A recent transplant to New Westminster, Betty Gray moved to British Columbia to get away from the cold winters of Alberta, where she has lived for most of her life.

Betty was born in 1950 in Lethbridge. She lived her early years in Barons, a small town in southern Alberta. “It was the prairies. I remember it being flat. You could see for miles and miles,” she laughs.

Her father was a farmer and she had a good childhood growing up, running around the fields there, swimming in the lake. She formed a close bond with her sister Helen and cousin Judy, especially since all of the other cousins in the family were about ten years older. “When we went to family reunions, we were always the youngest of the cousins.”

Her mother’s passing when Betty was 11 meant Betty had to grow up quickly. She taught herself how to cook, clean, and essentially become the primary homemaker.

She graduated high school (she liked history and economics; her nemesis was typing class) and then went to hairdressing school, but she soon realized she wasn’t suited to hairdressing and moved on to a variety of jobs: waitress, chamber maid, sales clerk, cook. Her life and career wouldn’t get definition until going through a life-changing experience in Elk Point in 1980.

1980 was Alberta’s 75th anniversary of the province joining Confederation, and there were homecoming community projects all over the province.

“It was almost Biblical,” said Betty. Like how Joseph and Mary and the rest of them had to return to their hometown to register for taxes, everyone in Alberta was returning to where they were born for Homecoming.

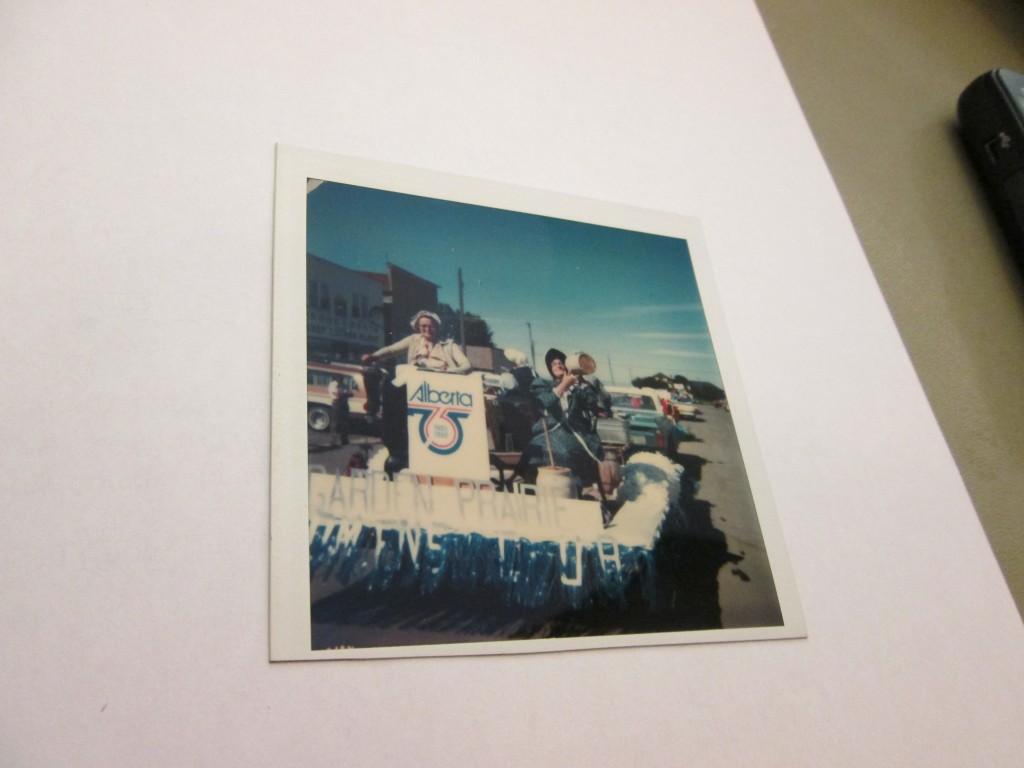

Everyone went back to their hometowns to celebrate Alberta’s 75th. Betty took this photo at the Barons homecoming celebration.

It was Alberta’s 75th birthday. Sheet cakes with the same 75th Anniversary logo were a staple at the different community Homecoming celebrations.

At that time, she and her husband and daughter were living in Elk Point. Betty was writing for the local newspaper and working at a liquor store.

One of Betty’s assignment was to go to the Homecoming 1980 Committee meeting. She was only there taking notes for the article she was writing but since she was the only writing everything down, her notes became the first meeting minutes, and Betty was asked to serve as the committee secretary.

Some of these pins were given to Betty to thank her for her work on the Elk Point Homecoming Committee.

Betty can still remember the details of learning how to be a club secretary, expanding her skills in public relations and taking on more and more responsibilities, as she later took on the position of committee treasurer too. It gave her a taste of the work that she could be doing, meaningful work that she had the potential for.

“I realized I’m not dumb. I can do more.” Betty doesn’t fully recall where her low expectations originated: maybe it was because she didn’t have her mother during her formative years, or maybe because she settled into the comforts and familiarity of being a wife and mother, but joining the Elk Point Homecoming Committee changed all that.

“Those years in Elk Point were watershed years for me…where I ‘found myself.’” Betty was liberated when she realized didn’t have to wait for her husband to make her happy and that she wasn’t responsible for her daughter’s happiness either.

“I was just taking notes at a meeting and it changed my life forever.”

With her newfound confidence and skills, Betty eventually landed her favourite job. “The elusive ‘dream job’ of all time,” she says. It was running a health promotion program called Action for Health, implementing population health strategies at the community level. As a self-professed workhorse, she relished the hands-on nature of her responsibilities there. Then came a structural reorganization that closed down the program.

It was a blow to Betty to not be able to see the fruits of her labour. “We were doing something good and worthwhile. I would have liked to see what we might have accomplished had we been allowed to continue.”

Losing her dream job was hard for Betty, but if she were to give advice to her past-self, she would tell herself that nothing matters.

Nothing matters, she says, not as a discouragement, but as a liberating reminder to avoid wasting time worrying about perfection and other people’s expectations.

“I know there are file boxes back in Smoky Lake filled with all the work that I did for Action for Health. Boxes and boxes of stuff that no one has bothered to go through…that nobody cares about anymore.”

Her dream job is now just a cherished memory, but that’s okay, Betty says.

“[You] do it because it matters to you.”