This was a week of surprises in many ways. I pulled Box 9 from the Western Front archives (ARC- 1609) because I thought I was vaguely interested in finding out what war records the library has, only to discover that Western Front is a thriving artist center (est. 1973) located just off of Kingsway. Fitting, given that this week’s theme is “Artists’ materials” – more fitting than war records, anyways. The second surprise was that I was able to finish, and potentially even understood (debatable, but I tried) Derrida’s “Archive Fever”.

The box I was examining was a bit eclectic, and each folder was labelled with the name of either an artist or an event that had been held by the center. I chose to focus on folder 9-1 (Tasse Geldart), arbitrarily choosing based on the primacy of the folder and the interesting name of the artist.

Tasse Geldart was difficult to pin down. A cursory google search turned up a twitter account in her name with 8 tweets from 2013, and a site for a Tasse Geldart in Ontario who is a visual artist that now specializes in pet paintings. I was unable to tell if any of these identities are connected to the same person, but it is a pretty unique name, so there’s a chance they could be. I think that safest thing to say is that my efforts were inconclusive.

The information that I did have available from the Western Front file concentrated on an exhibit by Geldart from 1996, titled Over/hearing and Consumption which consisted of 2 interactive pieces: in Over/hearing, visitors overhead an argument taking place in another room, and in Consumption a fake telephone placed outside of the gallery rang every 10 minutes as an enticement for passerby’s to pick up and listen to a recording. While quite a bit of the file was random ephemera, such as a scrap of floral paper and a handbill for the exhibit that had a police report number on the back of it, the majority of the materials in the folder consisted of administrative paperwork pertaining to the exhibit. While I’m still processing Derrida and am still having a hard time articulating my thoughts on Archive Fever, the yearning I felt to actually experience the exhibit, rather than merely pour through a limited and random assembly of peripheral paperwork, made the materials of the fonds feel underwhelming in a way that made me think I maybe understand the complex sentiments of the term mal d’archive.

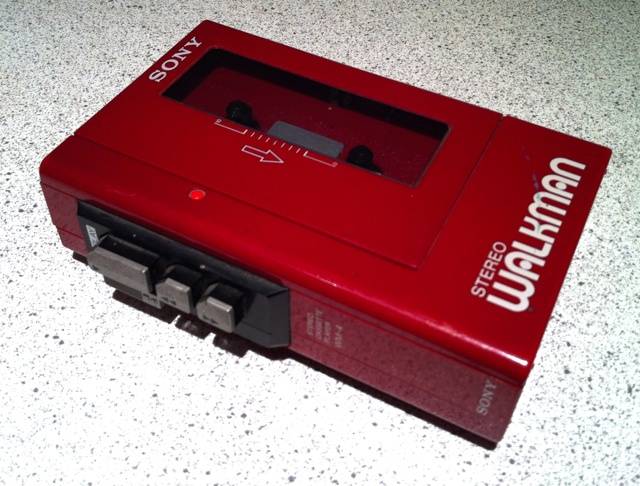

Until I got to a receipt for 5 walkmans, of all things. From the paperwork (and several apology letters) it seems that the walkmans, which were part of the exhibit, had been stolen and subsequently replaced. There was also a note that the fake telephone had been moved indoors a few days into the exhibit, as people were abusing it on the street – whether this was related to the theft of the walkmans or not, I couldn’t determine. The strangeness of looking through the shadows of shadows of shadows – there was this art piece that had walkmans which were stolen, and then replaced, and here I was 20 years later holding those receipts for the replacements – was surreal. What I wanted was to hold the original walkmans, the replacement walkmans, and/or the exhibit itself, just the way I was holding the receipt. Yet, I also knew that holding those things was impossible: the walkmans easily didn’t exist anymore, like many of their technologically obsolete brethren, or if they still did miraculously live on, they may not convey in any way that they were special in being the objects that facilitated the exhibit. Perhaps what I actually wanted was the tapes the walkmans had held, assuming I’m even thinking of the right walkman – after all, in 1996 Geldart could have been using a discman with CDs, as they were still referred to as walkmans sometimes.

A participatory art piece is unique because it necessitates interaction, so in this case I was a couple decades too late to having this experience that was necessarily time-bound in a way the the receipt was not. Interactive art can’t really be stored and archived physically the way a piece of paper can be. One of the first papers in Tasse Geldart’s file was what seemed to be an artist’s statement, and the last sentence of it read “…consuming keeps us alive at the risk of killing us”. While my feelings during my examination of Tasse Geldart’s file and my limited understand of Derrida have left me confused beyond articulation, I think my condition can maybe be characterized as archive fever – an incurable disease, brought on by the consumption of an archive.

Derrida, Jacques and Prenowitz, Eric. “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression.” Diacritics. Vol. 25, No. 2 (Summer, 1995): 9-63.

Photos by front.bc.ca and theregister.co.uk

Hello Jessica,

It is probably too late but I’m almost completely certain that the Tasse Geldart you are talking about is the same one that you found the ‘pet portrait’ website for. Tasse had received a Canada Council Grant. As a result of the work she produced because of the grant she had an exhibition in BC. She was for a number of years one of a four person collective “Artists for the City” working in Scarborough (now part of Toronto).

If it’s not too late, then I hope this info helps.

Thanks, Clarissa. This blog was part of an assignment for a class, so strictly speaking, the info is a bit late, but for my own personal information I appreciate you reaching out. Part of the mystery of the archives I found was how disconnected the can seem from the outside world, so it’s very heartening that someone was able to make the connection. I’m also very flattered that you read my blog post, as it was one of those things that I was really mostly doing for class, even though I did find it fascinating work.

Again, thank you!