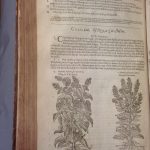

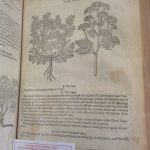

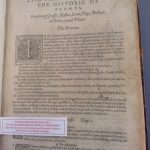

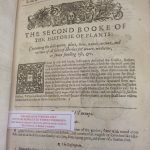

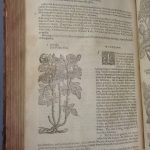

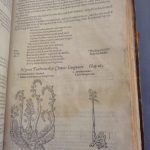

These are some good examples of the attempts at organization and nomenclature of plants at a time when there really was no classification system in place (Knight 66-67). Thus, the names are sometimes quite poetic and imaginative (66-67). On the more mystical plants in his Herball, Gerard was actually aware that plants such as the “mandrake” had a fantastical history and he stated so in his account of such plants (108). According to Knight, he may have included them to highlight the way botanists doing “scholarly writing” would sometimes simply copy ancient texts verbatim, regardless of outdated information (108).

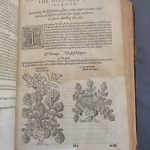

- Close-up of the “stonie wood” (1597 edition).

- Debunking myths of the Mandrake root (1633 edition).

- Qualities, location and virtues of the Mandrake (1633 edition).

- More Mandrake myth-busting (1633 edition).

- “Nep, or Cat Mint.” Cat-nip used to be called “Cat Mint!” (1633 edition)

- Virtues and naming of Cat Mint (1633 edition).

- “Of Stinking Carrots” (1633 edition).

- “Of Stinking Carrots: Subgroup, Deadly Carrots” (1633 edition).

- “Muscus ex cranio humano,” or “Moss growing on the skull of man.” (1633 edition)

- “Muscus ex cranio humano,” or “Moss growing on the skull of man.” Close-up, 1633 edition.

Works Cited

Knight, Leah. Of Books and Botany in Early Modern England: Sixteenth-Century Plants and Print Culture. Surrey, Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2009.