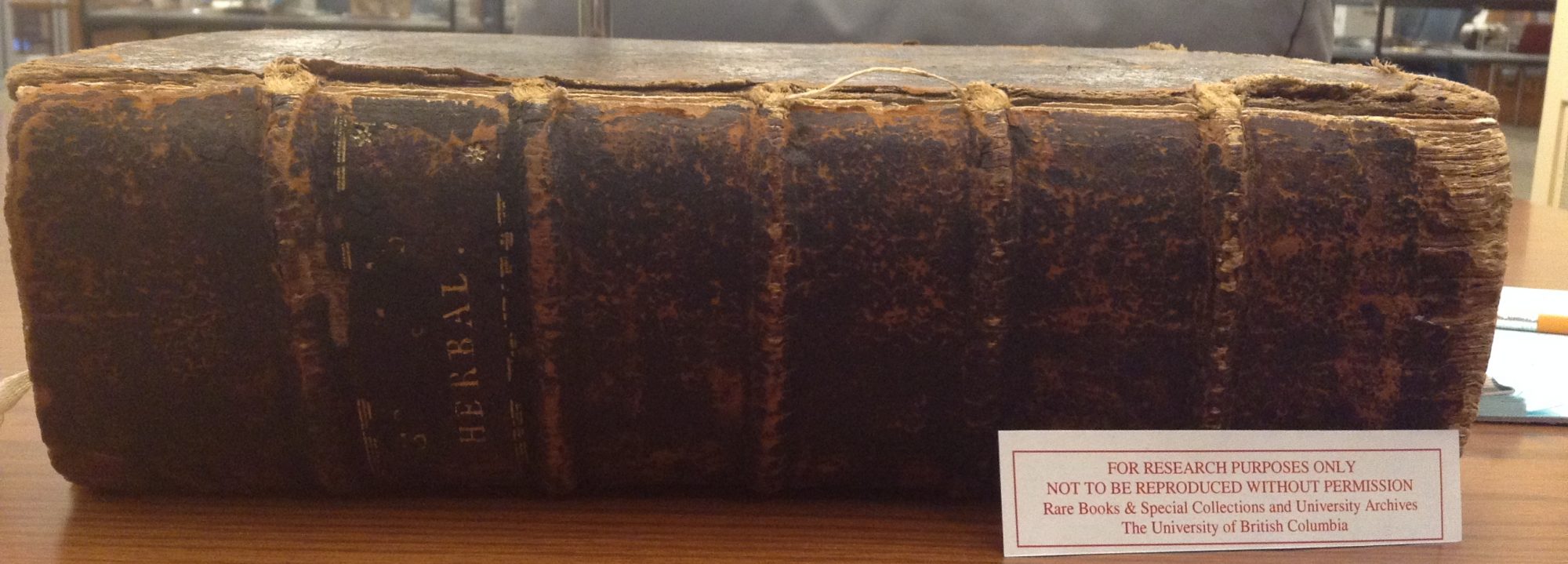

John Gerard (1545-1612) was an English surgeon, author and herbalist, most famous for publishing The Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes (“John Gerard”). Gerard’s book enjoyed widespread popularity in its day, continues to be published in the present, but the reason why Gerard initially became popular cannot be provided with absolute certainty. He studied to be a surgeon, and while completing his apprenticeship in London under the surgeon Alexander Mason he developed an interest in gardening (“John Gerard”). Note that at this time, a surgeon was considered a trade: Gerard did not attend university, and he was not an M.D. (Leah Knight, “Of Books and Botany” 70). He was appointed superintendent to the gardens of Lord Burleigh (that is, William Cecil Burleigh) (Paul Cox , “The Promise of Gerard’s Herball: New Drugs from Old Books” 51) and Theobald House (Arthur Hollman, “A History of the Gardens of the Royal College of Physicians in London” 242). According to Cox, he was later appointed to be the curator of the Physic Garden of the College of Physicians in London (51), but a search of the history of this garden reveals only that the follow-through of Gerard’s appointment is vague and the very existence of the College’s garden is questionable, as there are no records of it being planted (Hollman 242). There is, however, a written record of Gerard’s personal garden in Holborn, London, compiled by Gerard himself and published in 1596 (“John Gerard;” Cox 51), and titled “A Catalogue of the Plants Cultivated in the Garden of John Gerard in the Years 1596-1599.”

It may not be Gerard who was popular, but rather the genre of herbals themselves. Across Europe during the 16th century, there was a newfound interest in the medicinal properties and identification of plants (Brent Elliot, “The World of The Renaissance Herbal” 24; Cox 51). Gerard published his work at a time when herbals were very popular; his work was extremely comprehensive, cataloging plants according to the botanical lexicon of the time for describing plant anatomy and paying attention to relevant details such as where the plants were found (Elliot 26-27). Gerard’s work is described as unsurpassed with respect to its detail and the volume of information (Elliot 26; Cox 51). There was a lot of “borrowing” between authors and illustrators happening at this time: Gerard was accused of plagiarizing Stirpium Historice Perptades Sex, a herbal written by Flemish botanist Rembert Dodoens (1516-1585) and published in 1583 (Cox 52). This accusation was not hostile, however, as information concerning plants at this time was largely shared and reused between herbalists, whether through personal communications or research (52). Gerard’s plagiarism really was “borrowing” just as botanists before him had borrowed information from other botanists and so on (52). Quite literally, “all was fair in plants and printing,” but in a communal sense, where copying was regarded more as “sharing” since most of the plants were already known, their histories were just being re-examined (Cox 52; Elliot 24). For more information on the sharing and borrowing of botanical knowledge see “All if Fair in Plants and Printing 2.0.” For more on the controversial allegations of plagiarism against Gerard, see “All is Fair in Plants and Printing 3.0.”

-

-

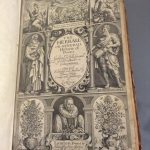

Book plate (engraving) by John Cook in 1633 edition of the Herball; also reprinted in 1636 edition.

Works Cited

Cox, Paul. “The Promise of Gerard’s Herball: New Drugs from Old Books.” Endeavour, vol. 22, no. 2, 1998, pp. 51-53, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-9327(98)01111-9. Accessed 20 March 2018.

Elliot, Brent. “The World of The Renaissance Herbal.” Renaissance Studies, vol. 25, no. 1, 2011, pp. 24-41, doi: 10.1111/j.1477-4658.2010.00706.x. Accessed 13 April 2018.

Hollman, Arthur. “A History of the Gardens of the Royal College of Physicians in London.” Clinical Medicine, vol. 9, no. 3, 2009, pp. 242-246, http://www.clinmed.rcpjournal.org/content/9/3/242.full.pdf+html. Accessed 15 April 2018.

“John Gerard.” Encyclopædia Britannia, 26 July 2015, https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Gerard. Accessed 15 April 2018.

Knight, Leah. Of Books and Botany in Early Modern England: Sixteenth-Century Plants and Print Culture. Surrey, Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2009.