3.7 – Hyperlinking the Text

GGRW start “Dr. Joseph Hovaugh sat at his desk … [12] End: “What happened to the Trees …. Yes, said Robinson Crusoe ….” [18]

My assigned section interwove between multiple storylines, as much of the story does, and posed some interesting dichotomies between characters. I’ve gone through and analyzed the main and most important ones in order to draw connections that can lead to better understanding.

Dr. Joseph Hovaugh – As Flick notes, the name is a play on Jehovah. The parallel is between King’s character and God in the Bible. In the opening scene of my pages, he “seemed to shrink behind the desk as though it were growing, slowly and imperceptibly enveloping the man” (King 11). Before this the text reveals a parallelism between the two in Genesis 1:31 — “And God saw everything he had made and, behold, it was very good” — and page 10 — Dr. Hovaugh sat in his chair… and he was pleased.” The desk behind which he sits is taken from the physically created world, and, like God, the thing he made is the thing that eventually grows to both envelop him and push him away.

Alberta Frank – One of the many names with inference, the “frankness” of her character is represented in the character herself as well as the province her name mimics. This trait is shown in Alberta’s response to Mary’s question of what will happen if they don’t spell the names right on the test: “You probably won’t get exactly all the points.”

Lone Ranger – A fictional character from American history, the Lone Ranger was a cowboy who fought American outlaws. Political Blindspot claimed the fictional character to be based off a man named Bass Reeves, who lived a pretty crazy post-Civil War life. Many details of the Bass Reeves’ life are similar to that of the Lone Ranger: “a lawman hunting bad guys, accompanied by a Native American, riding on a white horse, and with a silver trademark.”

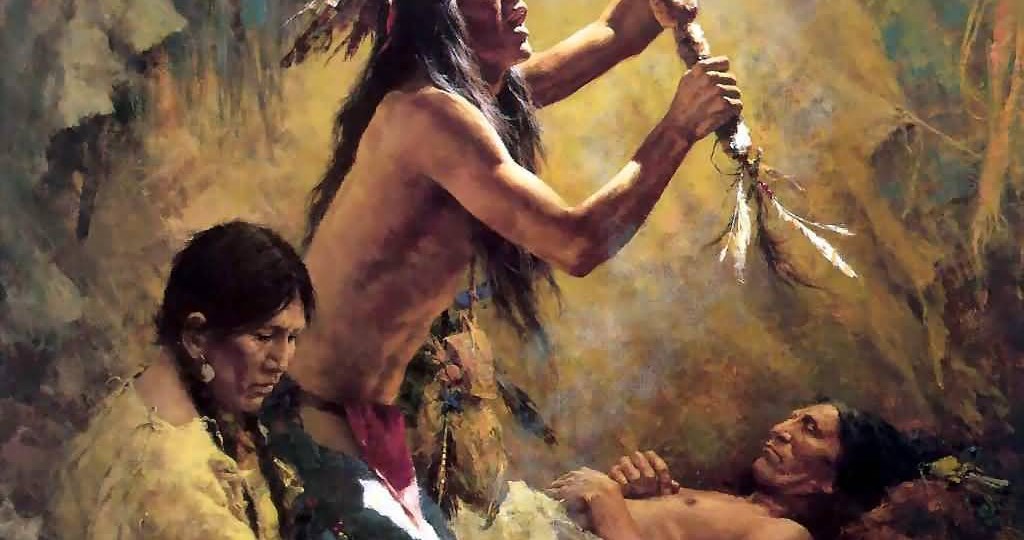

Hawkeye – A longstanding historic Native character and name, Hawkeye’s Canadian literary history goes back as far as 1826. In James Feminore Cooper’s novel The Last of the Mohicans, he is a “is a fearless warrior who carries a long rifle and wanders across the frontier.”

Robinson Crusoe – Based off the real-life shipwrecked mariner Alexander Selkirk, King’s Crusoe symbolizes the sense of survival within the story. “It is a beautiful sky, however,” reveals Crusoe’s ability to make the best of a situation, a survival-based necessity (13).

Ishmael – Ishmael is a character with biblical and literary implications. The name therefore brings implications from Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, the story of Genesis in the Bible, and other creative adaptations.

Works Cited

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass Running Water.” Canadian Literature 161-162. (1999). Web. April 04/2013.

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. Toronto: Harper Collins, 1993. Print.