“Human brains are exquisitely evolved to adapt to the environment in which they’re placed. It follows that if the environment is changing in an unprecedented way, then the changes too will be unprecedented…So the fear I have is not with the technology per se, but the way it’s used by the native mind.”

–Susan Greenfield. In The New York Times (2012).

After watching Danah Boyd’s YouTube video, It’s Complicated, it became clear that her experience using the Internet was very transformative, and maybe this experience was just as transformative for young people. Her questions complement my last post and beg the question: How does technology change everyday life? Much of what Boyd discusses speaks to anxiety and concerns from parents and seeks to address individuals’ motivations for staying connected.

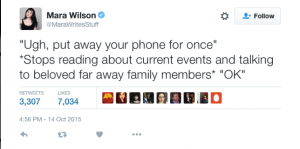

She raises a very important idea: “What young people are doing and what we blame young people for doing is not necessarily the best way to look at it and we need to actually look at our own practices.” She points out that we often blame young people for things that adults also do. Boyd recalls experiences watching parents staring at their phones through the entirety of their children’s sports games.

Even as a young adult I am told that I need to get off my phone and smell the roses. My offline self, however, always bleeds into my online self, and it can be hard to distinguish between the two. Obviously I know the difference of physically being on and offline, but lines get blurred when we talk about privacy, or the work place. E-mailing your boss on a Sunday night, for example, may be considered inappropriate. On the other hand, she may need specific information before Monday.

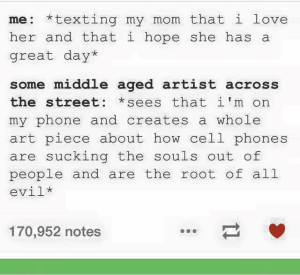

I am not addicted to my phone. Some of my motivations may be as simple as texting my mother to tell her that I love her.

There are various, non-life threatening reasons young people are motivated to stay online. Staying connected is simply one extra avenue through which we can, and should, stay connected to each other.

It is true that young people consume (and produce) an extraordinary amount of media. A study in 2010 from the Kaiser Foundation found that teens were spending seven hours and thirty-eight minutes on their devices every day. Although this sounds alarming, it is important to keep in mind that many young adults multitask and consume multiple media channels at once. This could include texting, watching a YouTube video, updating Facebook, and at the same time polishing off an essay. Connectivity can be achieved sporadically throughout the day—not just sitting in one place. Millennials have been brought up in a world of ubiquitous technology and should not be expected to avoid using it. Since there are such high concerns about young people being addicted to their technology, perhaps instead of telling Millennials to unplug, it might be more useful to come up with constructive ways to educate young people on the ways in which technology can be useful in the Information Age.

We don’t need strategies on how to break our addictions to our cellphones. We are simply adapting to the environment in which we have been placed, including using educational information technology to aid us. One place that we can begin to break down these barriers and talk about the benefits of technology is the library. Other spaces such as school and the home should also prioritize discussions on innovative, responsible, and safe technology use.

References

Boyd D. “It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens.” New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014.

Greenfild, Susan. Are we Becoming Cyborgs? The NewYork Times, 2012.

Kaiser, Henry J., Family Foundation. “Generation M2: Media in the Lives of 8-18 Year-Olds.” 2010. Web.

Images

https://twitter.com/marawritesstuff/status/654445828925472768