This blog post is a response to prompt #1, which ultimately boils down to:

Why does King give us this analysis that depends on pairing up oppositions into a tidy row of dichotomies? What is he trying to show us?

It might seem prima facie contradictory, or at least counterintuitive, for King to warn us about taking binaries for granted only to then provide two creation stories framed as being diametrically opposed. My initial thoughts regarding this inconsistency are that King is illustrating the arbitrariness of dichotomous organization. Simply by “us[ing] different strategies in the telling of these stories,” he is able to “colour the stories and suggest values that may be neither inherited nor warranted” (King 22). Thus, this complicates the notion that binaries are inherent or naturally formed; they can be and often are influenced by factors outside of the intrinsic characteristics of the objects/notions being compared, such as how they are presented to us.

Furthermore, since we are positing both of these stories as being opposites and therefore in contention with each other – in other words, if we agree that “if we believe one story to be sacred, we must see the other as secular” (King 25) – then we are forced to a moment of decisiveness. We must decide which one to deem sacred and which one is secular, and the way that we make this decision will be affected by the way that we construct this binary in the first place. Thus, by King telling the Christian creation story in a way that “creates a sense of veracity” (King 23), we are influenced to the believe this story over the other creation story for gratuitous and extrinsic reasons. I think the point we are meant to grasp is that King could have just as easily told the story of Charm with this serious intensity and tone, and we may have chosen to believe that creation story instead. This goes to show that our choice has little to do with the innate believability (or unbelievability) of the story’s content; rather, our decisions are informed (perhaps subconsciously) by how these ideas are presented. If this is the case, then we are being encouraged, in a roundabout way, to rethink our conception of these binaries by questioning the real reasons for characterizing them as opposites.

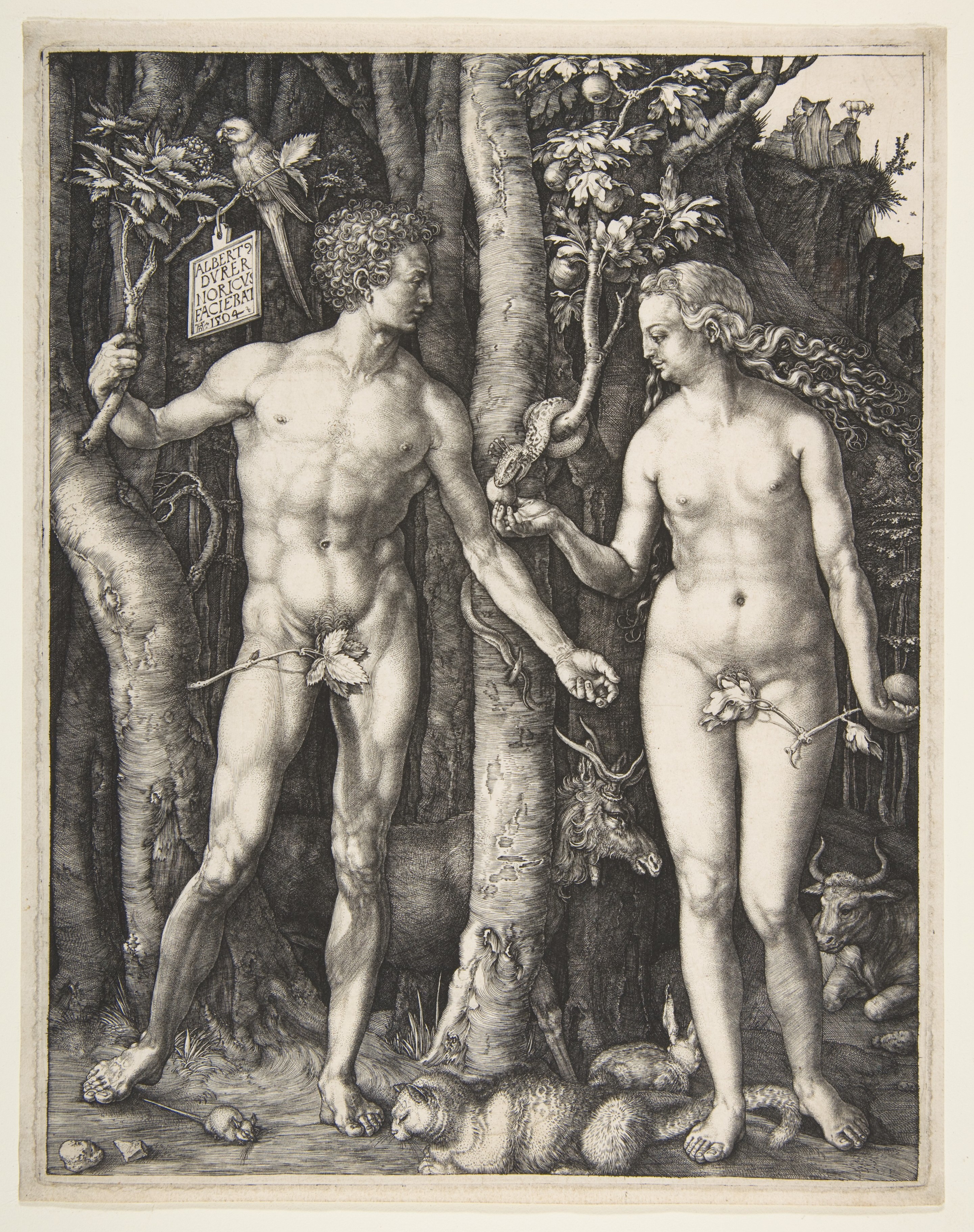

When I tried to find images of the Indigenous creation myth, I tellingly could not find anything; however, there are hundreds of renditions of Adam and Eve. This one is a print by Albrecht Dürer and dates to 1504.

As someone with some background in philosophy, I wanted to bring up a philosopher named William James who I think may be relevant to this conversation. In his famous paper, “The Will to Believe,” James talks about what he calls ‘live hypotheses’ and ‘live options.’ His paper is meant to be in dialogue with the Philosophy of Religion, as he uses the view expressed in this paper (called pragmatism; I will link a quick video explaining it here, but the rest of his theory does not really bear on this post) to defend religious belief, but I think parts of his thinking can be applied to our discussion here. He defines a “live hypothesis” as “one which appeals as a real possibility to him to whom it is proposed,” while a “living option is one in which both hypotheses are live ones” (James n.p). Thus, perhaps the choice that King is asking us to make is not really a choice to us at all; one of the hypothesis is dead, since “we live in a predominantly scientific, capitalistic, Judeo-Christian world governed by physical laws, economic imperatives, and spiritual precepts” (King 12). We are therefore more prepared to believe in a hierarchical creation story than a collaborative and egalitarian one; the Indigenous story is then a dead option, meaning that there is no real choice to make. However, more pertinently, James also provides a way to accommodate both creation stories. As he points out, the “deadness and liveness in an hypothesis [sic] are not intrinsic properties, but relations to the individual thinker” (James n.p). Thus, while one hypothesis may seem dead to us, that does not mean that is dead to all. Perhaps this is a way of accommodating both stories as true, and a way of thinking that may move us towards a less binary worldview.

If I had to come up with another reason, though, for King’s strange inconsistency, I might say that King is pointing out how easy it is to fall into these binaries, even after we have been told to be cautious of them. It is very difficult for us humans to ‘de-binarize’ our thinking; we need look no further than one of the most prevalent dichotomies – male/female – to see just how troubling these binaries can be and how difficult it has been for those who identify as non-binary to try to dismantle them. Thus, perhaps King is also demonstrating that no matter how aware we are, we are still prone to this kind of thinking: it is a process of unlearning that we must embark on consciously and over a prolonged period of time. I would add as a final comment that not every culture seems to tend towards binary thinking, but the one in which we find ourselves most certainly does, and so it is our duty to be critical of how we organize the world.

I am looking forward to hearing what you all think, both about the question and my response to it. I think there are a lot of different ways to interpret King’s dichotomy, so I am curious to see yours!

Works Cited

Bergner, Daniel. “The Struggles of Rejecting the Gender Binary.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 04 June 2019. Web.

James, William. “THE WILL TO BELIEVE.” The Project Gutenberg E-text of The Will to Believe, by William James. Project Gutenberg, 8 May 2009. Web.

King, Thomas. “”You’ll Never Believe What Happened” Is Always a Great Way to Start.” The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative. House of Anansi, 2010. 1-29. Print.

“PHILOSOPHY – Epistemology: The Will to Believe [HD].” YouTube, uploaded by Wireless Philosophy, 24 May 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uzmLXIuAspQ

Dürer, Albrecht. Adam and Eve. 1505. Engraving. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Great post! Thanks for your linking to James and his pertinent examination of religious faith, truth, and evidence. Epistemology is complex but it seems this course is building towards this examination of knowledge and belief systems. I think we must be careful, however – and your posts demonstrate you are well aware of this – that we must frame our considerations of belief and story within the history of Western settler colonialism and the theft and appropriation of Indigenous narrative and culture. So does the genocide of Indigenous knowledges – linguistic, cultural, environmental, spiritual – complicate the question of what it means to *know*?

I think we ultimately arrive at the same or at least a similar conclusion in noting the dangers of falling into dichotomous or hierarchical forms of knowledge. So do some of our other classmates, to varying degrees and in illuminatingly different ways: Cayla wonders as to how Biblical narrative and Christian forms of knowledge would have been incorporated into Indigenous culture in different or greater ways had there not been a genocide of Indigenous knowledges by the Canadian settler colonialist state. Zac delves into the problematics of binaries, and notes, as you do, the dangers of dichotomizing gender identity and expression; this conversation of what you call the difficulty to “de-binarize” knowledges and thought processes is interesting.

A pragmatic interpretation of this course’s considerations on storytelling and knowledge is interesting, and returns us to J. Edward Chamberlin and what he notes in his introduction to “If This Is Your Land, Where are You Stories?” as the storytelling traditions of the world telling “The different truths of religion and science, of history and the arts” (2). How can there be different “truths” if we are to employ the word’s dictionary definition? Perhaps we actually can, because the second definition from the Oxford Languages notes it as “a fact or belief that is *accepted as true*.” And this is what James is getting at, the suspension of of evidentialist considerations of truth in favour of subjective belief.

You pull a quote from James that I find highly pertinent, that of the deadness and liveness of a hypothesis being “relations to the individual thinker” measured “by his willigness to act” (James n.p.). Perhaps we slightly can alter James’ formulation of the contingency of a hypothesis’ relative “aliveness” as dependent upon relations to the community rather than simply just the individual thinker. This is particularly helpful, perhaps, in examining Indigenous storytelling traditions as community-based, egalitarian and thus non-hirearchical, dependent not upon the beliefs of one person but rather those of a greater collective; and of course, the collective is what the Canadian state was (and continues to be) attempting to erase through its cultural genocide of its Indigenous peoples – through, for example, the residential school system in the destruction of Indigenous identity and communality.

One last thought – when you write that “the Indigenous story is then a dead option,” do you mean to say that the choice between Indigenous and Judeo-Christian forms of first story is a dead option? Or is it something else?

Hi Leo, thank you so much for your thoughtful reply!

I think you’ve raised some really interesting points here. Firstly, regarding how the genocide of not just Indigenous people but Indigenous knowledges complicates our epistemological structures is really relevant. Philosophy tends to be deeply rooted in Western tradition (cf. the famous remark by Whitehead that all of philosophy is a footnote to Plato), and tends to ignore Eastern or non-Western philosophical content – or if it does, it tends to be appropriated. Thus, I think this could suggest that epistemology itself is deeply rooted in Western conceptions of knowing, and so this is why it has been so easy for settlers to brush off Indigenous knowledge – it does not fit this framework. I am reminded here of novels like Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer, who’s Indigenous ways of knowing nature and her resulting interest in botany were discounted at the beginning of her career in favour of more formalistic, ‘scientific’ ways of knowing. So, perhaps what I am trying to get to is the idea that our conception of ‘know’ in the epistemological sense is deeply tied into a colonial mindset, and thus perhaps we need to broaden our conception of what it means to know.

You say so many other interesting things, especially in regards to James, but I want to make sure I address your final question. What I meant to say is that, in a Judeo-Christian/capitalistic/colonial world, the hypothesis (to use James’ terminology) of an Indigenous creation story is a dead one because it is not relevant to how we conceive of our culture, at least broadly speaking. King himself points out: “…you’re probably wondering how in the world I expect you to believe any of this, given the fact that we live in a predominantly scientific, capitalistic….” (ETC.) (12). Thus, the ‘choice’ is not really a choice (it’s a dead choice) at all, because one of the hypotheses is a dead one for our culture. I think King is less wanting us to adopt the Indigenous creation and more wanting us to reconsider the idea that there can be only one truth, and encourages us to reflect on how these stories shape our worldview.

Thanks so much again for your reply, it is really pushing me to think outside the box!

Good morning Victoria!

I had a great time reading your post and brought up some really good points that I would never have thought of. As a human geography major and English literature minor, I often forget about philosophers and the assets that they bring to analyzing questions like the one King proposed.

With this being said, I found it really interesting about the difference between the live and dead hypothesis and the key point that you raised: one hypothesis may be dead, it may not be dead for all. I think that this point is important to be mindful of this to be respectful. Nonetheless, we still continue to fall into us vs them and unconsciously separate ourselves into binaries, that some of us actively try to break.

I was wondering, what do you think would happen if there were fewer binaries… would the world be a better place and would creation stories and first contact stories be more open to others worldviews?

Hi Lenaya,

Thanks so much for the kind words! I have personally found philosophy to be very valuable in thinking about a lot of literary issues, so I’m glad it helped you too!

In regards to your excellent question, my first intuition would be to say that yes, I do think the world would be a better place if it weren’t for so many strict binaries. The problem with binaries is that they do not simply place two things in opposition; it is not, for example, like “hot/cold,” where neither is afforded any real privilege over the other. With binaries, they are often bound up with ideas of superiority, and this is where oppression arises. Male/female, black/white, us/them – all of these are not only interested in categorizing things in opposition, but also in establishing a relationship of dominance. Thus, it seems that if we could undo these binaries, it may be helpful in undoing these ideas of dominance. This would extend to creation stories; if we were to undo the binary of true/false, where true is the superior and everything else is inferior, we may be able to see that truth is not as objective as we may want it to be, and thus be able to accommodate both different creation stories and the worldviews that come with them.

However, I also recognize that this is easier said than done. How do you undo centuries of conditioning? Furthermore, while binaries are almost always an oversimplification, they are just that: simple. To try to reorder our world might take more complexity than we may be willing to commit to. So, I am not sure how achievable this really is a goal. But, ideally, I do think less binaries would improve living conditions for a lot of people.