Hello readers!

In my ASTU 100A class this week, we were lucky enough to visit Joy Kogawa’s archive collection (as mentioned in my previous blog post, she is the author of Obasan) in the Rare Books and Special Collection area in UBC’s Irving K. Barber Learning Centre. Before moving on to some of things that are present in this collection, I feel as though I need to identify what an archive collection is, as I myself had little knowledge about this subject prior to this “field trip”.

According to the woman supervising our visit, archives can be defined as documents that are created or received by a person or organization. Such documents are essential to these peoples’ every day lives; examples may include diary entries and letters. Archives are especially important to scholars because they act as primary sources, or first-hand accounts, without outside analysis. These documents are organized by the person/ creator in contrast to libraries, where they are organized by subject. In other words, archival collections follow the principle of provenance — the bringing together of documents naturally in the original order of creation. With regards to archival organization, Kogawa’s collection of archives is referred to as a “Fonds”, which involves various paperwork, versus a “collection”, which deals with objects.

Moving on to Joy Kogawa’s Fonds specifically, it was really inspiring to see the amount of effort it took for her to write Obasan. As a student, I am constantly exposed to various types of scholarly articles, books, etc., as well as the graphic narratives and novels that I have mentioned in previous posts with regards to ASTU. In any case, every scholar appears incredibly intelligent; I cannot picture them writing anything that resembles a terrible first draft. This mindset also applies to Obasan; I could not visualize the piles and piles of drafts that Kogawa went through before even sending the novel to an editor in the hopes of it being published. However, my experience at her Fonds changed this mindset. Somehow, Joy Kogawa — the greatly revered Japanese-Canadian novelist — became a real person.

I witnessed scrap pieces of paper, in the form of an invoice and the outside of an opened envelope, with character analyses scrawled across it. There were drafts upon drafts of the novel present, with various changes written throughout by Kogawa and a variety of editors. I skimmed through an old catalogue, where the first version of Obasan appeared, with a pink and white cloth cover and lengthy quote encompassing the front of the novel.

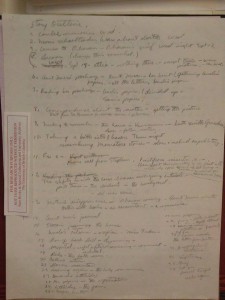

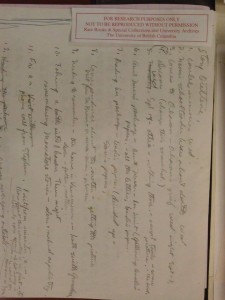

Out of everything that I saw, the most exciting archive was a potential story outline for Obasan. Reading through this document gave me insight into Kogawa’s thought process. It was while looking through this outline that it hit me: Kogawa had to go through the same process that students do when writing papers in order to create this novel. She probably had her doubts about what she was writing and whether or not it was going to turn out in the end. On the outline, she moved some events around and crossed potential ideas out, as you can see in the photos below. She wrote them in messy handwriting that is only legible if you look closely at it. Ultimately, this outline sums up her struggle to figure out how to organize her thoughts into one cohesive body and tell the story she wanted.

This idea that Kogawa is a regular person has changed my entire perspective of the novel, as I have much more appreciation for her attempt to make known the tragic events experienced by Japanese-Canadians during World War II. I respect the order in which the main character, Naomi Nakane, remembers her family’s history and personal tragedies because I have now witnessed the effort it took for the novel’s storyline to end up where it did. As as student, I can somewhat empathize with Kogawa’s struggle to create this novel and have a better idea of where she was coming from when she wrote it. In other words, the ideas regarding Obasan did not magically pop into her head when she was writing; the hard work that Kogawa put in to produce this novel is evident in her Fonds.

Readers, if you ever get a chance to experience this unique collection, I highly recommend it!

Until next time!

Works Cited

Kogawa, Joy. Catalogue. n.d. Box 12 File 3. Joy Kogawa fonds. University of British Columbia Library Rare Books and Special Collections, Vancouver, Canada.

Kogawa, Joy. Draft of Obasan. n.d. Box 11 File 4. Joy Kogawa fonds. University of British Columbia Library Rare Books and Special Collections, Vancouver, Canada.

Kogawa, Joy. Story outline of Obasan. n.d. Box 8 File 11. Joy Kogawa fonds. University of British Columbia Library Rare Books and Special Collections, Vancouver, Canada.