This week’s post is a continuation of what I had talked about in my last post. After reading a Chapter out of Judith Butler’s book “Frame of War: When is life Grievable,” I found information that I believe supports what I

was previously trying to articulate.

I had previously expressed how I was bothered by how, following the attacks on September 11th, we indirectly placed value on certain lives and not others. I found that Butler communicates what I was trying to say really well when she proclaims that “We […] think of war as dividing populations into those who are grievable and those who are not. An ungrievable life is one that cannot be mourned because it has never lived, that is, it has never counted as a life at all,” (Butler 38). She continues by acknowledging the immense public grieving dedicated to US nationals in comparison to the lack of “public grieving for non-US nationals, and none at all for illegal workers,” (Butler 38).

I’ve come to realize that people don’t always like to look at the whole story, we see parts of it and accept that as the truth. I think it’s important to consider Butler’s argument when reflecting upon 9/11. Although Butler only addresses illegal immigrants and non US-nationals in the passage stated above, her statement still applies to how we think about those in the Middle East, and other foreign war torn countries. During times of war, we tend to pick sides, and by default, we often dehumanize “the enemy”. This is demonstrated in how we choose who is commem

orated and who is not, who we choose to remember and who we justify as a “consequence of war”.

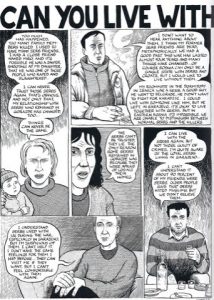

This idea of dehumanization is present in many of the books we have read in our ASTU class, such as Obasan, Safe Area Gorazde, and The Reluctant Fundamentalist. However, I felt that it was the most prevalent in Safe Area Gorazde by Joe Sacco. The journalistic comic book describes the authors time in Bosnia from 1994 – 1995, following the Bosnian war. The book consists of Sacco’s personal experiences and conversations with Bosnians about their time during the war. There was one chapter titled “Can You Live with Serbs Again,” where a handful of Bosnians answer th

at very question. In many of their answers, they dehumanize and villainize Serbians because of the acts that have been committed in the name of war. Although it can be justified, we can see how Safe Area Gorazde advocates Butler’s argument that in times of there is an evident divide. Through Sacco’s lens, the lives of the Bosnians were put at the forefront of the novel, it was their lives that were commemorated, rather than the Serbian lives lost, who were “the bad guys”.

It is important to consider Judith Butler’s ideas when analyzing times of war. We can see in both the events of 9/11 and the Bosnian War that the side you are on determines whether or not you will commemorated.