Can you read this and tell me what you think?

A question you’ve been asked many times over, either in the mad flurry at the end of class, during office hours, over email, sometimes even on your way to get lunch between workshops. What the aspiring writer wants from you is varied: validation, encouragement, acknowledgement, individual attention, line edits, or, quite simply, to be told what to do. An authentic, meaningful response is impossible under these conditions. And yet, here you are.

Here’s a process-oriented response to this question, borrowed from arts-based pedagogy, that aims to situate the work within a larger network of the writer’s questions, curiosities, influences, and resources.

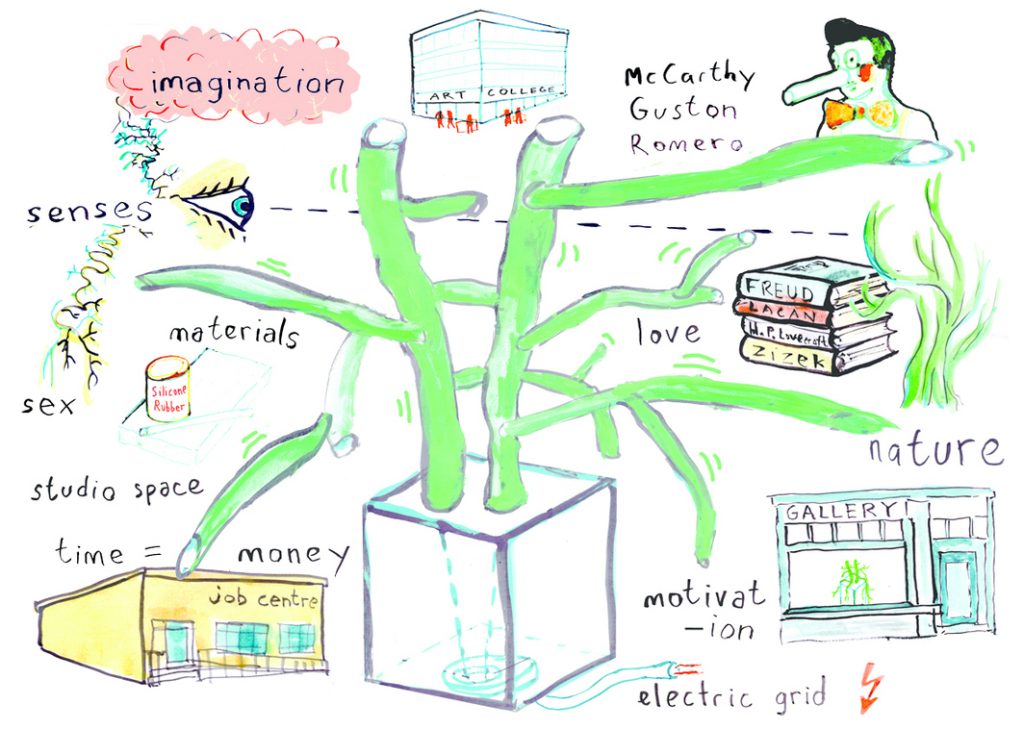

Social Body Mind Map in Visual Arts

From Dean Kenning:

-

- Social Body Mind Mapping is a diagrammatic tool to enable critical reflection on one’s (previous, current or future) artwork with respect to unconscious process and social forces.”

- Through this creative thinking tool, art manifests a capacity to open up different ways in which we, as desiring individuals, connect to, and are caught up in, intricate social networks of influence and possibility.

- Key to this capacity is a necessary shift away from the idea of a ‘self’ as a pre-established identity from where artworks spring (whether from a brain, innate talent, personality, cultural background, etc.)

Adapting for a Creative Writing Context

This approach works well with individuals as well as small groups. For this example, let’s imagine a small group of keen students during office hour.

Begin by inviting students to brainstorm:

Where does a piece of writing come from?

What makes it possible?

Together, generate lists under the following headings. You can offer a couple of examples from each category to get them started:

At this point, you can move to the mapping process.

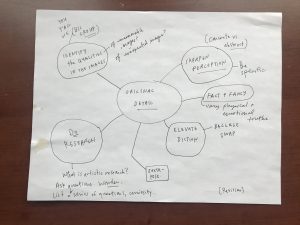

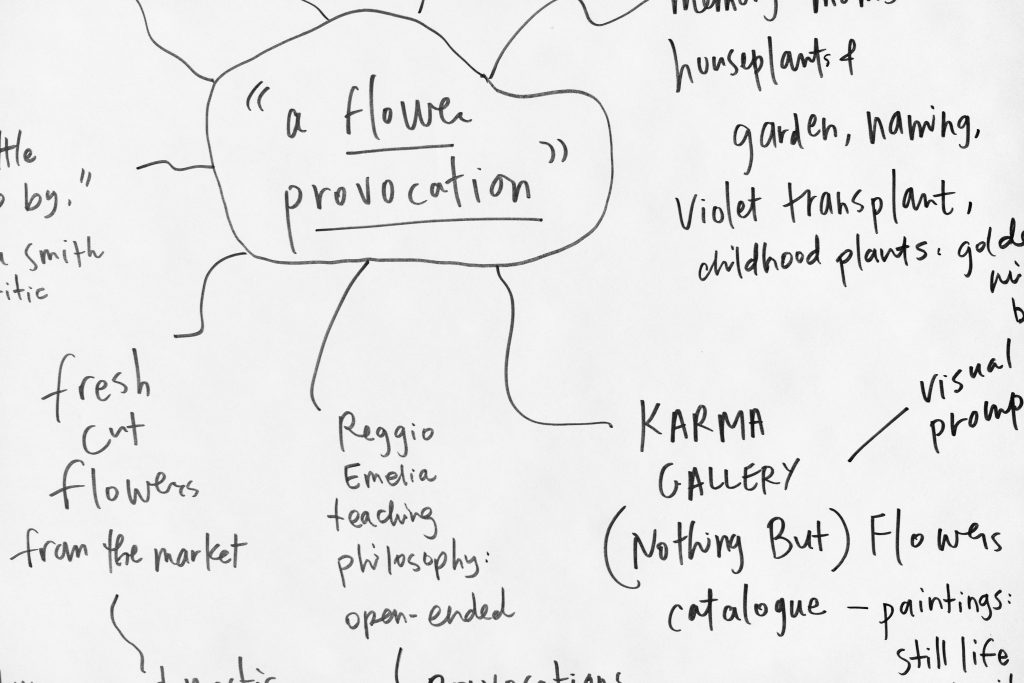

Ask students to draw a circle at the centre of a large piece of paper, and place the title of the piece of writing (or, if they’re inclined to draw or doodle, an image from the work). From the title, they begin to map the capacities, motivations, and influences that facilitated the work. Here’s an example from a map I made of a future poem:

Now I can see the connections between different elements / images I’ve been thinking about: memories of my mom’s garden, the catalogue of flower paintings from a show during the pandemic, the fresh flowers I buy at the market each week, quotes from other writers about flowers, and some formal considerations (off map).

What is illuminating is seeing everything all at once, and knowing now what influences I need to return to in order to make specific observations, perform more research, and otherwise attend more closely. Someone reading my map may be able to illuminate a connection I’m not seeing, or offer suggestions for further resources, such as paintings I might look at, or a pop culture reference I may not be aware of, in order to broaden the work.

REFLECTION

With the student’s map in front of you, you have access to context around the work, which allows you to make relevant observations, ask productive questions, and suggest informed craft moves. What will become immediately apparent, for example, is a total lack of capacity or motivation, other than “it’s an assignment for class,” so questions about what they would rather be writing, given the chance, may prove fruitful.

Working together with the map, what’s possible within the work will become apparent, as well as what parts of the process of making the writer might need to attend to, return to, engage with, or enhance. You can also ask students to share maps, so that they may respond to what they’re seeing and make suggestions to one another.

OBJECT LESSON

At its heart, this process-oriented approach invites students to see creativity as an integral and essential part of who they are and how they live in the world, and to view their work as part of a much broader ecosystem of creative forces.

In order to truly understand the potential impact of this mapping approach, I invite you to try it out for yourself, beginning with a past, present, or future piece of writing and seeing where the process of mapping takes you.

Sometimes the map becomes the art object…

Have fun!

Resources:

Learning to Teach Art and Design in the Secondary School, ed. Nicholas Addison and Lesley Burgess

Dean Kenning’s work: https://www.mattsgallery.org/artists/kenning/exhibition-1.php