Last time, I took an in depth analysis on critical thinking, using examples from my experiences as an athlete. Additionally, I briefly mentioned System 1 & 2 thinking, and stoic philosophy. The previous blog on Critical Thinking had too many ideas and as I re-read it, I realized that it was quite confusing and for that I apologize. I hope this time will be better.

I am still practicing stoic philosophy as much as I can, applying it to all parts of my life. It has worked very well for me and I would like to say it has turned me from a Type A into a Type B personality. Recently, I found out that Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) has some philosophical roots from stoicism. Perhaps I will dive into some more CBT in the future.

In my personal opinion, stoicism is a way to think about things in a reasonable way, and often times critically. Sometimes things may frustrate me, and I notice that. With stoic thinking, I ask myself if what I’m frustrated about is within my control. If it is, then I have the ability to make the change. If not, I simply realize that the situation is beyond my control, and that being frustrated will do me no further benefit. Taking stoicism into sport has been quite interesting, and my approach as both an athlete and coach have shifted. I no longer feel the need to be pumped up to play, and keeping very calm is sometimes good for the athletes I coach. As I am in control of myself when I compete, I can adjust arousal levels as necessary. However, as a coach, what an athlete does is outside of my control. Because of that, I put a lot of the accountability back on the athlete, and I remind him/her that I am only a tool to help them, not a crutch. I prefer to give my athletes quiet confidence, instead of being ‘fired up’ and energetic as a coach. However, I am indifferent in how they choose to play, or how other coaches choose to coach.

“You have your way. I have my way. As for the right way, the correct way, and the only way, it does not exist.” – Friedrich Nietzsche

Lately, I decided that I would venture into something different and quite foreign to me. I wanted to be a beginner again, because I have some formulas for success (e.g. deliberate practice, grit, growth mindset), and I have spent some time ‘learning how to learn’. One of the reasons why I am doing this is so that I can have a taste of what a beginner feels again, and understanding how to approach problems from their perspective…yes, critical thinking brought me here. Currently, I am trying to learn Python, a programming language, in an attempt to get a taste for data science. Although the term “data science” is quite broad, I feel that I’m at such a beginner stage it makes little difference at the moment. Perhaps I will specialize in something else one day, or I may even give up on this pursuit eventually. I’m just taking it one day at a time.

After completing my first Python course online, I am already on a second course and trying to do refresher courses on Statistics and Calculus. In addition to learning Linear Algebra in the near future, there is a lot more to do, and often times I’m uncertain which direction I’m going in. As a beginner, it’s easy to get overwhelmed, but there are so many resources available including friendly people that will help you out if you ask them nicely. But I do understand it can be difficult to talk to people sometimes, so as a high level badminton player and developing coach, I try to approach those who could use a hand who may not be able to ask for help yet in badminton. Most of the time, people are more than happy to get some tips and then we can continue to connect in the future. Fortunately for myself, there are a few badminton players who have extensive computer science backgrounds, so it’s definitely win-win with the information exchange.

There is also another reason for learning data science, and after watching the movie Moneyball, it only strengthens my desire to see how I can implement data analytics into my sport. I could wait for our association to hire a data scientist, but I’m willing to wager that I can probably become one myself before that happens. Perhaps I might get hired for that hypothetical job, but one can only dream. Thinking critically has given me a question that I cannot answer at the moment: how accurate are our perceptions of the game? Feeling and perceiving is one thing, but having the evidence through data analytics can give us an honest answer. Much like video analysis gives us insights on how we look like when we perform, there are times when what we perceive as our performance is far different that what the camera captures. By accumulating and analyzing data, perhaps we can get better insights based on data instead of our own experiences. At the very least, a comparison between the two would be nice.

Although I am currently working on my Gold Medal Profile (GMP) for Dr. Van Neutegem’s class, I never believed in the concept when I first heard it from our High Performance Director at the time. It didn’t really make much sense to me when he explained it to the athletes, and I felt there was very little buy in. Although his level of depth into the area was limited as well, Badminton Canada hired Dr. Van Neutegem for consultation purposes. Perhaps it was a bit of fate that I ended up in this program and having him as a professor, but I say that with gratitude as this coaching program has changed me for the better, as both athlete and coach. After hearing and seeing examples from Dr. Van Neutegem in class, I was much more convinced. However, I still have a bit of difficulty when talking to other coaches and athletes about the concept, although I am starting to get a bit of buy in from them. To be honest, I still have some doubts because of the difficulty in figuring out what to measure. And to be fair, I believe each coach has their own “GMP” in their minds, and that would bring us back to Nietzsche’s quote from above.

For example, I heard that we want to know the consistency a player can hit a certain shot, as a technical parameter. But when I critically think about the problem, it doesn’t make sense because in non-competition conditions, there is little pressure to execute. Considering that heart rate is usually quite higher in competition conditions vs. training conditions, how can we measure someone’s consistency under pressure? Additionally, even if a player’s consistency is less, it can depend on their ability to win rallies. Maybe greater risk gives greater reward. So, how can we measure such parameters?

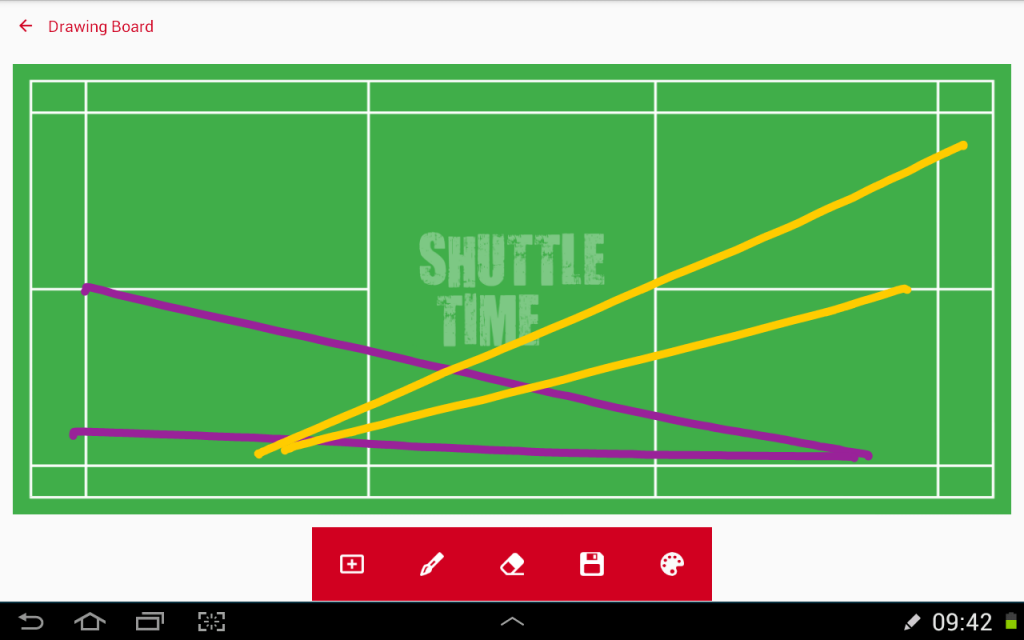

As I have said before, I believe critical thinking and problem solving often come together. I believe data analytics will give much better measurements, and finding a way to measure things better will give us better insights in the future. I think the same goes for anything else, including health, business, and many other aspects of life. Perhaps I’ve been bitten by the “big data” bug. After watching the movie Moneyball, I often wonder if it’s a race to figure out the best way to measure badminton data. After looking into the possibilities of data science, it feels like it’s only a matter of time. However, at the moment, there is a lot of “noise”, which may prevent us from finding the “signal” (see Nate Silver’s book: “The Signal and the Noise”, on my reading list). There are many things that happen in a badminton match, but figuring out what is really important is only debatable at the moment. Athletes, coaches, and other staff are often biased by their backgrounds in what they see, but I think big data can find correlations and trends that we fail to notice when we rely on memory. For example, I was coaching a match and I simply had a badminton court and would mark where one player hit successful smashes, and where they lost on smashes from their opponent. To my surprise, one player won more smashes on her opponent’s backhand side, while she lost on her forehand side. At the interval, she was able to adjust slightly based on the data provided.

From BWF Shuttle Time App

So here lies the problem to solve: how do I create a GMP? From stoic philosophy, each obstacle provides an opportunity. Not knowing what to do for a GMP means it becomes an opportunity to find out. Every hurdle is a problem to be solved, sometimes with an easy answer, sometimes not. Critical thinking is required every step of the way, often asking different questions: WHAT do I need to do? HOW do I do it? WHY do I choose this path? Learning Python (WHAT) is part of the process because there are powerful analytic tools that will be useful in the future (WHY), and learning online (HOW) is the opportunity as it is self-paced. I often get stuck, which is an obstacle in itself, but it as an opportunity to problem solve and learn more. It’s an opportunity to feel like a beginner again, and it helps me to better understand the process and related to beginner badminton players when I’m coaching.

The obstacle is still the way…