On Wednesday, July 5th, I showed up in all my best clothes with coffee and maple syrup in hand to the office of what is Belgrade’s infamous Institute for Urban Planning. I had arranged beforehand to volunteer with UrBel (their colloquial name) so that I could get an insider’s perspective on Belgrade’s fascinating planning history and see how the planning process differed from Vancouver’s.

I had no idea what to expect – knowing Serbs, I thought maybe it would be a bit disorganized or that I would be doing some menial intern labour like sorting paperwork. But what I found was an incredibly well-established, extensive, and interdisciplinary network of very passionate urbanists who were very excited to put me on the newest and most important projects in the city!

Since 1948, UrBel has been the primary decision-making locus for Belgrade’s spatial development, but the tradition of urban planning in Belgrade goes back much farther than that. My first task was to learn the history of Belgrade so as to better understand it’s current planning context. So here’s a brief run-down of what I learned:

A War-torn History

Belgrade’s history begins at the site of today’s Kalemegdan fortress, a hill at the delta of the Danube and Sava rivers which was settled around 7000 BCE by the ancient Vinca culture. Because of its unique position at the confluence of the Eastern and Western worlds, Belgrade changed hands between the Celts, Romans, Turks, Hungarians, Austrians, and finally the Serbs, and suffered almost endless warfare. There were an estimated 115 battles over Belgrade and the city was burned to the ground and rebuilt 44 times.

The City within the Wall

The Kalemegdan fortress served as a military stronghold since the time of the Roman rule, and the city was basically contained within a very large, strong wall made of earth and fortified with white stone. This is why it is called Belgrade, which means “white city” in Latin. The Romans needed a place for their soldiers and families to live, so they started to expand Belgrade on the outskirts of the wall along long, grid-like streets that still exist today. This was the beginning of urban planning in Belgrade.

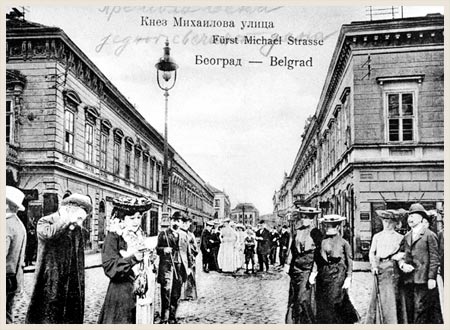

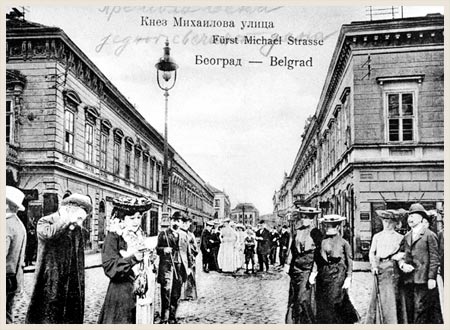

Expanding the City

The continued expansion of Belgrade beyond the Kalemegdan fortress was the inevitable result of various empires needing more space to house their growing populations. Many features of the Austro-Hungarian rule, for example, are still visible in the design of the city center, including the grandiose merchant buildings of Knez Mihajlova Ulica (Prince Mihajlo’s Street), the logically planned city grid, and the large open squares with circular gardens. Other parts of Belgrade still retain their Turkish influence, with winding street-scapes and shorter buildings clad in stone. But many parts of the city are uniquely Serbian, such as the lively Bohemian quarter, Skadarlija, where all the poets and artists sought refuge in kafanas (a mix between a cafe, a pub, and a traditional restaurant) during times of political strife and suffering. It was in these places that a true Serbian identity was able to survive until the modern day. In 1867, Belgrade’s first urban plan for the re-modelling of Kalemegdan as a park rather than a military fortress was put in place by our first urban planner, Emilijan Josimovic, to showcase Belgrade’s pride in itself as a city.

Risen from the Ashes

Like many European cities, Belgrade was ravaged during the World Wars, but it provided an opportunity to grow the city almost from scratch in a way that reflected the best of all of Serbia’s cultures and a true Beogradjanski identity. In 1948, a plan for the reconstruction of Belgrade was laid. As the new capital of Jugoslavia, Belgrade experienced several decades of economic, cultural, and population growth, and an ambitious plan to expand the city included entirely draining and in-filling the swampy forests across the Sava river to make space for the development of Novi Beograd (New Belgrade).

Communism and Modernization

Novi Beograd embodied a modernist dream – rationally planned in huge grid-like blocks, each with its own unique “theme” or identity. Beogradjani at this time were very fond of Josip Broz Tito, Jugoslavia’s communist leader who brought peace and prosperity to the Balkans, and many icons in the city are dedicated to him, not to mention the inspiration for Novi Beograd’s design. It was very much an experiment in planning, meant to at once reflect socialist/communist values, and also showcase Belgrade as a modern, world-class city. Each Blok has uniquely shaped buildings and lots of communal space, and from above appears like a patterned quilt.

The Breakup of Jugoslavia and the NATO Bombings

The 1980’s and 90’s were a dark time in Serbia’s and Belgrade’s histories. The Jugoslav War ravaged the country yet again, and countless protests were held against the Milosevic regime in Belgrade. Economic chaos and sanctioning stopped Belgrade’s growth in it’s tracks and many urban projects are left unfinished to this day. The 1999 NATO bombings destroyed many buildings in Belgrade and the need to rebuild and repair drained the city of a lot of its resources.

Getting By

The 80’s and 90’s saw a rise in illegal activity and black markets in Belgrade. Many government-owned buildings that were not returned to their pre-Communism owners were illegally overtaken by young people looking to start businesses. An interesting example is the old brewery building in Skadarlija which is now inhabited by many quirky nightlife spots, including bars, concert venues, nightclubs, and kafane. Another interesting example of illegal activity are the splavovi (boat houses) lining the Sava and Danube, which are basically floating barges converted into restaurants and nightclubs. Splavovi were totally illegal once, but soon they were seen as a major source of revenue and social capital, and are now written into Belgrade’s urban plan. Finally, Belgrade is quite famous for its graffiti – a visual hint at the deep subculture of struggle and disillusionment with the end of the 20th century and the bleak beginnings of the 21st.

Belgrade Today

Despite thousands of years of constant warfare and political struggle, Belgrade has always been a resilient city. Today, the focus of urban planning is two-fold: first, to make the city more livable; and second, the preservation of historic, cultural, and natural elements. UrBel is taking the lead on a variety of projects aimed at increasing Belgrade’s livability, including plans for better public transportation infrastructure, waste management, and the refurbishing of parks and public spaces. Many urban design projects emphasize public art and placemaking with attention to open areas, playgrounds, and multifunctional spaces for social and cultural activities. In terms of preservation and refurbishing, the goal is to integrate historical buildings, monuments, facades, etc. with the 21st century ebb and flow of Belgrade. So far, this has lead to an incredibly interesting mash-up of old and new, history and present, past and future. Belgrade today is a city brimming with life, but growing out of historical and cultural roots so deep that they have survived through millennia.