Figure 1. source: https://www.csf.bc.ca/wp-content/themes/csf/img/logo.svg

VISION: All our students will reach their full potential, taking pride in their French language and Francophone culture. MISSION: To develop in our students, from an early age, proficiency in the French language, a culture of life-long learning, a healthy lifestyle, and a desire to contribute to society.

Brainstorm

In this task, we were each given the role of a technologist and assigned groups with a given case to create a rubric. The rubric will direct the decision making of determining which Learning Management System (LMS) will be selected for a specific context. In our case, we looked at, Le Conseil scolaire francophone de la Colombie-Britannique and their partnership with LearnNowBC. Their aim is to deliver online secondary education to adult French language speakers.

As an educator first, we often place the needs of the student before our own, creating a student-centred environment. A useful framework I often use when looking at learning environments is by Bransford, Brown, and Cocking (1999), which looks at how people learn. They argue for an environment that is student-centred, knowledge-centred, assessment-centred, and community-centred. Anderson (2008) makes a suggested revision for online environments in which student-centred is replaced with learning-centred. In this environment, the needs of the learner, institution and the community are negotiated as well. I envisioned placing each one as its own category in our rubric. Within each category, there would be two to three criteria items. For example, for the category, community-centred, a possible criteria would look at how student-student interactions and student-community interactions could be facilitated. Since an LMS can be seen as a tool, the criteria will focus on how the LMS supports the design of such interactions. Imagine yourself talking to a salesperson and asking the right questions, these would be in the criteria items.

I may have been confused by the expectations of the assignment, and was moved in a totally different direction after reading the clarifications and group discussions. A larger emphasis needed to be placed on the course readings. I then focused my attention on Bates’ SECTIONS model (2014) for selecting technology. He proposes each letter from SECTIONS as a category and each letter stands for:

- S tudents

- E ase of use

- C ost

- T eaching functions, including pedagogical affordances of media

- I nteraction

- O rganizational issues

- N etworking and Novelty

- S peed and security

The group as a whole voted against using each letter in the model as categories for our rubric. This decision was critical and negotiated heavily. The ultimate deciding factor was due to a presented sample rubric by Lauren Anstey & Gavan Watson from Western University, Canada.

Starting from an already created rubric introduced new dynamics. We were now in a role of evaluating a rubric. In this evaluation we discussed many different frameworks on which the rubric was built from and gave each other plenty of readings to do. Members were able to connect their prior knowledge and present it to one another. This led to rapid learning occurring.

Evaluation of Rubric

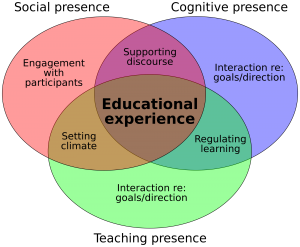

Figure 2. Community of Inquiry Model source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e7/Community_of_inquiry_model.svg/2000px-Community_of_inquiry_model.svg.png

I was able to understand some of the variables involved in online learning. We founded our rubric on the community of inquiry model which was a Canadian project that looks at the educational experience of an online learner as meeting the intersection of social presence, cognitive presence, and teaching presence (Garrison & Vaughan, 2008). We took each one of these to represent a separate category in the rubric and then added the criteria based on our contextual needs. Given the mission of the school to develop learners that will contribute society. We needed to be sure that our LMS will be able to support them and have included them throughout the three initial categories. These include the ability to network, collaborate, and experiential learning. We made sure that the mission of the institution lined up with the technology as suggested by Bates & Sangra (2011) in planning and managing online learning. This resulted an emphasis in the cognitive presence category, where we emphasized the criteria that will allow for experiential learning that can connect learners to the real world. This will enable learners to join communities of practice and develop and nurture their passion in life-long learning.

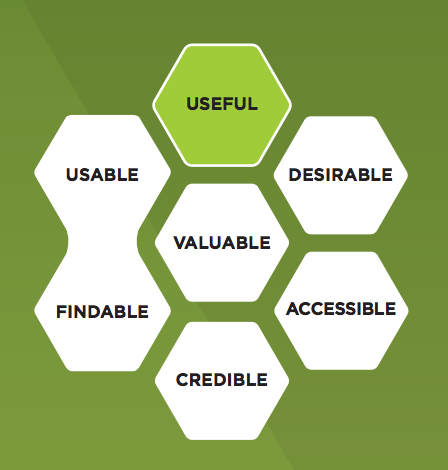

Figure 3. User Experience Design for Learning by University of Waterloo is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Recognizing that we were addressing the needs of adult learners who did not complete high school, we made sure that they will have to feel supported, and motivated in the navigation of the LMS tool itself. In other words the interactions: teacher-content interface; student-teacher; student-content; student-content interface; student-teacher; teacher-content; and content-content (Anderson, 2008). Simply put, the interactive design (UX) of the LMS tool. These led us to include more categories into our rubric: functionality, accessibility, technical, usage, inclusivity. These categories were created after finding more details about UX specific for online learning. We referred to the UX honeycomb, User Experience Design for Learning (UXDL) from the Centre of Extended Learning by the University of Waterloo, Canada. Within these design principles the needs of adult learners will be at the forefront but also the needs of the teachers. Some of the key ideas from the honeycomb model:

- present words with pictures than with words alone

- technology is lined up with web content accessibility guidelines (WCAG 2)

- a clear pedagogical vision without compromising beauty and function

- quality of visual and interaction design

- to create intuitive (usable and findable) learning experiences

Future Recommendations

We felt more confident about our rubric in addressing the needs of the learners and aligning with the mission of the institution. We would have wanted to include more details on the cost constraints but due to insufficient information, left this category out. In future revisions of the rubric, we suggest for adding a category that will influence the selection of the technology within the budget needs of the institution.

Towards a Theory of e-learning

As for my personal growth in this task, I am more confident in recognizing the variables in online learning and appreciate the complexity of their interactions. These interactions and variables are described further in Anderson’s (2008) model, and a visual representation in figure 4.

Figure 4. The variables and interactions in online learning as found in Anderson’s (2008) theory towards e-learning theory

Final Product

Rubric, please click here to download. I will find a way to make it visually appear here at a later time.

Sources:

Anderson, T. (2008). Towards a theory of online learning. In T. Anderson & F. Elloumi (Eds.), Theory and practice of online learning (2nd Edition, pp. 45-74). Athabasca: Athabasca University. Retrieved from http://www.aupress.ca/index.php/books/120146

Anstey, L., & Watson, G. (2016). Rubric for eLearning Tool Evaluation [Scholarly project]. Western Univeristy, available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

Bates, A.W. & Sangra, A. (2011). Managing Technology in Higher Education: Strategies for Transforming Teaching and Learning. San Francisco: Wiley.

Bates, T. (2014). Choosing and using media in education: The SECTIONS model. In Teaching in digital age. Retrieved from https://opentextbc.ca/teachinginadigitalage/part/9-pedagogical-differences-between-media/

The design of learning environments. (1999). In J. D. Bransford, A. L. Brown & R. R. Cocking (Eds.), How people learn: Brain, mind, experience and school. National Academy of Sciences, (1-24). Retrieved from http://cet.usc.edu/resources/teaching_learning/docs/How_People_Learn_6.pdf

Centre of Extended Learning, CEL UX Honeycomb. University of Waterloo. Retrieved September 30, 2016, from http://cel.uwaterloo.ca/honeycomb/index.html

Garrison, D. R., & Vaughan, N. D. (2008). Blended learning in higher education: Framework, principles, and guidelines. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.