As I was reading the instructions for this post I decided to remix one of my earlier ideas (which I had posted so late passed the deadline I missed the chance at peer interaction) because it fit so well into this assignment (and I was proud of it and wanted it to have another chance at generating conversation!) 😉

I chose to focus on the TGEM framework and utilized a PhET applet. The misconception I selected was that of buoyancy and its relationship with gravity/mass/density. As I pointed out in the first iteration: In Grade 3, students in Ontario study material forces. I recall classes having a hard time understanding why the buoyant force allowed certain objects to seemingly overcome the force of gravity but not others. The concepts of mass, volume, and density are not solidified at this stage so explanations or even demonstrations were not usually deeply understood. There are several buoyancy simulations available online but I feel the PhET one described below is the most useful. As Finkelstein et al. (2005) mention PhET simulations “are designed to be highly interactive, engaging, and…provide animated feedback to the user. The simulations model physically accurate, highly visual, dynamic representations of physics principles” (p.2). Furthermore, this particular Info-Vis simulations also provides a ready-made set of data (which I considered “large” for the purposes of primary education) required within the GEM framework that the students could refer back to as they gained deeper understanding of what they were looking at (Khan, 2007).

If I had an opportunity to teach this Science unit again using T-GEM cycles and Info-Vis applets the lesson activities might look something like this (over a series of classes, I’m sure)…

Buoyancy & Mass Lessons ala TGEM & PhET

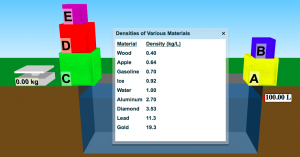

Step 1: Compile Information – I would begin with showing students a data table for five blocks of mystery objects from the PhEt Density & Buoyancy Simulation and demonstrating how to read a two-column chart. Then we would briefly discuss what students know about these objects, the abbreviations (what does L and kg stand for?) and the numbers beside them (making a connection to money when reading decimals, are these numbers placed in any particular order?). Add keywords to a word wall: litres (L), kilograms (kg).

Source: https://phet.colorado.edu/sims/density-and-buoyancy/density_en.html

Step 2: GEM Cycle 1

Generate – Then, I would begin by asking students to find trends or generate some relationship statements about the data in groups and share with the class. For example, “The water has the smallest number but the gold has the largest number” or “I wonder why gasoline is smaller than water? Aren’t they both liquids?” Other questions related to the nature of the data the teacher might guide discussions of include: “What might ‘density’ be measuring?”, “Why is the pool measured as 100 L but the scale measuring 0 kg right now?”

Then, I would direct their attention to the cubes and ask them to explain what they see: Each shape is a cube, they’re five different sizes, five different colours, labelled with five different letters. I would ask them to put the cubes in order in two ways (letter label and size) and then to predict what the scale would read if I were to measure each cube. (I would deliberately not use the term “weigh” or introduce the term “mass” at this point). I would also ask them to predict whether they think any of the numbers on the data table might appear on the kg scale and whether/how the 100 L measurement of the pool might change.

Then, I would ask students to predict which cube would measure the highest number when I place it on the kilogram scale. (They will likely say the largest cube will be highest and smallest lowest and I will add the word “size” to our word wall). I would ask them to write a rule explaining what they think the relationship between a cube’s size and its kilogram measurement.

Evaluate – Now, I would begin the simulation by placing each cube on the scale and have a student scribe for the class to record the data in a new table:

| Block Label | Size (1-5, 5=largest) | KiloGrams (kg) |

I’m deliberately constraining them at this point by doing this part of the simulation as a demonstration to keep them from dropping the blocks into the pool or changing any of the other variables. I’d ask them to reflect on what they saw: Were your predictions completely correct? How can you explain this? I’d ask them to notice the L measurement change and compare that by measuring the block on the kg scale again and compare these numbers…

Modify – Finally, I’d ask the students if their original rule needs to be changed now that they’ve seen the measurements. Then I’d have their groups try to make a new rule explaining why each block received the measurement it did since now they see that it can’t be because of its size.

Step 3: GEM Cycle 2

Generate – To start the second cycle, I would ask students to predict what will happen when each block is dropped into the pool and explain their thinking. If they say the same thing will happen to all five blocks (ie. all sink or all float) I would not correct that at this point. I would ask them to draw what would happen on a two-column drawing one side for “prediction” the other for “actual”. I’d again ask them in their groups to write a “rule” for predicting what will happen to a block when it’s dropped into a pool of water.

Evaluate – Now, the students would stay in their groups and load the simulation themselves using the Mystery button and experimenting with dropping the blocks into the water, and drawing what actually happened beside their predictions. I’d ask them to reflect on what they saw: Were your predictions completely correct? How can you explain this?

Modify – I’d again ask the students if this original rule needs to be changed now that they’ve run the simulation and have their groups try to make a new rule explaining why each block behaved as it did when dropped into the pool and write that down. I’d ask them to record the kg of each block on the “actual” side of their diagrams and consider whether this number might be connected to what they observed in the simulation or not when they make their new rule…?

Step 4: GEM Cycle 3

Generate – At this point, I would ask students to predict what will happen when each block is dropped into the pool if the simulation is changed so that all blocks have at least one thing the same, if they all measured the same kilograms for example. I’d again ask them in their groups to write three “rules” for predicting what will happen to the blocks that are all the same (a) mass, (b) volume, and (c) density when they’re dropped into a pool of water (it’s not important that they don’t know what these terms mean, this is part of the discovery).

Evaluate – Then, the students would stay in their groups and load the simulation themselves and use the “same” x buttons to set the blocks to the same value and continue experimenting with dropping the blocks into the water. I’d ask them to reflect on what they saw and evaluate their predicted rules. I’d assign a role to one of the group members to keep a running record of “things we want to know/don’t understand” and to another as the recorder to write or draw the group predictions and rules and the actual results. At the conclusion of this part of the simulations, I’d ask them to come up with a working definition of the terms “mass”, “volume”, and density” that they’ve been observing.

Modify – I’d again ask the students if their original rules needed to be changed now that they’ve run the simulations and have their groups try to make new rules explaining why each block behaved as it did. I’d challenge them to incorporate their definitions of “mass” and “density” into their explanations.

Step 5: GEM Cycle 4

Generate – Finally, I would ask students to think about four materials that come in blocks they are familiar with: Ice, Metal, Wood, and Styrofoam. I would ask them to explain to me what would happen if I threw a block with the same mass but of each different material into the pool. (I might bring in these objects and a bowl or aquarium to help them imagine). I would then return to the Mystery simulation screen and reveal to them that the blocks in this simulation are each made of a different mystery material just like my example objects. I would ask them to generate a rule using material names for what would happen when we dropped those materials into a pool.

Evaluate – So now, the students would stay in their groups and load the simulation but go to the Custom button. I’d ask them to experiment with the different materials, their masses and volumes and explore/record/discuss what happens.

Modify – I’d ask the groups to use this information to try to identify the material of each mystery block using the data from all the simulation tabs. As an extension, I’d introduce the Buoyancy Simulation (Intro tab only) and allow them to gather information to inform their hypothesis from those materials and we’d discuss the concept of weight (N) versus mass (kg) at this point, while formally introducing the topic of the buoyant force. Finally, we’d return to the data table from the first cycle and ask students to explain what it means that wood has a density of 0.40 kg/L while lead and gold (both metals) have a much higher density. What would happen when we drop wood into the pool versus metal? Then in the Buoyancy Playground tab of that simulation, they’d compare materials such as styrofoam, wood, or metal and craft two final truth statements (1) about gravity (N or kg) and density, (2) about density and buoyancy.

Step 6: Consolidation and Extension/Next Steps

I’d ask the groups to tweak their truth statements until they feel ready to share them with other groups, then write them on a chart paper, leaving the marker there, and go do a gallery walk to see what other groups decided. Viewers can record their affirmative or contradictory ideas and questions underneath the truth statements, from “Yes, we agree” to “What about … ?” or “But x doesn’t y so how do you explain that?” Groups would then come back together to read and reflect on the feedback, going back into the visualizations and revising their ideas as necessary. I’d have them hand in a paper copy of their two finalized statements for formative assessment.

Finally, I’d draw their attention to the bottom of both tabs in the Buoyancy Simulations where the density of the fluid within the pool can be changed and observe what happens to the blocks when the fluid is converted to “air” “gasoline” “olive oil” “water” or “honey”. A conversation about viscosity is beyond the Grade 3 curriculum but students with Gifted designations would still be able to grasp that, if not the rest of the students, especially when presented using this format.

Synthesis

Finkelstein et al. (2005) points out that “it is possible, and in the right conditions preferable, to substitute virtual equipment for real laboratory equipment” (p.6) and in this circumstance I completely agree. In the past, I have attempted to teach concepts of mass, density and the buoyant force using an actual aquarium filled with water and a variety of real objects. There was not enough equipment to go around, a lot of watching the pushier kids do it, a lot of mess to clean up, noise to contain (I teach in an open concept building where this is an issue) and frankly, very little real learning other than comments about “how cool” that was. This simulation, particularly planned using the TGEM framework, would have accomplished real learning goals in a much more satisfying, comprehensive, and inclusive manner. Combining the TGEM framework with PhET also addresses the issue Yeo et al. (in Finkelstein, 2005) noted that timely “reflective points” should be provided to ensure students can’t just “exit a screen with alternative concepts left intact” (p.6).

It’s interesting to note the findings of Srinivassan et al. (2006) that students learning via a simulation “don’t have a sense of partaking in what they perceive as authentic experience[s]. They seem to need/want authenticity to be able to make the connections the experts make with the simulations” [i.e. that the results of the simulation are the same as if they are using “real” items] (p.140). I wonder if my students would feel the same way? Would they be able to transfer their truth statements from the simulations above to real life problems, accurately predicting where a cube of a particular material would float in a real aquarium for example?

Admittedly, such lessons, even without the extensions, would take quite a bit of class time to navigate successfully and that is always a serious drawback in the real world of teaching. Nevertheless, when it comes to applying this to my (previous) practice, visualizing information, and applying a learning framework specifically to address a misconception, I believe it would extremely effective compared to what I’ve done in the past. Who knows, I might even see if the Grade 3 teacher would like to collaborate and run this lesson during our Library/Tech periods! 😉

Discussion

- Have you taught these concepts in a different way or to a different age group? Are you familiar with some of the other buoyancy-esque online tools, such as BBCs InfoBits or YouTube videos, and how do you think they compare?

- Do you think there’s a way to accomplish the learning goal while keeping the TGEM and Info-Vis lesson models without sacrificing so much class time?

- What about summative assessment? In my opinion, it feels wrong to assess knowledge gained using simulations, visualizations, and the scientific equivalent of what Sinclair and Bruce (2015) refer to as virtual manipulatives with a pencil and paper activity/test. Can you suggest a more integrous way to assess student learning at the conclusion of this?

References

Finkelstein, N.D., Perkins, K.K., Adams, W., Kohl, P., & Podolefsky, N. (2005). When learning about the real world is better done virtually: A study of substituting computer simulations for laboratory equipment. Physics Education Research,1(1), 1-8.

Khan, S. (2007). Model-based inquiries in chemistry. Science Education, 91(6), 877-905.

Sinclair, N., & Bruce, C. D. (2015). New opportunities in geometry education at the primary school. ZDM, 47(3), 319-329.

Srinivasan, S., Perez, L. C., Palmer,R., Brooks,D., Wilson,K., & Fowler. D. (2006). Reality versus simulation. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 15(2), 137-141.