In the fall of 2019, the instructor for the course I was TAing asked me whether I’d like to present a small lecture to the class. Although at that point the extent of my personal experience with lecturing was instructing a dozen middle schoolers at a summer camp, I knew this would be a valuable opportunity to develop as a teacher. I agreed, and began charting out my first lecture.

I doubt it will come as much of a surprise that writing that first lecture with no prior experience was, in fact, pretty difficult. But the process taught me much about how to present a lecture in a university classroom setting. If you’re a new TA faced with the prospect of preparing your first lecture, I hope these notes will be of some use.

Topic

It’s hard to start writing a lecture if you don’t know what you’re lecturing on. Your instructor might have already selected your topic in advance, but I’ve also worked with instructors who let TAs select their own topics.

The topic of the lecture I gave was assigned to me based on my current line of work—indie video game writing—which filled a niche that had been vacant in the course. But if I had been able to choose a topic, I would have made the same choice. In my view, lecturing on a subject within my experience offered two major benefits—first, it let me speak on a subject I was already very familiar with, which is great for mustering confidence when you’ve got a bad case of stage fright; and second, it meant that the students would (hopefully) be getting a more useful lecture, one grounded in practical experience.

As the instructor told me while I was outlining, the students are there because they want to get something for themselves out of the lecture. If you can offer something unique, like your personal perspective and expertise, then everyone benefits.

Visual Aids

Regardless of what you end up presenting on, I think visual aids are invaluable. Almost every classroom at UBC has a projector on hand, so slideshows, like a Powerpoint or Prezi, tend to be the most common form of visual component.

The best advice I’ve heard is to avoid letting your slideshow make your voice redundant. If the slides contain everything you say aloud, the audience will simply read the information off the slides and stop paying attention by the time you get around to saying it. It’s more useful if the slides focus on the key concepts that the audience will want to take away; if you were taking notes as you listened to the lecture, what would you write down?

Aesthetically, there are two main schools of thought on how to design a slideshow: stylized, with a touch of decoration to keep it visually engaging; or minimalist, with no decoration, in order to focus on clear presentation of the information. I’ve seen both looks executed well, and I don’t think either is better than the other. That said, I did go with plain white text on a black background for my presentation, with the hope of making the slideshow easy to both produce and read.

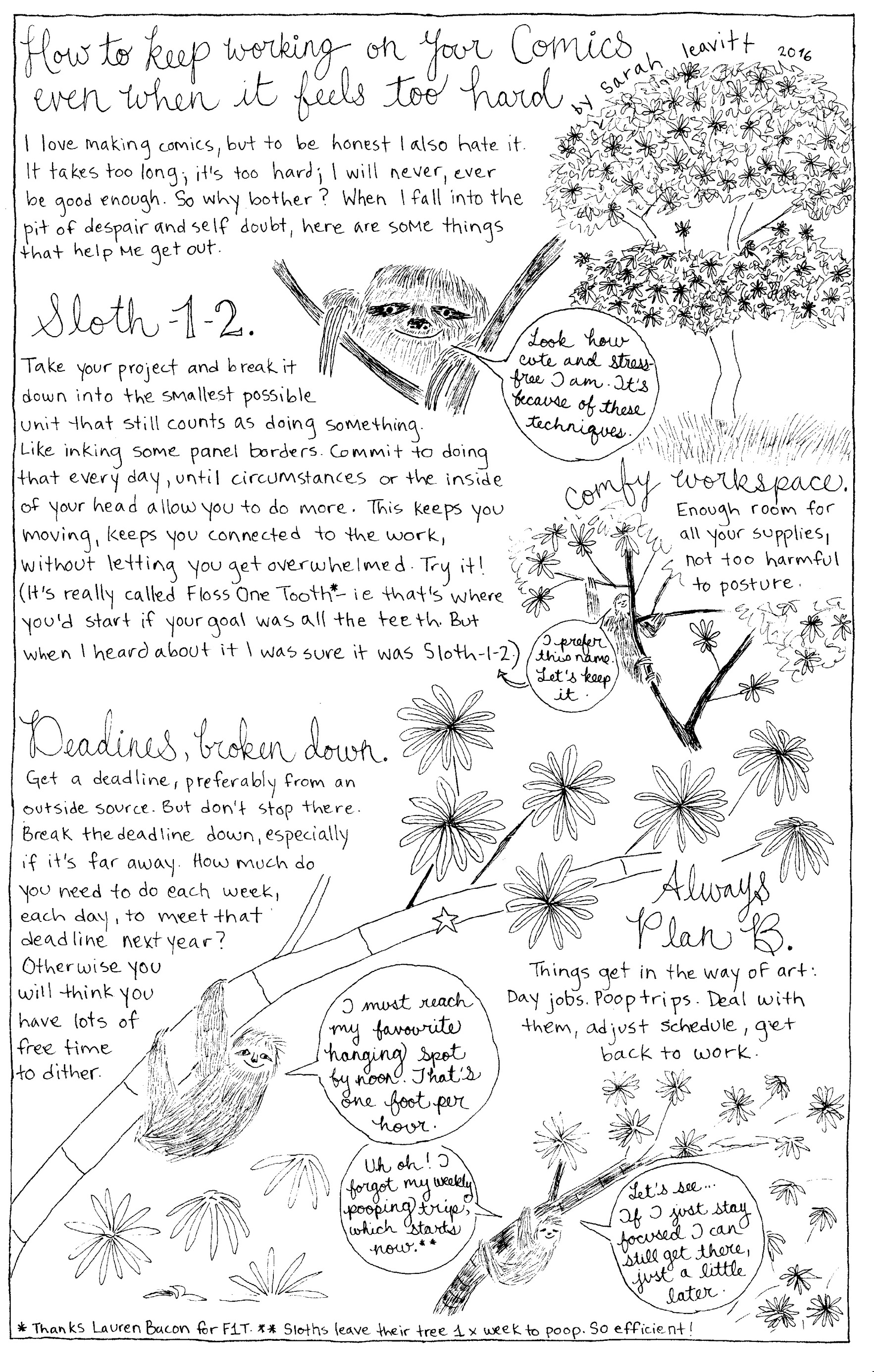

Script and notes

During my first TA orientation, one of the instructors remarked that he usually had his TAs throw out their notecards before presenting—a fact that drew a nervous laugh from the new TAs in the room, myself included.

For this lecture, my initial plan was to write a very polished script, commit it to memory as well as I could through rehearsals, and recapitulate it in class roughly as written with the aid of notecards. While I didn’t want to come across like I was reading from a teleprompter, the prospect of potentially needing to improvise in front of a crowd terrified me. I was confident that a thorough script would help me avoid this problem, and this confidence lasted right up until the moment when I stood at the podium, glanced down at my notes, and realized I actually wasn’t going to have any time to reference them.

But, as it turned out, knowing what to say without a script was really a non-issue. Although I couldn’t reference the words I’d originally written for my script, the process of outlining my ideas and drafting the slideshow meant that I’d already given a lot of thought to every slide and to the sequence of concepts, and the rehearsals I’d done prior to giving the lecture helped it stick in my memory. When I had to talk about a slide, I didn’t need to consult the notecards to know what my thoughts were on the subject or what to say. Although I’m not sure I’d recommend abandoning your notecards entirely, I don’t feel that they’re necessary for delivering a lecture successfully. Developing a clear vision for what needs to be said and then rehearsing it can serve just as well.

Conclusion

Despite my initial concerns, I feel my first lecture ended up going fairly well—and certainly better than I had thought it would when I was going into it. Preparation was the key to success, more so than comfort with public speaking or prior experience as an instructor. This term, I plan to give a revised version of the lecture to the class, hopefully with fewer nerves and no notecards.

Daunting as it was, presenting that first lecture was a fantastic opportunity and a lot of fun as well. If you have the chance to prepare a lecture of your own, I hope you’ll consider it!