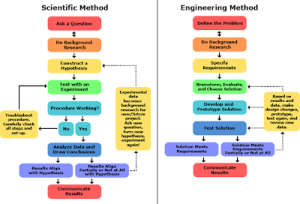

This week, the two most interesting articles I read were Mirror Worlds and Deepening students’ scientific inquiry skills during a science museum field trip. While I found some elements of the field trips article problematic because it took for granted that teachers were too overworked to fully plan for a field trip to a museum that would meet their curricular outcomes, I found its focus on developing inquiry while on site interesting. In my personal experience, field trips are carefully planned with pre-visits to the site. The site is then used to seek answers previously asked or to spark inquiry that will be brought back into the classroom for later learning. In this article, Gutwill focuses on teaching students skills for inquiry through a shift from scientific knowing to scientific questioning.

Gautam, on the other hand, focused on “mirror worlds” in which the entire field trip is virtual and learners meet and collaborate with others in an online environment without ever leaving the classroom. Immersive education provides learners with the feeling of “being there” even when physical presence is not possible (Gautam, 2018) and there is a digital representation of real-world objects. This version of embodied instruction provides an exciting possibility, as described by Gautam et. al. because it allows users to collaborate in a common environment via remote locations, represented as avatars. It opens up possibilities for rich socio-cognitive learning amongst peers without expense and hassle of traveling to onsite learning environment.

For me, the learning this week was in separating embodied learning from situated learning. Situated cognition, Gautam writes, is best achieved when knowledge is situated in authentic contexts. The focus being on developing learning that is useful and not learning for the sake of learning. For the learning to be effective in this instance, the learner must feel present in the environment in order to construct their understanding. For this to happen there must be immediacy (synchronous interactions) and intimacy (ability to interact with others via proximity, eye-contact, etc.). This leads me to question the difference in cognitive benefits between learning onsite and learning via virtual environments. I would welcome your thoughts and further readings.

- What do you think is the impact of “virtual field trips” for students who may already be disconnected from their immediate environment? If students are able to experience in-situ experiences in exotic places but are not familiar with what is around them, how does this impact their understanding?

- I had a conversation this week with a colleague regarding a project for the upcoming year that I would distinctly categorize as inquiry due to the open-ended nature of it and the fact that we are beginning with a question. The colleague, however, cautioned that we should not call it inquiry when introducing it to the staff because inquiry had such negative connotations, which shocked me a little. In your context, how is inquiry a used for your learners to understand learning contexts both on virtual and lived field trips?

- How might you tweak a lesson you have recently taught in maths or sciences to integrate embodied learning?

Gautam, A., Williams, D., Terry, K., Robinson, K., & Newbill, P. (2018). Mirror worlds: Examining the affordances of a next generation immersive learning environment. New York: Springer

Gutwill, J. P., & Allen, S. (2011). Deepening students’ scientific inquiry skills during a science museum field trip. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 21(1), 130-181.