Early life in Prince Rupert

Margaret Lee was born in Vancouver and grew up in Prince Rupert during the 1930s. From an early age, she busied herself with school while helping out in her family’s confectionary store.

Outside of school and the family business, Margaret went to church and during her teenage years, was part of the Canadian Girls In Training (CGIT) similar to the Girl Guides of today. In the pre-WWII era, she was involved in the Chinese Youth group that petitioned the Canadian government to stop sending scrap metals to Japan during the Japanese invasion of China. Her diverse group of friends that included a Scottish, English, Japanese, and Yugoslavian girl was dubbed the “United Nations.”

Margaret grew up during the Great Depression and remembers how much hardship the family store faced. “If we made $5 a day, it was considered a good day,” reminisces Margaret, as she recalls the period when there was very little food, no social security, nor jobs.

WWII and the boom after

In her late teens, Margaret felt the effects of WWII. In Prince Rupert resources were very limited and food was rationed. Margaret remembers there being “black outs” during the night when the entire neighbourhood lined their windows with dark curtains to minimize outdoor light to prevent enemy aircrafts from targeting the town.

After the war, Prince Rupert boomed. Margaret landed her first job working in payroll at a plant building project in Port Edward. The Chinese Canadian men who had volunteered to go overseas to fight in the war started coming back, and amongst them, Margaret met her future husband.

A “life-changing” marriage and military life

In 1950, 25 year old Margaret married an army man, Dan Shiu in Vancouver. From then on, her life took a drastic turn as she went to live in an army camp. Margaret and her family lived in the Vancouver Wireless Station army camp in Ladner (currently Boundary Bay Airport) from 1950-1968. They would later be sent across Canada to Ottawa, Inuvik (NWT) and Masset (Queen Charlotte Islands, now Haida Gwaii).

Margaret’s daughter Martha remembers life being very structured and the community being very close-knit. Vancouver Wireless was a 24-hour station which meant someone was always on duty. The children had to play quietly in the daytime since they never knew which of their neighbours were sleeping in preparation for their graveyard shift.

Aside from having to move wherever her husband was stationed, Margaret also had to spend time on her own with her 3 children when her husband was sent away on courses. When he was gone for 6 month assignments to Alert, the most northern station on Ellesmere Island, vocal communication with her husband was extremely limited and could only be done through a HAM radio. She vividly remembers one particular year, as a young mother, when all 3 of her children became ill with chicken pox at the same time and she miraculously survived through it alone and nursed them back to health.

The military base in Ladner was quite self-sustainable, with its own school, church, fire-hall and a store with basic necessities. The people formed a close community. The camp was surrounded with barbed wire fencing and had a guardhouse where visitors had to sign in before entering. “It’s not like we were in a prison,” says Margaret, and Martha adds, “It’s not like we couldn’t get out. It’s just that not everyone could get in.”

Once a month, an army bus took the women from VWS to New Westminster to shop at the “Golden Mile” (Columbia Street) and the Woodwards department store. There were also bus runs in the morning and afternoon for people to go grocery shopping in Ladner.

At home, the Shiu family ate Chinese food and bought fresh fish from Mr. Ho, whose truck was allowed into the military station once a week. Despite their racial and cultural difference, the family was well-integrated within the community. “We were very lucky to have met such good people and friends in that camp,” recalls Margaret. “I only realized I was Chinese in university,” laughs Martha. Whenever they moved to a different posting, the Shiu family always met another family they knew from another camp, which made it easier for them to adapt to their new homes – even as far north as Inuvik.

Life in Inuvik in the late 60s

When Margaret’s husband was transferred to Canadian Forces Station Inuvik in the late 60s, there were many newcomers arriving in the native town. They were the only Chinese there amongst a mix of Indians, Eskimos, government, armed forces and oil and gas exploration people. However, within such a small community, any initial tension was eliminated as people got to know them on a personal level. Margaret interacted with the natives working as a substitute teacher and later, as a receptionist at the town’s hospital. Dan and the children took part in many community activities and joined badminton, curling, table tennis, darts, baseball and hockey teams.

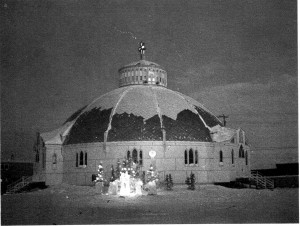

According to Margaret, her children “hated” living in Inuvik during the first weeks of arrival in the summer. Martha describes the town as an isolated, dusty place with swarms of black flies and nothing pretty in the summer time, but beautiful during the winter. She recalls how the -30 degree average weather brought activities like skidoo-riding and skiing, as well as magnificent ice sculptures outside Inuvik’s Our Lady of Victory Church (also known as the Igloo Church). The most difficult adjustment to living in the North was the isolation and the 6 months of daylight and 6 months of darkness.

A disappearing history – The Ladner military station and Chinese heritage in New Westminster

Margaret has gone back to visit the military station, which is now the Boundary Bay Airport. In place of all the houses, school, church, and community space that previously filled the site, there are, at least, plaques to mark the history. However, Margaret laments the fact that fewer and fewer people know that there ever was a military station there. The history of Ladner military station may soon be eradicated by modern land developments and infrastructures. The same can be said about the Chinese-Canadian history in New Westminster.

Margaret and her family moved to New Westminster in the 70s and since then, notes the significant increase of high-rise buildings and demolition of older heritage sites being replaced by new malls, parks, and structures that appear out of place in the city.

In spite of their lifestyle, moving from one military station to another, Margaret and Martha always maintained a sense of their Chinese-Canadian identity. Naturally, they still feel strongly about the Chinese-Canadian community in New Westminster and the heritage buildings, all of which have been destroyed by consecutive fires or replaced by new developments. Both of them are actively working to preserve the Chinese-Canadian history by participating in activities like this documenting project, and calling attention to the importance of heritage sites and the prevention of their continuous demolition.

When asked what she would tell her 20-year old self, Margaret immediately says, “learn how to drive.”

My name is Elizabeth Chinnick my Dad was Al Rodominski and he served at Vsw and we lived in a duplex my Dad is no longer with us. My mom is 91 her name is Dot.