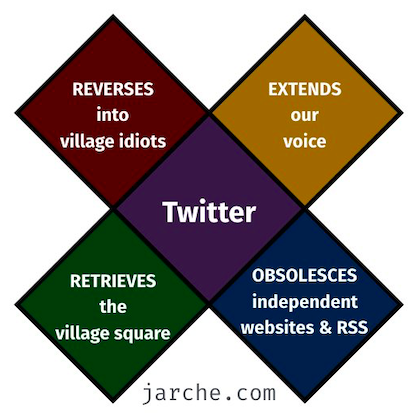

Media ecology, from the Media Ecology Association’s own website, “is the study of media, technology, and communication and how they affect human environments”.

Put another way, it’s a discussion around how media shapes people and society and culture. We’d like to believe that we are, as Seinfeld put it, masters of our own domain; but according to media ecology theory, it’s more that our domains are our masters.

Marshall McLuhan famously said that “the medium is the message”, and that concept speaks directly to media ecology theory. Or put into even more cliché terms, it’s not what you say, but how you say it.

To then bring this into the realm of education and educational media ecology is to take once more the Media Ecology Association’s words: “the study of media, technology, and communication and how they affect human environments” – but we can replace human environments generally, with education specifically.

And certainly it can filter down to more and more specific realms. As an example:

How does the advent of mobile phone technologies affect the high school classroom?

For me in my classroom, I try to encourage the use of mobile phones as much as is possible. Mobile technologies have allowed the instantaneous retrieval of any and all information and as such, they’ve rendered almost obsolete the ability to retrieve information from one’s head. “The meaning of knowing has shifted from being able to remember and repeat information to being able to find and use it” (Bush, pg 14). And in that, course curriculum can (and should) put a greater emphasis on not just what certain information is, but what can be done with it.

_____________________________________________________________________

As ought to have been expected from the article’s title, Strate and Lum didn’t exactly detail their own conceptualization of media ecology, but rather that of Lewis Mumford. Of course they wouldn’t have gone to such lengths to explain Mumford’s thinking had they not themselves been on board; but still. I’d have appreciated an I statement. There’s some facility in standing on the shoulders of giants, as it were.

That said, in Lum’s article, Introduction: The intellectual roots of media ecology he sites Strate’s comments to the Media Ecology Association:

“It is the study of media environments, the idea that technology and techniques, modes of information and codes of communication play a leading role in human affairs. … It is grammar and rhetoric, semiotics and systems theory, the history and the philosophy of technology. It is the postindustrial and the postmodern, and the preliterate and prehistoric. Media ecology is all of these things, and quite a bit more” (pg. 1)

According to Strate and Lum, Mumford laid the base for future media ecology scholarship – a fact that often goes unacknowledged (pg. 56). As such it can well be inferred that Strate and Lum’s own feelings on how to define media ecology are indistinguishable from those of Mumford who “championed planning with regionalism in mind. This meant resisting the drive to megalopolis, [and] implies an ethics in which what takes precedence is life and its drives” (Strate and Lum, pg. 75).

Media ecology speaks to the idea that we should be working within the natural constraints of the medium with which we engage. As Buckminster Fuller said, “Don’t fight forces, use them” (Komlos, 2020).

Strate and Lum champion a reality which values the natural world; whose economy will aim “not to feed more human functions into the machine, but to develop further man’s incalculable potentialities for self-actualization and self-transcendence” (Strate and Lum, pg. 75).

Media ecology will then lead to people working not exclusively to continue the drudgery of striving for greater and greater capital, “The true business of people should be to go back to school and think about whatever it was they were thinking about before somebody came along and told them they had to earn a living” (Barlow, pg 30).

Educational media ecology therefore can be summed up in one of my key touchstones as it relates to my own practice – meeting students where they’re at.

“Mumford’s hope and vision for a techno-organic future is one in which the machine does not disappear but is brought back under human control and into organic harmony and ecological balance” (Strate and Lum, pg. 75).

For me – and for my classroom – the machine is the mobile phone. Much of my thinking about my practice and much of my work in the MET program has been centred on how to reconcile the mobile phone and the classroom environment. I’m not of the mind that devices should be banned, but rather, as stated above, “brought back under human control”.

______________________________________________________________________

Barlow, E. (1970, March 30). The New York Magazine Environmental Teach In. New York Magazine, 3(13), 24-30.

Bush, G. (2006, December). Learning about learning: from theories to trends. Canadian Business and Current Affairs Database, 14.

Komlos, D. (2020, April 08). Don’t Fight Forces During The Pandemic, Use Them. Retrieved September 12, 2020, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/benjaminkomlos/2020/04/06/ dont-fight-forces-during-the-pandemic-use-them/

Lum, C. M. K. (2000) Introduction: The intellectual roots of media ecology. 8:1, 1-7, DOI: 10.1080/15456870009367375

Strate, L. & Lum, C.M.K. (2000) Lewis Mumford and the ecology of technics, Atlantic Journal of Communication. 8:1, 56-78, DOI: 10.1080/15456870009367379

What is Media Ecology? (2020). Retrieved September 22, 2020, from https://media-ecology.wildapricot.org/What-Is-Media-Ecology