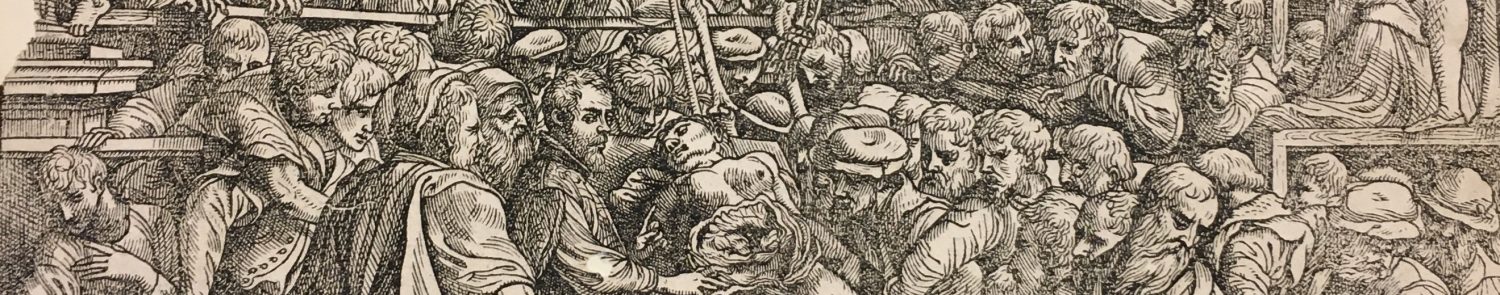

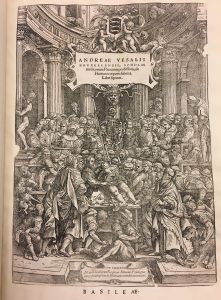

This woodcut ranks among the finest achievements of 16th century engraving (Saunders and O’Malley 42). The lines are clear, the cross hatchings remarkable in their ability to demonstrate depth and perspective. On the whole, the title page of the Fabrica is as strikingly beautiful as it is chaotic.

Title page, De Humani Corporis Fabrica, 1543 (UBC Rare Books and Special Collections)

In the scene, young Vesalius conducts a public anatomy, surrounded not only by his students and fellow physicians but by members of nobility and the church (Saunders and O’Malley 42). Vesalius stands with calm authority at the centre, dissecting a human body. Interestingly enough, it is a female body that he dissects. This is noteworthy because the Fabrica is largely composed of male bodies, save for an erroneous depiction of the female reproductive system.

For the most part, Vesalius held masculinist assumptions about the human body. In other words, he assumed that a woman’s body would mimic that of a man’s. In Vesalius’ work, as a result, there was no recognition of fallopian tubes, ovaries were assumed to have a braided body like those of the male epididymis, and women were assumed to produce ‘seed’ at orgasm (Hobby 2017). These errors indicate both a cultural assumption of the male body being the norm, as well as the practical difficulty of acquiring female corpses for dissection (Hobby 2017). Such a shortage would surely have an impact on Vesalius’ work.

In any case, on the title page, Vesalius dissects a female corpse. Beneath him, quarrelling under the table are the relegated menials who formerly did dissections (Saunders and O’Malley 42). In the foreground, three robed men represent the golden age, now on the same level as those of the new age (Saunders and O’Malley 42). This, supposedly because Vesalius spoke of his hope for anatomy to one day be “cultivated in all of our academics as it was of old in Alexandria” (Saunders and O’Malley 42).

A skeleton presides over the event, a clear marker of death and that from which Vesalius derives his learning. Above that appears the lion head of the Venetian state and the ox of the Paduan school. Here we have the title, and above that still a shield carrying three weasels–an apparent play on the vernacular of Vesalius’ name: Wessels (Saunders and O’Malley 42).

Finally, on the upper left, right above the figure leaning out of the balcony window are the interlaced initials I and O, representing the monogram of publisher Johannes Oporinus (Saunders and O’Malley 42).