Below is Team Coyote’s annotated bibliography, organized by team member.

Guindon, François. “Technology, Material Culture And The Well-Being Of Aboriginal Peoples Of Canada.” Journal Of Material Culture 20.1 (2015): 77-97. Business Source Complete. Web. 6 Aug. 2016.

François Guindon addresses the needs for cultural well-being through a discussion of the transformation of technology and culture for the Mistissini Cree from the 1940s to 2012 (77). This transformation is applied in a way that challenges the colonial forces (ex. missionaries, traders, government etc.) that reinforce misconceptions of Aboriginal healing practices, psychological, material and physical well-being (77). The process for healing is defined as the self forming a connection with community, land, cultural heritage (81); which were all stripped away in attempts of cultural genocide like the Indian Act and the Indian Residential School system. Guindon argues that technology and material welfare are important characteristics of cultural heritage that are linked to the well-being of the Mistissini Cree people (77).

Furthermore, Guindon argues that healing/well-being for Indigenous people are linked to Aboriginal technologies through analyzing how recent theories have overlooked the role of the physical world (92). The study of the Mistissini has challenged misconceptions regarding the relationship between mind, body and material in regards to Indigenous well-being (92). This article relates to our topic because Guindon aims to highlight the restorative psychological/physical well-being methods through studying the Mistissini population. This challenges the misconceptions caused by colonial theories that over look the importance of healing through understanding the Mistissini perspective of forming a connection with land, heritage and members of the community.

Stewart, Suzanne. “Family Counseling As Decolonization: Exploring An Indigenous Social-Constructivist Approach In Clinical Practice.” First Peoples Child & Family Review 4.2 (2009): 62-70. Bibliography of Native North Americans. Web. 6 Aug. 2016.

Suzanne Stewart is an assistant professor at the University of Toronto who specializes in Aboriginal healing in the field of counselling psychology. In her article, Stewart’s main point of emphasis is analyzing the Indigenous people’s relationship with their families through the ‘Indigenous way of knowing’ through connecting with the earth and the community (62). Moreover, Stewart focuses on the concept of social constructivism in achieving this Indigenous way of knowing in family counselling because it recognizes culture and human interaction when forming knowledge on the basis of this understanding (62).

Furthermore, family practitioners can form a hybrid method comprised of Western and Indigenous approaches in addressing family counselling practices for Indigenous people. This hybrid approach is a step towards improving communal mental health in recovering from colonialism and cultural genocide, which is a clinical example in relation to our topic in taking steps towards cultural preservation and recovering from colonialism (62).

Works Cited

Vancouver IdleNoMore. 9 Nov. 2013. The Marxist-Leninist Daily, Cpcml.ca, Vancouver. Www.cpcml.ca. 9 Nov. 2013. Web. 11 Aug. 2016.

Noël, Paula. “Colonization and the Recovery of Indigenous Mind.” Community Connexion. Paula Noël, July 1999. Web. 06 Aug. 2016.

Robbins, Julian A., and Jonathan Dewar. “Traditional Indigenous Approaches to Healing and the Modern Welfare of Traditional Knowledge, Spirituality and Lands: A Critical Reflection on Practices and Policies Taken from the Canadian Indigenous Example.” The International Indigenous Policy Journal 2.4 (2011): 1-17. Web. 6 Aug. 2016.

Swallow, Johnny Huskey, and Charlotte Huskey Swallow. “Mistissini.” Creeculture. Cree Cultural Institute, n.d. Web. 06 Aug. 2016.

“Traditional Healing.” Traditional Healing. First Nations Health Authority, 2016. Web. 06 Aug. 2016.

~ Deepak Nijjer

Highway of Tears. Dir. Matthew Smiley. Carly Pope. 2015. Film.

Photo Credit: Wikipedia. Sept 8, 2013. Web. August 9, 2016.

Highway of Tears is a documentary written and directed by Matthew Smiley, a Montreal-born producer and director who has credited making the film with spurring his entry into activism. The long stretch of highway between Prince George and Prince Rupert, along which over half the murders and missing woman have been First Nations, “is the nucleus of a much larger problem,” states that film’s narrator, one of “how the Indigenous population have been treated since colonialism” (Highway of Tears).

The documentary cites systemic racism/indifference and Canada’s colonial past as the root of the tragedies that occur along the Highway of Tears. Unfortunately, many of the proposed solutions (calls to action) by Indigenous communities that have been affected have not been implemented or have been disregarded altogether. Other organizations, though, including the Native Women’s Association of Canada and Human Rights Watch, have taken great issue with the over 600 reported missing/murdered Aboriginal women in Canada.

Smiley’s documentary is a useful resource for researching the effects colonization has had on Indigenous women in many ways: for one, it interviews family members of the victims and allows them to tell their firsthand narrative accounts (without media bias)— whether they talk of their mothers, sisters, or daughters who are missing or were murdered along the highway, each unique perspective is given a platform. The film also discusses ways to “forge a new future with impartial eyes,” explaining that the effects of colonialism on Indigenous women cannot simply be reconciled via one project or one initiative; rather, it suggests to viewers that a changing of mindset and of heart is necessary, and above all, conversation about what has happened (Highway of Tears).

Works Cited

Carrier Sekani Family Services, Carrier Sekani Tribal Council, Lheidli T’enneh First Nation, Prince George Native Friendship Center, Prince George Nechako Aboriginal Employment & Training Association. The Highway of Tears Symposium Recommendations Report. Turtle Island Org. 16 Jun 2016. Web. 9 Aug 2016.

“Fact Sheet: Missing and Murdered Aboriginal Women and Girls in British Columbia.” Native Women’s Association of Canada. 24 Mar 2010. Web. 9 Aug 2016.

“Highway of Tears emails deleted, alleges former B.C minister staffer.” CTV news. Bell Media. http://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/highway-of-tears-emails-deleted-alleges-former-b-c-ministry-staffer-1.2396611. 28 May 2015. Web. 9 Aug 2016.

“Highway of Tears: Watch the Film.” Web. http://highwayoftearsfilm.com/watch. Accessed 9 Aug 2016.

“Media Portrayals of Missing and Murdered Aboriginal Women.” MediaSmarts. Web. 9 Aug 2016.

“Those Who Take Us Away: Abusing Policing and Failures in Protection of Indigenous Women and Girls in Northern British Columbia, Canada.” Humans Rights Watch. Jul 2012. Web. 9 Aug 2016.

~ Victoria Woo, August 9 2016

Feinstein, Pippa, and Megan Pearce. Review of Reports and Recommendations on Violence against Indigenous Women in Canada: Master List of Report Recommendations Organized by Theme. Legal Strategy Coalition on Violence Against Indigenous Women, 2015. Web. 13 Aug 2016.

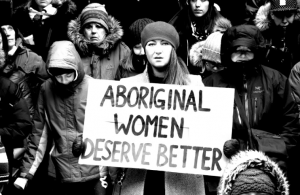

Protesters outside the Toronto Police Headquarters calling on Canada to act.

Protesters outside the Toronto Police Headquarters calling on Canada to act.

Photo Credit: S. Amy Desjarlais, Murkrat Magazine. Feb 26, 2015. Web. Aug 13 2016.

Pippa Feinstein and Megan Pearce, both Toronto-born lawyers with special focuses in social justice and human rights, each co-authored this comprehensive document which reviews all the existing literature (reports and recommendations) concerning violence against Indigenous women in Canada. This document is unique in that it discloses the extent to which these reports and recommendations have actually been implemented (as of the publication date in 2015).

Feinstein and Pearce’s central concern, as outlined in the document, is that there has been an overwhelming lack of recommendations implemented (or even considered at all), particularly at the federal level. Within the sixteen thematic categories, none have fully implemented recommendations made to help prevent and rectify instances of violence against Indigenous women. In many of the categories, such as in “Aboriginal involvement in program development and delivery,” federal and provincial governments have made “attempts” at involving Indigenous women in the development of culturally-sensitive programming, yet countless Indigenous women remain concerned about inadequate consultation processes associated with new government policies which primarily affect Indigenous women (Feinstein and Pearce, 15). Feinstein and Pearce’s comprehensive review is worthy of consideration in three ways: 1) it precisely demonstrates the underlying disconnect between what the Canadian government claims to have done/be doing, and what has actually effectively been done, 2) it inspires important questions and concerns about the role that the Canadian government has, or should have (if at all), in addressing matters as they concern Indigenous women, and 3) it demonstrates the resilience and strength of Indigenous women and their communities, who have fought for and continue to fight for their safety and well-being.

As this document was published while former Prime Minister Stephen Harper led the Conservative party, is it reasonable to assume that changes have occurred since Justin Trudeau was newly elected this year in 2016. While the new Liberal government has touted real change and reformation, Senator Murray Sinclair of Truth and Reconciliation says that change is still elusive, and that he still “cannot say that [he is] satisfied with the way things are going.”

Works Cited

Galloway, Gloria. “Native Leader frustrated by lack of consultation with Ottawa on job program.” The Globe and Mail. 22 Mar 2013. Web. 13 Aug 2016.

Mas, Susana. “Truth and Reconciliation Report: 1 Year After, Change Is Still Elusive, Sinclair Says.” The Huffington Post. 2 Jun 2016. Web. 13 Aug 2016.

~ Victoria Woo, August 13 2016

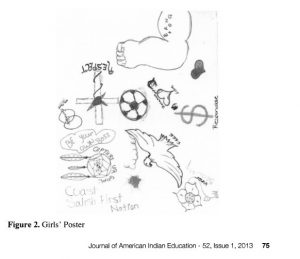

An example of the art created during the 16-week study by a young Indigenous girl. Banister, Elizabeth M. and Deborah L. Begoary. “Reports from the Field: Using Indigenous Research Practices to Transform Indigenous Literacy Education.” Journal of American Indian Education 52:1 (2013): 75. Web. August 12, 2016.

Banister, Elizabeth M. and Deborah L. Begoray. “Reports from the Field: Using Indigenous Research Practices to Transform Indigenous Literacy Education: A Canadian Study.” Journal of American Indian Education 52.1 (2013): 65-80. University of Minnesota Press. Web. August 12, 2016.

In their study Elizabeth Banister and Deborah Begoray aimed to rectify the damages done by Western learning hegemony on Indigenous communities, focusing in particular on literacy rates. First Nation communities in Canada experience only a 50% graduation rate as opposed to the non-Native average, which hedges around 90% (Banister and Begoray, 68) (off-reserve communities often fair better, but the graduation rate is still below average). During a two-year, 16-week at a time interactive program with the Coast Salish First Nation Hul’qumi’num, Banister and Begoray worked with a group of Indigenous girls to facilitate interest in literacy, sexual health, and to improve overall communication between the girls and the teachers, and between the girls themselves.

Banister and Begoary note in their study that Indigenous learning techniques differ from Western in a a few key ways; one, it is more community-led, with Elders passing down stories, two, visual artifacts and stories are more readily used, and three, Indigenous learning practices are less hierarchical. By hierarchical, Banister and Begoray point to the difference between a Western classroom, where the power is concentrated in the teacher, and an Indigenous classroom, where the power is more readily shared, and where Indigenous young adults are expected to “be responsible for their own lives” and to take a degree of agency and self-direction in their learning (Banister and Begoray, 66). The steps they took to incorporate Indigenous learning techniques into the classroom were, to name a few, reiterating the value of Indigenous knowledge (instead of overriding it with Western concepts), including spirituality into teaching methods, and finally, allowing trust back into the classroom. At the end of their study Banister and Begoray believed that the meld of Indigenous and Western learning techniques greatly benefited the girls they studied with and their own teaching methods, while also showing that there is a still a long way to go.

Works Cited

Dehaas, Josh. “First Nations dropout rate falls, but less so on reserves.” Macleans. Rogers Digital Media. May 2, 2014. http://www.macleans.ca/education/high-school/little-progress-in-on-reserve-dropout-rate-report/. August 12, 2016.

Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group.http://www.hulquminum.bc.ca/hulquminum_people. Accessed August 12, 2016.

~~

Cover art for Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood.

Scott, Jamie S. “Religion, Literature, and Canadian Cultural Identities.” Literature and Theology 16.2 (2002): 113-26. Web. Accessed August 13, 2016.

Jamie Scott’s article is in fact an introduction to a special issue of Literature and Theology, an issue which focused on six essays by Canadian writers; the essays themselves focused on Canadian identity. Scott details the efforts made at finding an answer to the identity question — novels from the 1800s, which portrayed Canada as a wild, untamed Eden; Two Solitudes, a 1945 novel which looked at the tension between Protestant English and Roman Catholic French; and contemporary Margaret Atwood, whose use of Native American spirituality allowed her to “explore avenues of self-discovery free from the patriarchal traditions of [her] own culture and society” (121). Scott notes that while in the past the crux of Canadian identity has been largely focused on the struggles between religion, specifically Protestant and Roman Catholic, those struggles have always, even intentionally, left out the violence religion has played on the Native communities (118, 120). Scott notes that Native writers such as Thomas King have taken it upon themselves to reveal the violence which came part and parcel with Canadian missionaries (118); however, Scott stresses that the onus should be on Canadian readers and writers to “de-christianize” Canadian literature, and to introduce Native writers with more force into school curriculum and public debate in order to recognize past wrongs and to change “mainstream culture” into one more introspective, empathizing, and focused on rectifying inequalities (121).

Scott’s introduction does not just illuminate the silencing of Native voices, but also the voices of immigrants who arrived after the passage of the Canadian Multiculturalism Act of 1988. As Scott notes, Canada is not so much multicultural as a “transcultural kaleidoscope of social and cultural identities” (122), and simmering resentment after terror attacks over seas, the “burning of a Hindu temple in Hamilton, Ontario” after 9/11 (123), and prevalent xenophobia are examples of the tensions still within our society despite the open stance taken in 1988.

Works Cited

“Arrests in post 9/11 ‘hate’ attack on Hamilton Hindu temple.” CBC. CBC Radio-Canada. November 27, 2013. Web. Accessed August 13, 2016.

Besner, Neil. “Two Solitudes.” The Canadian Encyclopaedia. N.P. February 6, 2006. Web. Accessed August 13, 2016.

— Mia Calder

This is a sheet of cancelled land scrip certificates, January 20, 1905, RG15, Vol. 1406

In her study of Colonization and Racism, Dr. Emma LaRocque, a Plains-Cree Métis as well as a professor in the Department of Native Studies at the University of Manitoba, addressed the impact that colonization had on the many tribes of Indigenous people in Canada. She provided countless examples of how these people were able to be legally – albeit unfairly – forced out of the land that they had grown up in and called home for as long as they could remember. One such policy that was passed allowing this to happen to was the Scrip program, which was designed to forcefully separate the Métis people from their land. This program appeared to be benevolent at first, offering the Métis “scrips” of land for them to keep. However, it would soon be realised that many of the Métis were offered scrips that were unreasonably far from where they originally lived, forcing many of them to relocate hundreds of miles away from their original communities and extended family.

The application to this program was also unreasonably complex – designed, in fact, to intentionally confuse the applicants and obscure the legal implications of what they were giving up when they agreed to scrip. As a result of this, the Métis Nation peoples lost around 83% of their Red River lots as part of the program. Programs such as these played their part in allowing the Europeans to, in a sense, “take over” the land that initially belonged to the Indigenous people, by offering to them programs that, at first glance, seemed beneficial and fair to them – but would ultimately be detrimental to their ability to retain their rights to the land that they called home.

Learning about programs such as the Scrip Program will ultimately allow us to better understand what Indigenous people went through in the past, and from there provide a better foundation from which we can build up solutions that we may find in terms of helping others to reconcile with the past.

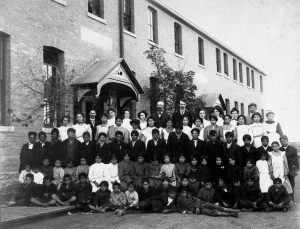

Residential school group photograph, Regina, Saskatchewan 1908

Another method that colonizers used in order to rationalize their unfair oppression of the Indigenous people was through racism. As LaRocque emphasizes, racism against Indigenous people can be traced in history within Canadian institutions. Some of these include “the British North America Act, the courts, the police, churches, banks, employers, social services, the medical system and education.” As a part of the colonial project, Europeans could be found categorizing themselves as “civilized,” while categorizing the Indigenous people as “savages.” LaRocque notes especially that in the Western interpretation of history, an extremely biased interpretation of history has been passed down for generations through the “uncritical use of archival and historical records and textbooks.”

As a result of the biased interpretation of history that was taught in schools, the concept of racism has been deeply institutionalized to the point that it has many in White North American society inherently do not even realize that their thoughts are racist or damaging to another group of people. In addition to these, residential schools were, in the past, enacted with the sole purpose of eradicating the “Indian” in the children of the Indigenous people. It is because of these reasons that it is of utmost importance that we continue to provide courses that will shed light on history that is told by the voices of those other than of one perspective – especially those belonging to the Indigenous people. In fairness, Canada has taken many positive steps in the direction of recognizing and eradicating racism, with Acts such as the Employment Equity Act of 1986, and the Canadian Multiculturalism Act of 1988 In shedding some light on how colonization and racism has impacted the Native people, we can then better understand how to find ways in which we can help to reconcile with the past.

Works Cited

Hutchings, Claire. “Canada’s First Nations: The Legacy of Institutional Racism.” Canada’s First Nations: The Legacy of Institutional Racism. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Aug. 2016.

James, Lou. “Aboriginal Racism.” Aboriginal Racism. Huffington Post, n.d. Web. 13 Aug. 2016.

Joseph, Bob. “The Scrip – What Is This and How Did It Affect Métis History?” The Scrip – What Is This and How Did It Affect Métis History? Indigenous Corporate Training Inc., n.d. Web. 13 Aug. 2016.

Kirkup, Kristy. “Canadians Not Racist but Aboriginal Issue ‘invisible’ to Many, Says Paul Martin.” CBCnews. CBC/Radio Canada, 13 May 2016. Web. 13 Aug. 2016.

LaRocque, Emma. “Colonization and Racism.” Aboriginal Perspectives. National Film Board of Canada, n.d. Web. 12 Aug. 2016.

– Amelia Yap