1.3 – Humility on Common Ground

At the heart of the intersection between story and literature we will easily find the meeting of native and newcomer, and as Chamberlin says, “I keep returning to the experience of aboriginal peoples because it seems to me to provide a lesson for us all. And for all its [Canada] much-vaunted reputation as an international mediator and peacemaker, it is in this story of natives and newcomers that Canada really has something to offer the world” (228). And, then he goes on to propose: “Why not change underlying title back to aboriginal title?” (229). Explain how Chamberlin justifies this proposal.

Chamberlin’s stories are seemingly endless. The creativity with which he approaches ideas previously unquestioned results in perspectives and understandings otherwise left misunderstood or worse, not contemplated or considered at all. The importance is on not only the stories he writes and their validity, but all stories. The truth of the stories, as he asserts multiple times throughout the novel, is two-fold. It is both real and not real. The stories happened and they didn’t. This understanding is what allows Chamberlin to provoke the argument of changing “underlying title back to aboriginal title.” It is this shift in perspective on which the argument stands.

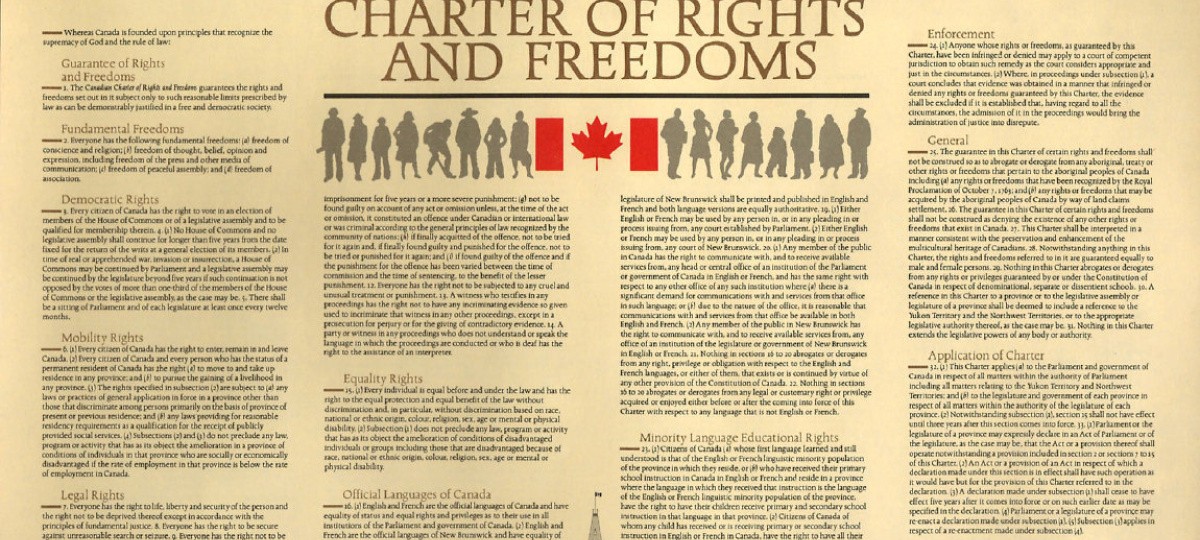

Canadian understanding of claim and title is based largely upon definitive legislation that leaves no room for the interpretation of stories. Sure, it’s a good thing to be definitive in terms of “equal treatment before and under the law, and equal protection and benefit of the law without discrimination” but the legality leaves out a component of understanding and rather proposes one of entitlement (Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms).

Chamberlin makes his case simple, he wishes “to give the reader a sense of how important it is to come together in a new understanding of power and the paradox of stories” (239). He warns that the Them and Us mentality is inevitable but that, rather than a choice between one or the other, we should take the stance that, like the validity and truth of stories, coexistence is possible. The physical common ground we share can be more beneficial if understanding is met on both sides of the story. Changing underlying title back to aboriginal title allows the first peoples to keep what is important to them while not sacrificing what is important to the settlers. It is a win-win situation and the only price to pay is the smallest amount of humility and understanding. Not a bad ROI if you ask me.

Works Cited

Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, s 2, Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11. Web.

Chamberlin, J. Edward. If This Is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories?: Finding Common Ground. Toronto: A.A. Knopf Canada, 2003. Print.