For information visualization software to be effectively employed in the classroom, it not only needs to address a particular topic, but it also needs to be accessible and engaging in order for students to make use of it. This is why software such as PhET is becoming so popular. The best types of learning are active, engaging, and inquiry-based. Not only does PhET allow opportunities for students to explore and visualize concepts, to manipulate variables, and collect data, it does so in an engaging, user-friendly and graphically enhanced manner, that is free and easily accessed. Many times students either work with theory or real labs but have trouble connecting the two. Simulations “scaffold students’ understanding, by focusing attention to relevant details”, (Finkelstein et al, 2005). At times, however, students miss the value of simulations and perceive them as “fake” (Srinivasan et al, 2006), wanting only “real experiments”. To avoid this problem, I would integrate simulations together with real labs and teacher directed learning so that they can appreciate the merits of the simulations while benefitting from their affordances.

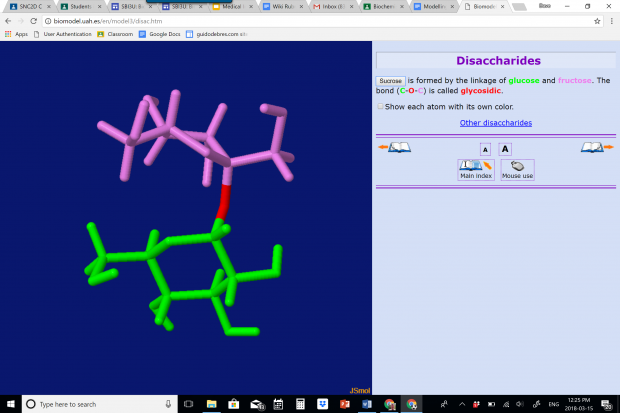

Previously, I wrote about using PhET for optics, but I will use it for chemistry as well. Many students struggle with chemistry, I believe, because they can’t visualize atoms, bonding or chemical reactions. It is very hard to conceptualize how atoms interact with each other when we can’t even see them. In my chem unit, I have students use molecular modelling kits to build simple molecules such as carbon dioxide, water and methane. They also use them to demonstrate reactions and balancing of equations. My students also perform various chemical reactions in “real” labs, but may have a hard time connecting these experiments with the molecular models, but see them in a separate way as single substances rather than being made of billions of atoms. Simulations can help to bridge this gap, allowing students to see how the molecules interact with each other to form new substances. Finkelstein et al (2005), write “properly designed simulations used in the right contexts can be more effective educational tools than real laboratory equipment”, as in this case, as students can visualize the process at the molecular level which would not be possible with lab equipment.

| Lesson Topic |

Methodology |

Desired Learning Outcome |

| Atoms & Ions |

Build an Atom PhET simulation |

Understanding of electron orbitals, valence shells, formation of ions; Game-based assessments |

| Molecules |

Molecular model kits, Build a Molecule PhET |

Understanding of how electrons move to form ionic molecules, or are shared to form covalent molecules |

| Chemical Reactions |

Lab experiments; teacher instruction; student made types of reactions brochure |

Various atoms and molecules can react in recognizable patterns to form new substances by rearranging atoms already present |

| Balancing Equations |

Balancing Chemical Equations PhET; practice problems; Level Up balancing game |

When substances react, matter cannot be created or destroyed, so any atoms present before must also be present after, just rearranged |

There are several PhET simulations I have or will integrate for use in this unit. I would use the Build an Atom simulation to assess their current understandings and to reinforce their understandings of an atom, its components, and how they relate to ions, bonding, and reactions. This simulation is ideally set up for inquiry learning and has assessment through four different games for engaging learners. I would then use molecular model kits to have them build simple molecules and to recognize how many bonds each atom is capable of forming, so that each valence shell is filled. After having the students perform experiments of various chemical reactions and make a brochure about the different reaction types, I would have them explore the Balancing Equations PhET.

What makes this simulation so effective is the visualization of the molecules as they balance, an immediate feedback mechanism that says if they are correct, or what the problem is, and a game with various levels to increase difficulty of the problems as they grow in understanding. This PhET meets the standards of effective use by Stieff and Wilensky, (2003), who seek “multiple representations of concepts at multiple levels, guided exploration with immediate feedback”. I have also created a paper game I call “Level Up” that I use in my class as well for balancing equations in a self-directed way with teacher feedback. Using a blended approach will allow students to move away from rote memorization and repeated practice to develop conceptual approaches to problem solving while using feedback-based reasonings to justify their answers (Stieff & Wilensky, 2003). Finally, the use of game-play and leveling up offers intrinsic rewards and incentives to motivate students to get to the next level and build on their understandings. It has a social aspect as well, as students can assist each other in working with the simulations, work together to support understandings, or engage in friendly competition to see who can level up the fastest.

Discussion:

- Students sometimes perceive simulations as “fake”. How can we help students appreciate the value of simulations for visualizing concepts?

- How should simulations be scaffolded to maximize their effectiveness?

- Digital resources often serve to isolate if students work independently. How can simulations be used effectively within a learning community?

- Finkelstein, N.D., Perkins, K.K., Adams, W., Kohl, P., & Podolefsky, N. (2005). When learning about the real world is better done virtually: A study of substituting computer simulations for laboratory equipment. Physics Education Research,1(1), 1-8. Retrieved April 02, 2012, from: http://phet.colorado.edu/web-pages/research.html.

- Srinivasan, S., Perez, L. C., Palmer,R., Brooks,D., Wilson,K., & Fowler. D. (2006). Reality versus simulation. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 15(2), 137-141.

- Stieff, M., & Wilensky, U. (2003). Connected chemistry – Incorporating interactive simulations into the chemistry classroom. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 12(3), 285-302.