaders and leadership is a big part of revolution, and it’s a word that I think was left out of the board from the discussion of our very first class.

“This is all very disorganised”

I wasn’t quite sure what to expect going into Viva Zapata!, knowing it was both written by John Steinbeck – a figurehead of American socialism – and produced in the heyday of McCarthyism. Despite having now seen film, I still find it hard to ascribe it any kind of clear-cut ideological line. If anything, Viva Zapata! seems both desperate to say something relevant while trying not to come across as political in any way.

There is no question as to the film’s overwhelmingly sympathetic depiction of Emiliano Zapata. Portrayed as dashing and charismatic, his moral integrity is shown as unwavering throughout the Mexican Revolution. The Revolution itself is clearly a righteous cause according to the film, which depicts President Porfirio Diaz’s regime as corrupt and repressive, incapable of dealing out justice and actively destroying the livelihoods of the farmers in Morelos. However, the film is no less critical of the following regimes, and even under the presidency of Zapata himself, the government is inevitably unable to restore stolen lands to the impoverished Morelenses. None of the power structures established after an armed uprising are satisfactory, as they all seem to reproduce the same patterns of oppression as Diaz’s regime. This could almost be seen as a rejection of the concept of “rule from above”, which is seen as both inefficient and corruptible.

However, the own characters shown to be embracing such radical positions are Francisco Madero and Fernando Aguirre, neither of whom end up rejecting representative democracy when in power. Madero is initially presented as critical of the concept of representative democracy, as Aguirre quotes him as writing that “Elections are a farce, the people have no voice in government, control is in the hands of one man and those he has appointed”. While Zapata trusts him at first, as soon as Madero enters office he finds himself overwhelmed by the responsibilities of power, and refuses to change the institutions that were in place under Diaz. Worse, he fails to notice the coup general de la Huerta and his officers are plotting against him, despite their intentions being barely concealed. Madero thus comes across as naïve, blinded by his own idealism and almost comically bad at spotting his own enemies, and he ultimately fails to restore peace.

At first, Fernando Aguirre also seems ideologically driven, but his true intentions are only revealed towards the end of the film. He is presented as a radical intellectual working alongside Madero, although he quickly sides with Zapata when he sees the new president’s hold on power loosen. He also shows disdain towards the customs and general lack of organisation of Zapata’s followers, and seems unable to unable to understand the common people. As it turns out, all his actions were meticulously calculated to get him into a secure position of power, and he shows no second thoughts when ordering Zapata’s assassination. I can’t help but see him in particular as a critique of radical left-wing intellectualism, which Kazan and Steinbeck contrast with the agrarian simplicity of Zapata’s way of life.

Viva Zapata!

Elia Kazan’s Viva Zapata! tells us that the fundamental conflict at the heart of the Mexican Revolution concerns land. Indeed, “land and liberty” (tierra y libertad) has been the banner under which has historically erupted, in Mexico as in many other agrarian societies. But this is a conflict also between the countryside and the city, and between different temporalities. The film opens with a delegation of peasants, from the southern state of Morelos, disarming themselves as they enter the national palace in Mexico City to petition President Porfirio Díaz over a land dispute. By giving up their machetes they are also handing over their instruments of labour, but in any case they are already unable to work as the local landowners have used barbed wire to fence off the fields where they have historically harvested their crops. Díaz, paternalistically addressing them as his “children,” tries to fob them off by telling them to be patient, to verify their boundaries and settle things through the courts. “Believe me, these matters take time,” he tells them. All but one of the group is pacified by the president’s vague reassurances. “We make our tortillas our of corn, not patience,” he declares. “What is your name?” asks Díaz, riled up. “Emiliano Zapata,” comes the answer. Díaz circles the name on a piece of paper in front of him, and we have all the clues we need for the rest of the movie: Zapata is different, a man to watch, who will not bow down to authority.

Much later comes a scene in which the roles are reversed. We are in the same office, but Díaz has been overthrown and now it is Zapata who is, temporarily at least, in the position of the president, receiving petitions. In comes another delegation of men from Morelos, seeking to resolve a problem with their land. The complaint is against Zapata’s brother, who has taken over a hacienda whose lands had been redistributed. Now it is Zapata’s turn to prevaricate: “When I have time, I’ll look into it.” Again, however, there’s one man among the petitioning group who won’t put up with such delays: “These men haven’t got time,” he calls out. “The land can’t wait [. . .] and stomachs can’t wait either.” To which now it is Zapata who bellows: “What’s your name?” But on turning to a list similar to Díaz’s, about to circle the offending man’s name, he realizes the situation in which he has found himself, repeating the sins of the past. So Zapata, the true revolutionary, tears up the paper and angrily reclaims his gun and ammunition belt, to head back to Morelos with the men and sort out the problem straightaway.

Revolutions tend to repeat, the film suggests, but something always escapes. Towards the very end of the movie, as we suspect that Zapata is doomed, about to be swallowed up by the very revolution that he helped to start, Zapata’s wife, Josefa, asks him: “After all the fighting and the death, what has really changed?” To which Zapata responds: “They’ve changed. That’s how things really change: slowly, through people. They don’t need me any more.” “They have to be led,” Josefa says. “Yes, but by each other,” her husband replies. “A strong man makes a week people. Strong people don’t need a strong man.” This, however, is the basic tension around which the film revolves: it wants both to glorify (even romanticize) Zapata, and yet also to suggest that it’s the glorification of men like him that leads the revolution to fail. Indeed, Zapata is paradoxically glorified precisely in so far as he consistently refuses adulation. And so ultimately Zapata has to die, shot down in a hail of bullets, so that something of his spirit escapes, here (rather clumsily) portrayed through his white horse which is scene, as the closing credits roll, wild and free on a rocky crag.

Meanwhile, the more basic contradiction that this movie has to negotiate is that it sets out simultaneously to praise and to damn the very idea of revolution. The people’s cause is portrayed and eminently just, and it is clear that the normal political channels of protest or redress are blocked. What’s more, the film lauds Zapata’s instinct for direct action, his taking sides with the temporality of immediacy and against the endless procrastination imposed by bureaucracies of every stripe. (Surely something of this position-taking has to do with the medium itself: Hollywood always prefers men of action to bureaucrats, however much it is run by the latter rather than the former.) But we are not to take the obvious lessons from this portrayal. This movie was, after all, made at the height of the McCarthyite era, indeed in the same year that director Kazan himself would testify to the House Un-American Activities Committee–and, to lasting controversy, would sell out a number of actors and artists who he reported were (like him) former members of the Communist Party. Viva Zapata! had to be, as Kazan himself testified to the Committee, an “anti-Communist Picture.”

So we see how revolutions soon become morality plays, in which what is at stake is less their immediate impact than the lessons that others should or should not draw from them. Interpreting or representing the revolution soon becomes the site of a struggle that threatens to obscure the battles that the revolutionaries themselves fought. And sometimes the most effective counter-revolutionary narratives are the ones that claim to present the revolutionary cause with the most sympathy. Is it any wonder that John McCain, the former Republican candidate for the US Presidency, should tell us that Viva Zapata! is his favourite film? Or perhaps the point is that even the most counter-revolutionary representation has to acknowledge the attraction of armed revolt in the first place.