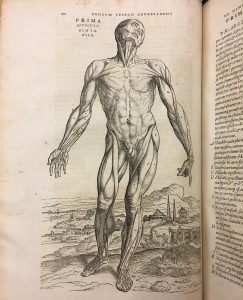

A ‘Muscle Man.’ De Humani Corporis Fabrica, 1543 (UBC Rare Books and Special Collections)

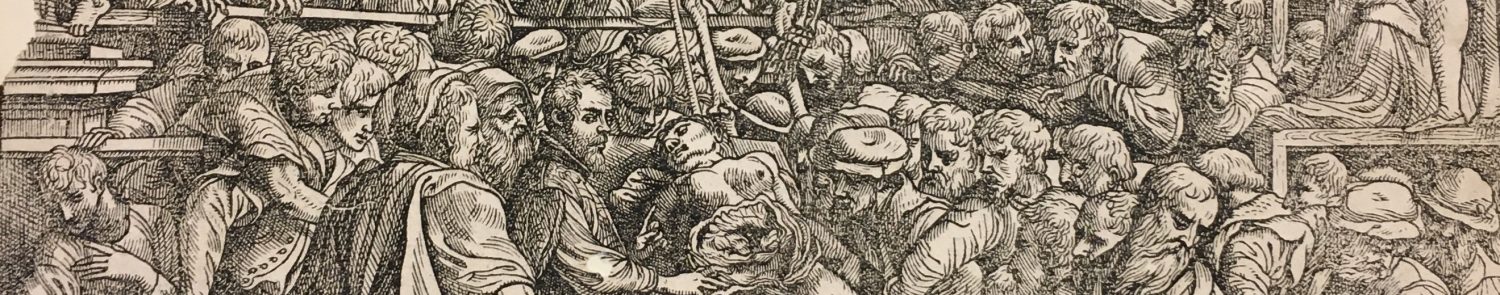

The publication of the De Humani Corporis Fabrica in 1543 was not just a great contribution to science, but a revolutionary work of creative art, weaving medical technicality with imagery and the printed word. An accomplishment of at least 4 years in the making, the Fabrica is a structural examination of the human body, complete with woodcut engravings of Vesalius’ dissections.

Notable features of the work include 3 full skeletons in dramatic pose, and 14 frontal and dorsal views of the human body in successive states of dissection (often referred to as the ‘muscle men’).

The work is divided into seven books as follows:

- Bones and cartilages

- Ligaments and muscles

- Blood vessels

- Nerves

- Abdominal organs

- Thoracic organs

- Brain and special senses

Anatomy Meets Print

Gutenberg invented printing around 1430-1440. The impact of the printing press on scientific progress is hard to measure, but in general, scholars seem to agree that it helped accelerate scientific communication. In Emergence of Print Culture in the West, Eisenstein (1980) argues that print revolutionized scientific communication with precise pictorial representations. This is especially evident in anatomy (a field dependent on reproducible illustrations), now invigorated with the ability to create precise and timely duplications of images.

The publication of the Fabrica marked a new era of anatomy and print. But to really understand the extent of Vesalius’ achievement we must consider the history of print and anatomical illustrations on a continuum, beginning some fifty years prior to the publication of the Fabrica. The earliest printed medical book featuring the natural representation of an organ is the Fasciculus Medicinae, 1491 (Saunders and O’Malley 23). The featured illustrations were skillfully drawn, but only vaguely anatomical, laden with errors that suggested the draughtsman had constructed the bodily images from memory (Saunders and O’Malley 23).

The first book to illustrate anatomy in a modern sense was Commentary, 1521, by Jacopo Berengario da Capri. The woodcuts were oftentimes crude in their depictions, but the book was the first to employ dramatic postures in representations of the body, something that Vesalius is likewise renowned for (Saunders and O’Malley 23). Just before the time of Vesalius’ publication, notable anatomist Giovanni Battista Canano (1515-1578) published illustrations of his own dissections in a work titled Musculorum Humani Corporis Picturata Dissectio. The drawings consisted of the muscles and bones of the arm, forearm and hand, and demonstrated considerable advance in the artistry of anatomical illustration (Saunders and O’Malley 24).

Making the Fabrica

It was Vesalius’ Fabrica, however, that took anatomical print to the next level. The sheer grandeur of covering the entire human body in detail, artfully and with an evidence-based approach was previously unheard of. The Fabrica depicted human anatomy more completely and accurately than any previous work (Clark 302).

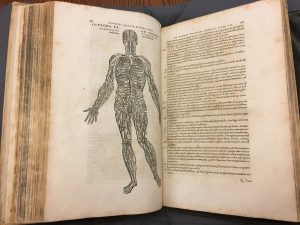

Vesalius’ daunting project required collaboration on multiple levels: between artists, printer Johannes Oporinus, as well as Vesalius’ own research. The entire project seemed to have been of a complicated, feedback-dependent variety. Vesalius immediately sent completed books to the printer. While these texts were being composed in Basel, the accompanying drawings were being cut into wood in Venice. Each of these illustrations was accompanied by an ‘Index of Characters,’ or legend, and as the illustrations were cut, Vesalius made adjustments in accordance with his ongoing discoveries (Saunders and O’Malley 20). Evidence suggests that many illustrations, like those of the vascular tree depicted below, were modified from Vesalius’ own sketches and altered over-time as more discoveries were uncovered via dissection (Saunders and O’Malley 20).

Vascular system, book 3, pages 268-269. De Humani Corporis Fabrica, 1543 (UBC Rare Books and Special Collections)