Breakfast for me is the most important meal of the day, which in a way makes it the most important meal for measuring oil because I religiously eat the exact same breakfast every day. My breakfast virtually always consists of 2 eggs, fried or scrambled, with 2 pieces of toast with margarine. Very occasionally my parents will have bought breakfast sausages or bacon and I will have a few, but most of the time (as well as Wednesday, which was when I recorded my food consumption) it’s just eggs and toast.

Eggs

The brand of eggs that my parents buy is called Nature Egg Omega 3. I called their company office in Calgary to find out more information on how the eggs arrive to Victoria, where I live. The receptionist told me that most of the eggs that are shipped to the island come from their closest farm in Alberta. However, she also said that the special omega 3 brand that my parents buy, which feeds the chicken a special flaxseed diet for better nutrition in eggs, probably has come from their production facilities in Winnipeg.

As I dug deeper on their website, I found exactly what I was looking for- a “from the farm to your table” page, outline every step of the process from what I am assuming is from their farm in Springstein, Manitoba to Victoria, BC. Their comprehensive flowchart can be found here[1], but I will briefly touch on the steps myself and try to come up with a rough quantitative value for the oil used where I can.

The areas where fossil fuels were used are as follows:

1. On the Farm: The chickens making omega 3 eggs are fed on a diet that consists largely of flaxseed and other grains. These grains are not only very likely to have been grown with fossil fuels[2], but also had to be transported from the flaxseed farm, probably by truck, to the chicken farm in Springstein.

2. The eggs are stored in a refrigerated storage room before being transported. Like BC, most of manitoba’s power is hydroelectric, so this would have a relatively low oil consumption

3. The eggs are transported from the farm to the grading station. From what I could understand from talking on the phone to Burnbrae farms, the grading plant that processes the Manitoba eggs is likely in Winnipeg, which is roughly an hour drive away in a refrigerated truck from the farm at Springstein.

4. The eggs go through a grading process, which involves cleaning, inspecting, weighing, stamping and packaging the eggs into cartons. His process is now entirely mechanized, so it seems to be a high energy process. It also is important to note that while much of this energy may be hydroelectric, the energy that was used to produce the egg cartons could have a much higher carbon footprint if it was made outside Manitoba.

5. after being packaged and stored in another cooling room, they are taken by refrigerated truck to the supermarket. The distance from Winnipeg to Vancouver is roughly 2294 km. As I was fortunate enough to read on Jon’s food blog[3], he cited that Natural Resources Canada put the average fuel consumption for trucks in 2000 was 39.5/100km[4], although I would suspect that that number may be lower today due to increases in fuel efficiency. By the averages of the year 2000, the amount of fuel used to drive from Winnipeg to Vancouver would be roughly 90,613 litres. That number would have to be divided by the number of eggs were actually in the truck to get the average amount of oil that we could assign to 2 eggs.

6. the eggs then stay in the refrigerator of the supermarket until my parents use fuel to drive to the Thrifty Foods that is 10 minutes away from our house, purchase the eggs, and then drive back. This entire process takes around 6-10 days.

Interestingly, I stumbled across Burnbrae Farms Social Responsibility where they assert that their focus is on preserving the environment. They currently have an employee energy awareness program in place that aims to reduce the energy consumption of their farms by 3% over the next year, although they do not say when this was implemented and when the deadline will be. They also have waste management and wildlife preservation programs, which includes them designating 1100 acres of wood for wildlife habitat and planted 2,500 trees in “three years”(again it does not specify when those years were).

Toast

The toast I ate was called stone milled 100% whole wheat from country harvest. Given that it is a Canadian company and that its main ingredient is flour, I would assume that it comes from somewhere inside Canada, probably somewhere on the prairies, which means it is at least 1000 km away from Victoria. The packaging is plastic, which takes fossil fuels to create. Given that the packaging for bread is similar to a plastic grocery bag, I will assume its weight and fuel intake for production is the same. The average plastic bag is 5.5 grams[5], and it takes 1.26 kg of oil and natural gas and 48 Mejajoules of energy (which is roughly equivalent to one litre of oil) to produce one kg of plastic bags[6]. This is difficult to quantify for only one bag in a 24 hour period, but using these numbers a rough estimate for plastic production of bread could be calculated for a year.

Its also important to note that energy was used to power my toaster to toast the bread; however, given that I live in BC, most of my electricity is hydroelectric.

Orange Juice

The juice I drank yesterday is from Tropicana. Tropicana buys and processes all of their oranges from Florida, and then ships it around the world. When looking at the video above from the Tropicana website, I was interested to learn a few things that hadn’t occurred to me before. The first thing was that all of their orange juice is pasteurized for health reasons when shipping. This is another step in the long and complex processing of the juice, coordinated by computer and human supervision.

The other thing that interested me was that given that Tropicana OJ is demanded year round, the company makes extra juice and stores it under refrigeration. The harvesting season for juice oranges generally ranges from December to march[7]. The interesting aspect of this is that depending on what time of year it is, the juice may have a different fossil fuel receipt to it. I was aware of this idea already, but the interesting part is when I realized that in this case, that wasn’t because the fruit was being shipped from a warmer place, but more that due to the growing season, fruit coming from the same place takes up fuel to be refrigerated in the off season.

After the processing, the Tropicana that I drank was transported to where I live, with a combination of truck, rail and ferry travel. Tropicana insinuates that much of its transportation is done by rail, which it purports is three times more energy efficient than moving it by truck. I know that it travels by truck at least part of the way, given that I live on an island, and that it had to cross over on the ferry at some point. I would think that given its distance, as well as the processing involved and the fact that the orange is out of season, makes this ingredient the most carbon intensive of the meal.

Margarine/canola oil

Canola Production In Canada

74% is of Becel margarine is made up of canola oil, so I will assume that is the most Significant ingredient in terms of fuel contribution. The canola oil that I used for frying my egg is Crisco oil, which says that it uses only Canadian seed as its input. The overwhelming majority of Canadian canola crops are located in Saskatchewan, Alberta, and Manitoba, but there is a tiny amount of canola production in hope, BC as well. However this BC production also has to move through processing plants in Alberta, so it is safe to say that at the very least the canola has travelled 1000 km by truck to Victoria, and possibly twice that amount if it has been harvested in Manitoba.

When thinking about the oil burned to grow my canola crop, I initially thought of the fertilizer to grow them and the tractors to harvest them. But here are some other inputs that I read from the BC ministry of Agriculture website that I didn’t consider[8];

Shipping the pesticides to the farms, fuel for crop dusting planes, the fossil fuel it takes to keep the human farmers alive and well to tend to their crops (the cycle continues) inspectors driving to the farns to inspect grain, and the fossil fuels burned that are assosicated with the commercial aspect of the process- ie. “selling” the crop.

The production of canola seed into canola oil has many steps, and from looking at the video below, is a highly energy intensive process.

How Its made- Canola Oil

Whew! Only one meal took me hours to research and speculate on. I think for the next two meals I will be more general in my descriptions in where my food came from. All this work has made me hungry, so I think il make myself a snack. Thankfully my measurements are based off of Wednesdays food intake- otherwise I would be scared to eat more in fear of making more work for myself!

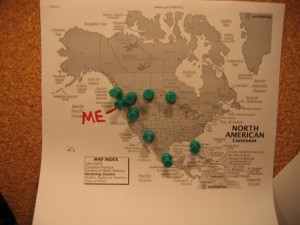

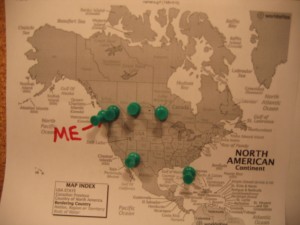

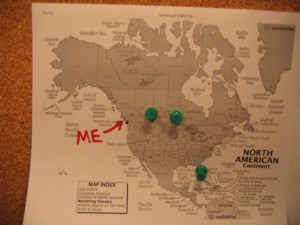

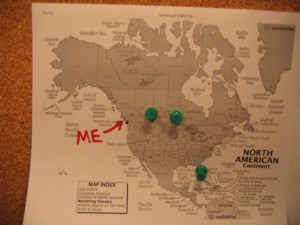

Here is a map of everywhere that my food came from:

So far my food intake hasn’t been too bad, at least in comparison to what I fear may be in store for the next meals. I’ve managed to stay basically in North America so far, with the farthest transportation being for oranges from Florida. Lunch and dinner to come!

[1] Burbrae Farms, “Farm to Table”, http://www.burnbraefarms.com/ourfarmers/farm_table.htm

[2] Flax Council of Canada, “Growing Flax”, http://www.flaxcouncil.ca/english/index.jsp?p=growing3&mp=growing

[3] Jon’s 24-Hour Consumption Blog, “Jon’s Breakfast” https://blogs.ubc.ca/jonsfood/

[4] Office of Energy Efficieny, “Results of an Industry Survey, http://oee.nrcan.gc.ca/publications/transportation/10771

[7] page 3 http://citrusmh.ifas.ufl.edu/pdf/db/Whitney87ASAEv3p20.pdf