FINAL PROJECT: GEOB270

Over the last few weeks, my team and I have poured dozens of hours of work into our final project for the course. We came up with the idea of identifying gentrifying areas in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside and examining the interaction between these spaces, and various elements of resistance and factors contributing to the gentrification of the area. Our goal was to display three overarching themes of discussion:

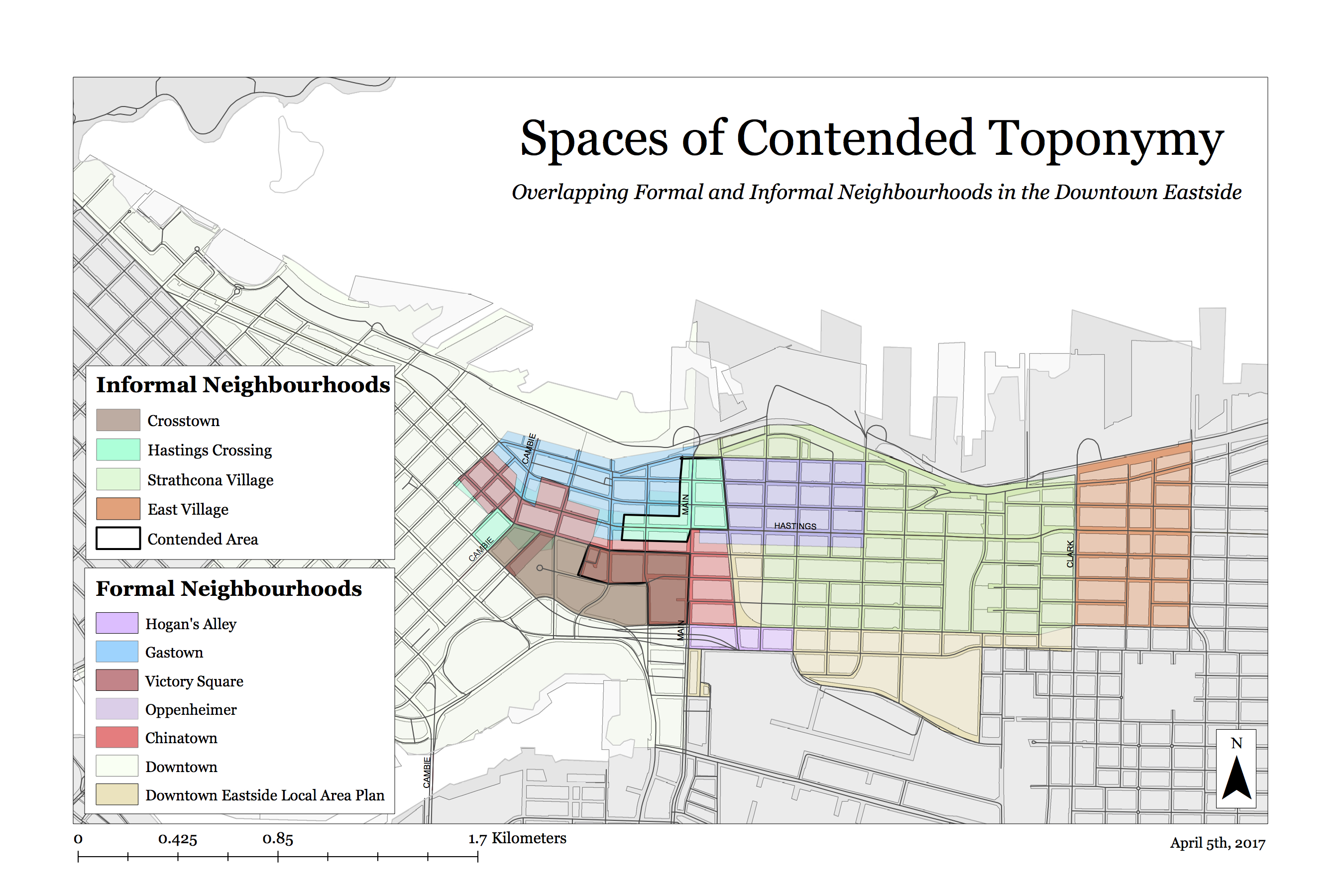

- There are conflicts of naming within the Downtown Eastside, between existing areas (ie. Chinatown) and names proposed by new developments (ie. Crosstown). These new names contribute to an erasure of the history of the area, and a transition to a newer, more expensive neighbourhood. This transition excludes members of the community who resided there in the past, and are unable to afford the increased price of local services and steep hike in property values.

- We believe there are areas of resistance to the gentrification happening on the Downtown Eastside. Homeless shelters and areas of non-market housing may contribute to the preservation of these areas – we wanted to create a map to display the strength of these factors in the proposed redevelopment areas.

- There have been exorbitant increases in Vancouver’s property values over the last few years, and even within the last year. Many of these increases happen within the boundary of the Downtown Eastside and are evidence for gentrification.

We created maps based on each of these points.

Project Management

Each team member contributed to the visualization of the maps and participated in their creation, using ArcGIS software. We worked together, and were able to troubleshoot many of the questions we had in using ArcGIS functions, as relatively new users of the software.

Learning

- We learned about the reality of gentrification in Vancouver, and how rapidly this is occurring. For years, the Downtown Eastside has been an area of concentration for services that many lower-income or homeless residents rely upon. It is possible, through a complete gentrification of the area, that these services may disappear and residents will be forced to relocate elsewhere – but there is a lack of comparable spaces in the entirety of Metro Vancouver.

- We used a new GIS function: the point density tool. This enabled us to create a heat map of the region using the variables of homeless shelters and non-market housing. It was a really effective way to visualize the data.

- It is difficult to coordinate an entire team’s presence during a project – unless the course is their only full-time commitment. However, each of our team members was juggling other responsibilities: paid work, extracurricular community work, other coursework, and exams and final assignments. The dynamic was strongly impacted whenever one of the group members was unable to work – individual work did not progress as quickly or as effectively as work that was completed with at least one other member.

- We relied upon using the computer lab login information of one team member to organize our data in once central H:DRIVE. However, this was sometimes a barrier for simultaneous work as we didn’t think to use USB sticks until later.

This project was a transformation experience in using GIS software, and was a powerful complement to our research topic. Please find the full report below!

Abstract

Our purpose is to address and identify parts of the Downtown Eastside (DTES) of Vancouver that are especially vulnerable to cultural identity loss and displacement. We do so by displaying local geospatial data to create a trio of maps, two displaying modes of spatial oppression, one displaying spatial resistance. The first map displays toponymy (place naming) as a form of political oppression rooted in processes of urban renewal. The second map uses spatial data for key housing services to identify spaces of resistance within those spaces of toponymic oppression, and the third map uses property value assessment increases to display emerging areas of economic exclusion in Greater Vancouver. By displaying the overlap of informally and formally named neighbourhoods in the DTES, the clustered distribution of non-market housing and homeless shelters in spaces of oppression and cultural identity loss, and the increase property value in these same spaces, we hope to generate a comprehensive representation of the current gentrification and urban renewal happening in this area through a unique lens. Our objective is to bridge the gap between theoretical toponymy imposition, and its concrete effects on the livelihoods of the people and neighbourhoods of the DTES.

Description of Project, Study Area, and Data

Definition of key terms:

- Gentrification: the phenomenon of the imposition of “the gentry”, or middle-class people on areas that were originally designated as spaces for racialized or people of a lower socio-economic class. Gentrification may have the result of making spaces unaffordable, unsafe, or unwelcoming for marginalized people, and may result in their displacement.

- Urban renewal: the redevelopment of an area to higher density in buildings, often displacing businesses and people who lived in these areas previously

- Development: a proposal or act of the construction of a new building, can also refer to an existing building

- Spaces of resistance: spaces that are actively serving as a resistance to processes of gentrification and urban renewal

- Toponymy: the act of naming places

- Economic exclusion: exclusion of people by factor of monetary wealth or economic capital. For example, West Point Grey is an economically exclusive neighbourhood because of high costs of property, housing, and lifestyle.

- Erasure: the erasing of people’s histories of struggle and oppression

The Downtown Eastside is a culturally rich and diverse area of Vancouver, and its “residents value its rich cultural community heritage, strong social networks, green spaces, acceptance of diversity and strong sense of community” (City of Vancouver, 2012, p. 34). This area has also been subject to significant cultural shifts and displacement, urging the City of Vancouver to create a Downtown Eastside (DTES) Local Area Plan to address this issue (City of Vancouver, 2015). This change is incumbent of having spaces vulnerable to growing gentrification, like the emergence of newly named neighbourhoods and developments. One current controversial development that has found itself at odds with the local community that exists in this part of Vancouver is 105 Keefer Street. As a mostly residential development that is well beyond the economic reach of most local residents, it not only imposes itself as an exclusionary space in the urban territory of the local community, but also appears to invite further gentrification in the cultural heart of Chinatown (St. Denis 2017; Mackie 2016).

Our project seeks to spatially identify the most vulnerable zones in the Downtown Eastside to gentrification in three ways. The first is in spatially identifying zones of contended toponymy. Toponymy, or place-naming, is a practice “imbued with meaning,” often used as “discursive agents of power and resistance that perform active roles in the ongoing production of place” (Wideman, 2015, p. ii). It is a process that, through the delineation of new “destinations” and the commodification of space, is political and potentially oppressive in nature (Rose-Redwood 2011b; Rose-Redwood 2011a). Place-naming and the contention of naming a space is a strong dynamic in the Downtown Eastside that we seek to explore through our project. One example of toponymy is found in the map that was posted on the promotional website for Strathcona Village, a major mixed-use development under construction at 900 East Hastings Street. The map on this website imposes unofficial names on areas surrounding the development (“Our Neighbourhood”, n.d.). The emerging name “Crosstown,” is used to identify a portion of what is officially within the local planning area of Chinatown, and is an example of a name that has been used by businesses – and even a new elementary school – in an imposing way (“Crosstown Elementary,” n.d.). Jay McInnes, a real estate agent, provides one definition of what the boundaries of this area are, not mentioning that it is an imposition on an already existing Chinatown (McInnes, 9 October 2009).

The second method spatially illustrates zones of non-market housing and homeless shelters, as indications of resistance against processes like gentrification and urban renewal. These areas also act as representations of spaces that are held for marginalized communities, where they are much needed for residents of these communities.

Our third method of mapping vulnerable spaces is to display increasing property values as a way of indicating zones that may be prone to generating exclusion through increases of rent, eviction, etc. Exploratory research in the field of urban geography by Caitlin Cahill explores not only how those affected by gentrification experience the degrading process of being spatially excluded through increases in rent, but also how these same people observe that this is happening precisely because of the “allure of cultural richness” of these previously low-income areas that exacerbates gentrification (Cahill 2006).

For our analysis, we relied primarily on data from the city of Vancouver’s open data catalogue for shapefiles of official neighbourhoods, property parcels, non-market housing, and others that are created by the municipal government. Tabular data on tax assessments was on the open data catalogue, and was created by the BC Assessment. For place names and important project sites like Strathcona Village and 105 Keefer Street, we created new feature classes based on maps and addresses that were not in shapefile form and had to be replicated. We researched the descriptions of the boundaries of unofficial neighbourhoods – such as Crosstown – and drew each neighbourhood on our ArcGIS map.

Methodology of Analysis

The first layer in each map was the Vancouver mask layer. Relevant layers were subsequently added to each map. The neighbourhood boundaries, including formal and informal neighbourhoods, and the Downtown Eastside (DTES) Local Area Plan were drawn, and were not downloaded shapefiles that were available online.

Map 1 – Spaces of Contended Toponymy

This map shows the overlapping of formal (drawn by the City of Vancouver) and informal (designated by developers or businesses) neighbourhoods, with specific reference to the overtaking of informal neighbourhoods as an act of exclusion, and displacement against already marginalized people. To devise the formal neighbourhoods, we selected by attribute for the Downtown layer, and created a layer out of the selected features. To create the DTES Local Area Plan neighbourhoods, we used street label references to copy the City of Vancouver’s document. To devise informal neighbourhoods, we used maps made by the developers and maps found on association websites of these informal neighbourhoods. To show areas of specific contention between formal and informal neighbourhoods, we made new feature classes and created polygon features, outlining the overlapping areas.

Map 2 – Spaces of Resistance

This map was created to visually represent spaces of resistance within our project boundary. Non-market housing and homeless shelters were used as active examples of resistance to gentrification and urban renewal. We merged the non-market housing points and the homeless shelter points to create a conglomeration of spaces of resistance, and then made a heat map of this layer with low, medium, and high concentrations of points of resistance.

Map 3 – Spaces of Exclusivity

The goal of the third map was to display proportional property value increases for 2016-2017 in our project area, in order to identify areas of property value increase. These property value increases may partially derive from gentrification practices (like place-naming) and new, expensive developments.

For our analysis, we used a modified table derived from the property tax information .xls file from the city of Vancouver catalogue, provided by BC assessments (BCA). This modified table had to be joined to a property parcel layer, and then clipped to our project boundary. In exploring the attribute table of the property parcel polygons layer, and the .xls file for property tax assessment, we found that each property has an 8-digit identifier. In the BCA data, this was labelled “TAX_COORDINATE,” whereas in the attribute table of the property parcel polygons layer this was labelled “LAND_COORDINATE.” When we discovered this, we verified with “select by attribute” for several identifiers to confirm that both labels (“TAX_COORDINATE” and “LAND_COORDINATE”) referred to the same address (both tables contained street and civic number information to confirm this). This allowed us to use this as a join field later on.

First, it was necessary to simplify the original excel spreadsheet into one sheet (the previous spreadsheet contained four full sheets, each with 65 000 rows), so that it could be imported into the geodatabase and joined to the new layer. This simplification was done by generating a list of all the land coordinates for the parcels within the project area, and using this list to filter the rows of BCA data by tax coordinate. The filtered rows were moved into a final sheet of data, where we removed all columns except for tax coordinate, current assessed property value, and last year’s assessed property value. We created a new row with a simple excel formula [((2017 property value – 2016 property value)/2016 property value)*100] to create a field expressing property value increase in the past year. This final excel spreadsheet was imported into the geodatabase and subsequently merged to our layer, permitting the visual analysis of property value increase data across the Downtown Eastside.

Discussion and Results

Map 1 – Spaces of Contended Toponymy

In this map, we show the contended overlap of informal and formal toponymy, and argue that the overtaking of spaces of informal place names is an act of oppression and an imposition of power rooted in urban renewal. (maybe this can be a citation/quote)

In the instance of neighbourhoods like the Downtown Eastside, the imposition of names like ‘Crosstown’ are a form of erasure in the historical context of these spaces. In Chinatown, more than half of its land base designated by the City of Vancouver’s DTES Local Area Plan is overtaken by the newly proposed ‘Crosstown’. This serves as an example of erasure in the historical weight of Chinatown as a place-name; a place where Chinese, Japanese, Black, and Italian ancestors of current residents of Vancouver, came to Chinatown and surrounding areas to build the Canadian Pacific Railway.

In one informal Strathcona Village neighbourhood map we found online, there was no display of Downtown Eastside. The previous name of this area disappeared, and the area was renamed Strathcona. This toponymic exclusion is indicative of erasure and the conglomeration of areas imposed under one name.

The downtown neighbourhood, as defined by the City of Vancouver’s neighbourhood designations, includes much of the Downtown Eastside. The all-encompassing “Downtown” name includes the notes of Coal Harbour, Downtown Core, Gastown, Yaletown, and the Downtown Eastside, which face incredibly different problems and circumstances. The inclusion of the Downtown Eastside in the title of Downtown is an act of erasure that delegitimizes the unique struggles that residents in the Downtown Eastside face. For example, while Coal Harbour improvement associations may worry about having more greenery on the sidewalks where pedestrians are tending to use more to beautify the area, the Downtown Eastside improvement associations may worry about having adequate beds for people to sleep in at night during cold weeks in the region, or they may worry about having enough naxolone kits to help manage the current fentanyl crisis. These areas face very different problems, and the inclusion of the Downtown Eastside especially is an act of erasure of those struggles. When it is included, the entirety of the Downtown neighbourhood barrier is seen as an equivalent area, with the same problems.

Map 2 – Spaces of Resistance

In showing the areas in the Downtown Eastside that are acting as resistance to processes of gentrification and urban renewal, this map shows the distribution of homeless shelters and non-market housing. These areas are gradually being gentrified, and the residents of the Downtown Eastside are living in spaces of resistance. Homeless shelters and non-market housing are acts of resistance because they provide the ability for the residents of the Downtown Eastside with less economic capital to reside there, whereas processes of gentrification and urban renewal have the opposite effect.

Areas like the Oppenheimer district have a greater ability to resist against the power of gentrifiers than surrounding areas do, even with the imposition of names, because of the prevalence of homeless shelters and non-market housing. The physical presence of these points of resistance contribute to the spaces of resistance denoted by our darker blue areas on the map.

Map 3 – Spaces of Exclusivity

In identifying zones of growing economic exclusion, that we operationalize through increases in property value, we have identified several areas that require attention. With respect to areas mentioned in the other sections of our analysis, the area surrounding Strathcona Village, the imagined “East Village”, and the area at the intersection of Jay McInnes’ Crosstown and the official local area of Chinatown (including the site of 105 Keefer) are all notably vulnerable areas through this lens of analysis.

The whole area, compared to its surroundings, suffers from significant property value increase. Before clipping the data to the project area (when it encompassed the three municipal local areas of Downtown, Strathcona, and Grandview-Woodland), it was evident that property value increases were far more intense, generally, in the Downtown Eastside than in the rest of Downtown Vancouver. Grandview-Woodland’s parcels were largely increasing by 20-30% in property value in the past year, similar to the central part of our study area, south of Hastings Street.

Synthesizing remarks

The maps that we created display the reality of gentrification on the DTES and surrounding areas, in three different ways. Through these three lenses of analysis, we identify three areas of particular significance, as they exhibit vulnerability to the exclusionary processes of gentrification in more than one way.

The first is is the intersection between Crosstown and Chinatown, which is visible in all three of our maps. Through the imposition of Crosstown, a new place-name lacking historical background, this section of Chinatown is subject to assertions of power, identity, branding, and commodification. Crosstown-Chinatown benefits relatively less from the ability of non-market housing and homeless shelters to retain an original community than the areas directly north of it, where these services are concentrated.

Surrounding the Strathcona Village development is a zone of the most significant property value increases in the project area. Since this area is also notably distant from concentrations of homeless shelters and non-market housing, we identify this as an area of interest. East Village is a similarly alarming area, because of significant property value increases in the past year, and its lack of proximity to spaces of resistance.

Error and Uncertainty

Our primary source of uncertainty results from how we have sourced our data relative to how these spaces are truly experienced, conceptualized, and lived by the people who occupy them. Boundaries, in our project scope of neighbourhood and colloquial areas, are socially constructed. We relied upon boundaries that were delineated on policy documents, in the municipal data catalogue, and property development websites, but it is difficult to affirm that the place-names that we have used in our analysis of overlapping toponymy are the most appropriate, and that their boundaries reflect the perception of those who acknowledge those spaces. In selecting these few, we may have missed collective spatial conceptualisations of local residents, and thus we would have missed the opportunity to identify a process of identity erasure of a neighbourhood. Our selection of 105 Keefer and Strathcona Village as two key developments to identify on our maps, while they are both prominent in how they have produced local controversy and how they impose identities through place names, is somewhat arbitrary. A more rigorous approach to deciding to include or exclude key developments form these maps would have been more conducive to analyses with respect to effects on gentrification.

It is important to note that our maps cannot be used to imply causation between the placement of new developments and property value increase. It would be misleading to suggest that the Strathcona Village development is an area exhibiting property value increase – and the resultant displacement of previous residents – for the sole reason of being situated in an area of 40% property value increases. Further research into the lived experiences of area residents, and economic processes in the area are recommended.

Drawing conclusions from the Spaces of Economic Exclusion map that increasing property values, by default, result in exclusion of the local population are unfounded. While this is generally the pattern described by the concept of gentrification, this claim would have to be confirmed in context as well. Finally, the small scale of our maps creates a lack of a basis of comparison; we are unable to assert that the degree of property value increase is, indeed, remarkable to local circumstances.

Further Research and Recommendations

In this project, we have identified areas of the Downtown Eastside that are particularly vulnerable to the processes of gentrification that we have outlined in this report. Namely, the areas for future study and action are the blocks that constitute the intersection of Crosstown and Chinatown, the northeast corner of Strathcona surrounding the new development of Strathcona Village, and the northwestern corner of Grandview-Woodland that is indicated in this project as “East Village.” Investigating the processes of gentrification to confirm the causal relationships our maps gesture towards in these areas, and providing services that can protect local residents and their right to their neighbourhood, is our suggested course of action.

The generation of primary sources, through interviews and focus groups into the processes of development and the lived experience of residents, can serve to validate the processes of erasure and exclusion that we suspect may take place in the specific areas we have outlined. Continuing research for how these boundaries are constructed and lived in these areas may be useful in continuing this study of the dynamics of toponymy in the Downtown Eastside. Employing these research methods to identify what other spaces are meaningful to the identities and livelihoods of local residents can contribute to an improvement of the conceptualisation of “spaces of resistance.” Seeking these data will provide the foundation for rigorous analyses and the clear identification of which spaces and processes in the Downtown Eastside contribute to the perpetuation of exclusion, and which contribute to the protection of local residents and their right housing and the definition of their neighbourhoods.

Appendices

Bibliography

Please excuse the formatting issues!

Cahill, C. (2006). “At Risk”? The Fed Up Honeys Re-Present the Gentrification of the Lower East Side. Women’s Studies Quarterly,34(1/2), 334-363.

City of Vancouver. (2012). Downtown Eastside Local Area Profile. 34.

City of Vancouver. (2015). Downtown Eastside Local Area Plan.

Mackie, J. M. (2016, May 03). Controversial project in Vancouver’s Chinatown revised.

Retrieved April 10, 2017, from

http://vancouversun.com/news/local-news/controversial-project-in-vancouvers-chinatown-revised

McInnes, J. Downtown, Vancouver, Real Estate Website by Ubertor.com. (2011, July 27).

CrosstownCondos.com. Retrieved April 15, 2017, from

http://www.crosstowncondos.com/Blog.php/category/What is Crosstown Vancouver%3F/18

Neighbourhood. (n.d.). Retrieved April 04, 2017, from http://strathconavillage.com/neighbourhood/

Phares, M. (2013). A case for public interest design in vancouver’s downtown eastside

Ruddick, S. (1996). Constructing difference in public spaces: Race, class, and gender as interlocking systems. Urban Geography 17(2), 132-151.

St. Denis, J. (2017, January 10). Even with changes, condo not welcome on important Chinatown site, says group | Metro Vancouver. Retrieved April 09, 2017, from http://www.metronews.ca/news/vancouver/2017/01/11/condo-not-welcome-on-important-chinatown-site.html

Rose-Redwood, R., Alderman, D. (2011). “Critical Interventions in Political Toponymy,” ACME: An International E-Jornal for Critical Geographies 10(1): 1-6.

Rose-Redwood, R. (2011), “Rethinking the Agenda of the ‘New’ Political Toponymy,” ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 10(1): 34-41.

Vancouver School Board (n.d.). Crosstown Elementary. Retrieved Retrieved March 27, 2017,from http://www.vsb.bc.ca/crosstown

Wideman, T. J. (2015). (Re)assembling “Japantown”: A critical toponymy of planning and resistance in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Queen’s University Press, ii-12.