It took a lot of control on my part to resist the temptation of making this blog post just a list of all the ways Facebook has changed from the version that Joanne Garde-Hansen analyzes in her 2009 article “MyMemories? Personal Digital Archival Fever and Facebook”. I’m not going to do that because it would maybe be a little bit tedious and boring to anyone who isn’t me. However, I thought the article was a great read, and helped me get into the mindset of examining social media tools from an academic perspective, rather than the blasé and somewhat brainless approach that I use in my daily life.

The idea of social media as a functioning archive is a bit weird to contemplate, given that it’s so embedded in everyday life. I’m one of those horrid people who wakes up by scrolling through my feed first thing in the morning. I thought that Garde-Hansen’s idea of Facebook as a form of database archive was an unique way of thinking about it: “One would like to say that Facebook’s emphasis upon memory, both personal and collective, allows for, an escape from history and, therefore, linearity, order and narrative” (141). I’m not sure I agree with Garde-Hansen, but that may be a function of the fact that the Facebook I use daily (multiple times a day, if I’m being honest) is pretty different from Facebook 2009. I don’t think that Facebook is an escape from history. The mere fact that my Wall (which hardly anyone refers to it as anymore; I think it’s most commonly known as your page or profile nowadays) is set to be scrolled through in descending linear order, and can be navigated as my Timeline implies that there is an inherent temporal structure in place over the information.

While I think that it is possible to view my page out of order, the primary and most prevalent impulse is to try and view something like social media as a narrative – especially since we’ve now begun to reach a time where there’s enough of our “personal histories” available in the database to constitute an archive of ourselves. Nothing on Facebook is quite as frightening as the new-ish “On this Day” feature, which can (and does) notify you of your activities throughout the years of your account’s life. Facebook remembers and reminds you of details from your past, whether you want it to or not: “users will not be sheltered from the fact, nor forget, that this digital space may well forever store memories they would prefer to forget. (148-9)

I especially liked Garde-Hansen’s idea that “the interface that Facebook has created to its database is supposed to be about telling stories, beginnings and endings, developments and organisation” (142), especially since I just read somewhere (can’t remember where, and frantically searching through 3 prior weeks of my readings turned up futile so I gave up after half an hour) about how social media is just the middle bit of the narrative on constant loop, always offering a doorway into the middle of a treadmill that allows neither forward or backward movement. The contesting problem of the innate desire for a narrative frame set against the inherent lack of one in daily life is a concept that some of the more renown philosophers spend the better part of their lives thinking about; its a bit absurd to think that something as basic as Facebook can serve as a manifestation of this struggle. Absurdity doesn’t make it untrue, though.

Garde-Hansen ends her article by proposing that “communicating our life stories online leaves us with more questions than answers” (148), which I completely agree with. My own burning Facebook query is something that Garde-Hansen sort of gestures to, but put bluntly is this: considering the idea of cultivating your Facebook presence by deleting posts that you don’t like or adding “artificial” events or details, or refusing to undertake these activities and instead letting your Facebook profile develop “naturally”, what do these different impulses mean for Facebook as an archive? Many people will dramatically change the content of their profile if they’re job hunting, or will cull pictures of their younger, more awkward selves (how glad I am that my prepubescent self did not yet know of the digital archive!) Can we still consider Facebook, and other social medias such as Twitter, Instagram, etc as true archives if we are the highly biased curators who wield a rigorous ruler of what we want or do not want preserved? Food for thought.

Garde-Hansen, Joanne. “MyMemories? Personal Digital Archival Fever and Facebook.” Save As…Digital Memories. Ed. Joanne Garde-Hansen, Andrew Hoskins, and Anna Reading. London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2009. 135-50.

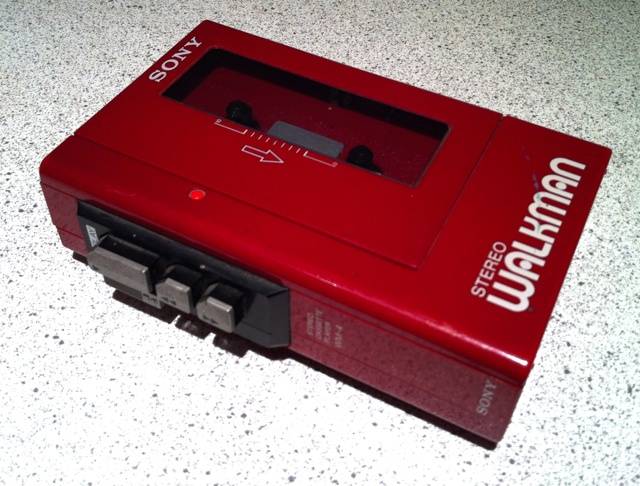

I know I said that I wasn’t going to analyze how Facebook has changed, but I can’t help it. Garde-Hansen’s article itself as an archive of what Facebook used to be is just too amazing. Here’s what I thought was most amazing: “Sometimes users create mini-archives of photos that are added to and shared by multiple users on a specific theme, for example, an archive of bad hair cuts from the 1980s, and these stand as testament to a collective memory of a cultural moment” (142). I don’t know anyone who has a personal photo album titled Bad 80s Haircuts as the article suggests, but this is a prime example of something that still exists on Facebook – today it would probably be hosted on some clickbait-y site. Some things never change, even if technology advancement surpasses the speed of sound, or even light – things like the hilarity of horrible 80s hairstyles.

With no idea what to expect, but assuming that I would wind up with some dry paperwork of census reports or something of the like, I was very surprised upon requesting Box 20 of the Vancouver Status of Women fonds (call code RBSC-ARC-1582 if you would like to take the files out from Rare Books and Special Collections yourself!) to discover that they were absolutely stuffed with newspaper articles.

With no idea what to expect, but assuming that I would wind up with some dry paperwork of census reports or something of the like, I was very surprised upon requesting Box 20 of the Vancouver Status of Women fonds (call code RBSC-ARC-1582 if you would like to take the files out from Rare Books and Special Collections yourself!) to discover that they were absolutely stuffed with newspaper articles.