Tips and examples submitted by TAs, compiled and edited by former TA Coordinators Yilin Wang and Sasha Singer-Wilson.

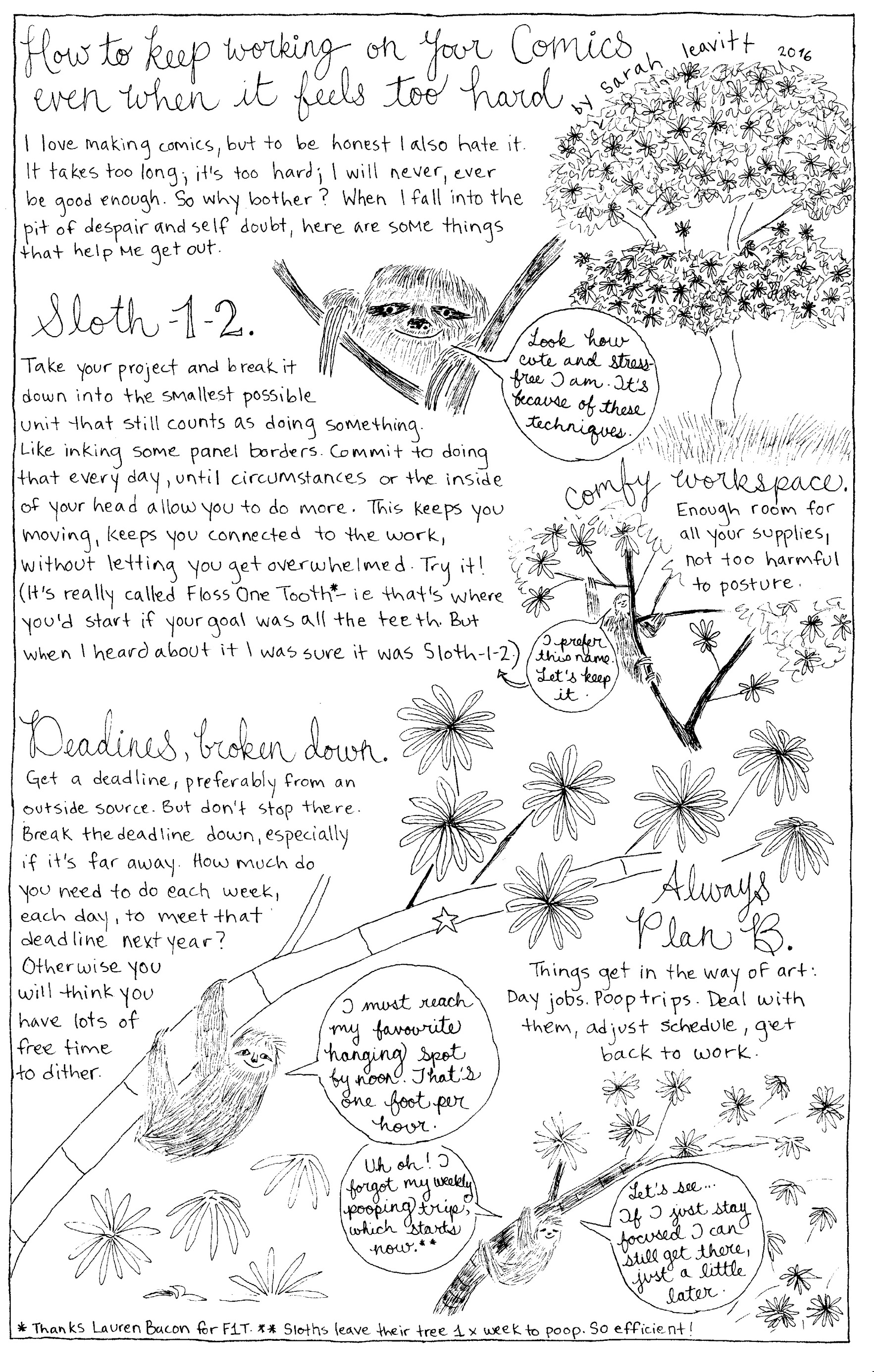

Ways to save time

Starting to grade:

- Familiarize yourself with the assignment criteria, rubric, and the goal of the assignment before you start.

- It’s helpful to know what the GPA goal is for each assignment before marking and also helpful to find ways to ensure consistency with other TAs.

- Go through a bunch of assignments and read them to see what level the class is at before starting to grade.

- Grade together with other TAs or ask for feedback from the instructor on the grades for a few assignments before you grade all of them.

Writing comments:

- Use a feedback bank.

- Create your own feedback bank for the assignment, allowing you to reuse common comments from the past.

- Write your comments in a separate document and save them before you paste them into Canvas.

Keep track of time:

- Use timers when you grade (one for the total time you are going to spend grading, and one for slightly less than the time you want to spend per assignment, so you can wrap up and move on) (Pomodoro timer: https://tomato-timer.com/ and others online).

General tips:

- Stay away from distractions.

- Spread it out (try to do 5-10 a day rather than many in a day).

Feedback tips for all genres

- Start and end with positive feedback.

- Keep in mind that it might be their first attempt.

- Identify ways in which they can improve their grade for subsequent assignments.

- Be specific with constructive feedback.

- Reference the rubric.

- Recommend resources (e.g. Writing Centre, Purdue Writing Centre: https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/, etc.).

Some go-to positives: - You’ve created a great sense of atmosphere here…

- This story packs great emotional impact…

- I love the sense of place in this piece…

- What an exciting story. I couldn’t predict the twists and turns – not always easy to do!

- The characters in this story feel well-rounded and dynamic.

- I particularly enjoyed the scene in which______

- Beautiful language! (Talk about a great section or phrase.)

- A good place to start for fiction/non-fiction: this is an interesting story about _____, with themes of ______ and _____.

Some go-to constructive criticism: - Adding more concrete imagery will help anchor the reader in the setting more clearly (applicable to almost any genre!).

- It’s great that your poem/story/song is hitting on some universal themes, and how might you reshape the story so that it feels totally fresh and unlike anything we’ve ever heard?

- Specific character- or setting-related details can really help bring a piece to life. Imagine yourself in the world of your character: what do you see, hear, feel? How is it different from what someone else might see, hear, or feel? Consider what will make your reader say, “Ooh, I’ve never heard that before.”

- The character’s motivations for doing ____ are a little unclear. Could you illuminate their mental landscape in this scene a bit more clearly?

Closing comments/encouraging nuggets:

- Keep going!

- Excellent work!

- Well done!

- Good effort!

- Good improvement.

- Look forward to reading your next assignment.

- Fascinating!

- There’s so much potential here!

- Thank you so much for sharing this!

- Soar ever onward through the skies of literary success!

One more thing to note:

If you come across a submission with very difficult subject matter, immediately stop reading and contact the instructor.

Tips for grading Fiction

Common issues:

1. The story, particularly the theme, is too explicit. New fiction writers tend towards the profound in their character’s internal dialogue, all the while forgetting necessary elements of scene, plot, and dialogue.

When this happens, you may urge them to develop more of a sense of place, using other characters and dialogue to get their point across more implicitly. Really what it boils down to is: show don’t tell.

2. The story all happens in the last 90% of the submission. Four pages of nothing, and then WHAM, someone dies and the real story kicks in.

In these instances, remind writers of the importance of editing; most writers struggle with ‘writing in’ to a piece, and come to their actual kernel after quite a few pages. There’s nothing wrong with that in the initial writing process. However, that’s the benefit of leaving sufficient time to edit; you have time to both ‘find the story’ and calibrate the rest accordingly.

3. The story goes off on irrelevant tangents.

When this occurs, quote specific lines or instances in the stories and then ask whether they’re essential or not.

You might also encourage them to see what it is their character wants and consider whether they get it. This sometimes helps eradicate extraneous material.

Constructive comments:

- “More firm application of the creative writing principle ‘Show, Don’t Tell’ would strengthen this piece.”

- “This character feels well-rounded, and it would be great to see the other characters developed more as well.”

- “I advise you to review your use of point-of-view in this story. Look for places in which you’re slipping out of point-of-view and remember that the voice/language should be appropriate for the viewpoint character.”

- “Please review the difference between scene and summary and consider when it’s better to use one form or the other.”

Tips for grading Children’s and YA

What to look for:

- Children/YA protagonist should be the active character, fixing their own problems (not relying on adults).

- Picture books:

– No redundancy in words and images

– Use of the 32 page/16 spread format and staying under the normal limits of word count: usually 500 to max 1000. - Middle Grade & YA:

– Main character should be 2-3 years older than the intended audience.

– Language should be age appropriate (in complexity and content).

– Ending should be hopeful and usually have clear closure, but also hint at future growth.

– Themes should be geared towards the intended audience (being true to oneself, doing what’s right, etc.).

Constructive comments:

- “You have identified this submission as for [whatever age range], but because of [the character’s age/theme/language], this piece feels more like [whatever age range].”

- Consider the voice of your character, and if it matches the audience’s age / the age of the character you are writing for: “The voice is very strong in [refer to certain parts]” “The voice feels realistic for the age range…”

- “Your world is really interesting, and there are some logistical problems that may strain your reader’s suspension of disbelief/I enjoyed the world that you have built, and I have some logistical questions about this.”

Tips for grading Creative Non-Fiction

Common issues:

- Understanding of sub-genres of creative non-fiction. For example, what differentiates a personal essay from an essay or from memoir?

2. Use of past tenses, e.g., transitioning from past tense to past perfect for flashback in a memoir piece narrated in past tense.

3. Including too much about the process of arranging to meet (or the beginning moments of meeting with) interview subjects in the final piece of writing.

4. The narrator does not establish a strong enough emotional connection to the reader.

5. The narrator summarizes events instead of showing us “close-ups” of meaningful moments and conversations.

6. The piece has a bit of a forced, summative conclusion (the “tied up with a bow” ending). Look out for any conclusions that read more like the conclusion to an academic essay. Remind students that it’s okay to leave some ambiguity, or even to have a “non-ending.”

7. Memoir/essay with a more scattered theme.

8. Too much of scene or summary.

9. More contextualizing information is needed to help unfamiliar readers understand/follow the section/piece/theme/subject.

Encouragement:

- “Thank you so much for sharing this with me.”

- “It was very brave to tackle such serious subject matter.”

- “Thank you for your candid and insightful connection.”

Constructive comments:

- “In memoir and personal essay, you are our main character, and I would like to know more about you as a character and narrator.”

- “Maybe you can consider going deeper here emotionally. Readers would really appreciate emotional honesty and vulnerability.”

- “I enjoy the story that you’re building here and I wonder about the theme of this narrative. [Consider referring to a specific part of the story.] How does it work as part of the larger narrative you are building?”

- “I’d love to see this in scene, instead of summarized./Which moments in this sequence are most important to present to the audience? Consider focusing more on that key moment and cutting other material to strengthen your piece.”

- “What unusual details can you include that will distinguish your story from others? Consider including ‘golden details.'”

- “I would love to see more context or information on this issue.” [Identify the place.]

- “While in academic writing, summarizing your thoughts is very normal, in creative nonfiction, you have more freedom to have an open or ambiguous ending.”

Feedback tips for Poetry

Try to avoid being too prescriptive with feedback for poetry.

Common issues with poetry assignments:

- Need to consider ways that the formal elements of the poem (rhyme, rhythm, enjambment, stanza breaks, etc.) fit with the intention and themes of the poems.

- Need to consider ways to experiment with sound and slant-rhyme rather than being constrained by rhyme.

- Need for specific concrete sensory details and fewer abstractions.

Constructive comments:

1. Language, Details, Metaphor: - “I like your use of language/the phrase [identify specifics]. Consider your diction here: does it match with the feeling, time and place that you are trying to create inside your poem?”

- “More concrete details would help a reader to feel more involved in the poetic experience. Watch how many abstractions you are using, as they can be distancing/hard to hold on to.”

- “You details here are very specific and could be more sensory. Try to use words and descriptions that your readers can smell/taste/touch/see or hear.”

- “Your metaphor here is very creative! However, I’m not sure it works on [this level]. What other metaphor could you use here to get across exactly what you want to say?”

2. Syntax, rhyme, etc.: - “I’m noticing there is some rhyming in this poem, but it is not consistently present. I’m wondering if you are trying to create a pattern or not, and would recommend either enhancing or removing this element, as it may distract readers from the meaning of your poem.”

- “Sometimes your lines felt like they were being written in service of the end-rhyme; don’t let one sonic element dominate your poem too much, as it can get in the way of other aspects of writing good poetry (meaning, flow, diction choices).”

- “Check out Rhymezone (https://www.rhymezone.com/), if you feel like you’re struggling with finding good rhymes (but look up the word before you use it to make sure you’re saying what you want to say!)”

- “I am not sure that your line breaks are serving you [sonically/in terms of communicating your meaning]. Have you considered using [longer lines/enjambment/something else]?”

3. Clarity: “I had trouble following [this section]. Consider ways that you could improve clarity here.”

Feedback tips for Graphic Forms

Constructive Criticism:

1. Be careful with letting the words do most of the work. Try and find space for the images to breathe and also contribute to the overall sense of the panel.

2. Remember that your reader will be reading from left to right, top to bottom, so you have to honour that instinct for the sake of comprehension.

3. Try and think of ways that the images can not only work as themselves, but also as metaphors. For example, if your comic is exploring friendship, there could be two trees in the distance topping a lone hill. That’s basic, but hopefully you understand the point.

4. Leave more space for the “gutters” between panels. If there are too many panels bunching up against each other it becomes harder to read.

5. Choose a consistent font. Changes in font size can make it harder for the reader to follow along.

6. Always seek to achieve a balance in each panel, with the right amount of space given to words and the right amount of space given to pictures. This is always changing, but usually because of context. A big, open panel with few to no words will give a sense of pause and contemplation, causing the reader to linger (usually for a reason), just as small, quick panels featuring a lot of dialogue and only talking heads will hurry a conversation along.

7. Images (particularly characters) with a sense of movement are always more fun to look at than static panels/characters. They also allow the eye to flow through the panel easily, and will make for better reading all around!

8. Avoid any redundancies! If the caption says “He is sad” and the image is just of a guy crying and saying “I am sad” there will be a huge disconnect between the work and the reader.

Praise:

1. Great use of space and balance. Allowing the images to work alongside the pictures gives your comic a real sense of togetherness and completeness. Well done.

2. Great use of panels, for the purposes of pacing and for deliberately manipulating the reader’s eye. There were some great moments when the eye could just linger for a while and soak in the panel, and other moments when there was barely a pause for breathe. Wonderful pacing all around.

3. I love how you’re allowing for some images to become metaphorical, and you’re avoiding redundancies. Each element is working separately and achieving a cohesive whole, and that’s wonderful. Some images are transcendent and powerful.

4. Excellent way of avoiding redundancies. The images and words are working together, but separately.

Feedback tips for Screen

1. Formatting is much more important in screenwriting than arguably any other genre. Thus, assignments are almost always partially graded on correct formatting. The problem is that screenwriting formatting can be flexible at times, and not at others. An example: every time a script has a new scene, it gets a Scene Heading/Slugline (example: INT. CLASSROOM – DAY). A slugline can be in caps, it can be in caps and bold, and it can be in caps, bold, and underlined. But it has to be consistent throughout. There are numerous other grey areas like this. The important thing is to make sure you or your instructor communicates to the students what is accepted beforehand.

2. While part of marking screenplays can be black and white like formatting, it can often be more difficult to grade a story (like most any other genre). One way to assess student scripts is based on the simple screenwriting principles that are taught in almost every undergrad screenwriting class. Things like CHARACTER and MOTIVATION (who’s the main character, what is their goal, what are the obstacles in the way of that goal), etc., and DIALOGUE (do characters sound different, is it intriguing or overly expositional, is there too much or too little dialogue). While it can be tough to grade creative work, going back to the basics often helps for screen.

3. It’s important to make sure you’re on the same page as the other TAs when it comes to technical stuff like format marking. If you’re deducting points for each italicized slugline, but the other TAs aren’t, this can come back to bite you if a student figures this out. So get together and have a chat about how the assignments will be marked beforehand. (OR grade a handful of assignments together as a group before setting off on your own!)

Feedback tips for Stage

Common challenges for students who are new to Playwriting:

1. Specificity of voice and characterization: Encourage students to read the work aloud with a friend after a first draft – do the characters all speak the same? Do they always understand what one another are saying?

2. Storytelling through dialogue: Encourage students to think about how story and character are revealed through what people say, how they say it, and what they don’t say.

3. Ask students to consider whether there is conflict. Do the characters have clear objectives? Are there things/people getting in the way of their objectives? Do they achieve their objectives?

Sample Comments:

1. Think about which stage directions are important. Consider editing them down for more clarity and simplicity. What does the audience see?

2. The characters have opposing objectives which brings great stakes.

3. The elements of your play are working well together, including setting, character and time. Staging has been carefully considered.

If you have any further questions, feel free to talk to the course instructor, a TA mentor, a more senior TA on your team, or the TA coordinator.

If you have any tips or examples that you’d like to submit, please leave a comment or send them to crwr.taadmin@ubc.ca.

Thank you!