In 2010, the Swiss Confederation implemented the greenhouse gas emission trading systems (ETS) along with the other European Union countries.

Overview of the ETS

The ETS is basically a “cap and trade” system which provides a quota or cap on the overall level of emissions. This market allows participants to trade permit to pollute. In effect, the permits or allowances serve as a currency with the ETS carbon market. Each one gives the permit owner the right the emit one tonne of CO2. This system is effective in a sense that the cap is imposed on the total number of allowances, which allows market scarcity to drive incentives to reduce emissions to an optimal level.

The ETS involves over 10,000 individual installations with heat excess of 20 megawatts in energy-intensive sectors, such as electricity and heat generation, meal production and chemicals. In aggregate, this is approximately half of EU’s CO2 emissions and 40% of total green house gas emissions.

ETS in Switzerland

Switzerland operates as a voluntary alternative to a domestic fuel tax with 40 companies that covers 6.9% of Switzerland’s 52 Mt of annual CO2 emissions. From 2012 and onwards, the ETS has been extended to the aviation industry.

Switzerland’s carbon emissions and tax policy

Main sources of CO2 emissions: oil used in transportation and space heating (40%), combustible and renewable waste (7%), and fossil fuel (53%) as of year

Policy to curtail emissions: CO2 tax is implemented to have polluters to finance for decarbonisation efforts in space heating

Counter-factual environmental taxes: consumption of final and intermediate carbon-intensive inputs, which is also adopted in Finland and Norway

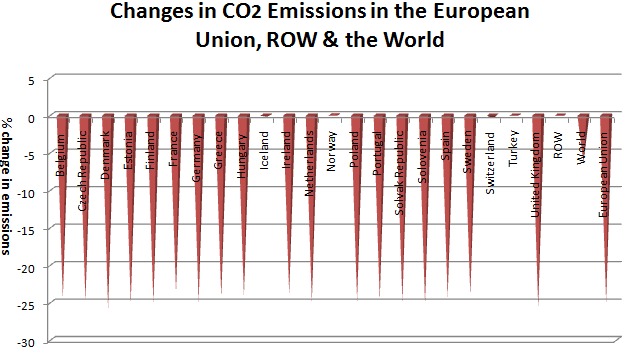

Back in 2009, the European Union and Switzerland set a target of a 20-30% reduction in emissions relative to 1990. The result shows that Switzerland is on the sensible lower bound of the pledged target reduction in CO2 emissions relative to the world.

Tax on CO2 intensive inputs

In regards to inputs, Switzerland has introduced such form of carbon tax under the Copenhagen Accord.

Factors causing major shortfalls in the Copenhagen Accord:

1) The agreement between nations is not legally binding. Rather, it is through voluntary, unilateral measures (ie: domestic tax).

2) Heterogeneous targets for emission levels across countries

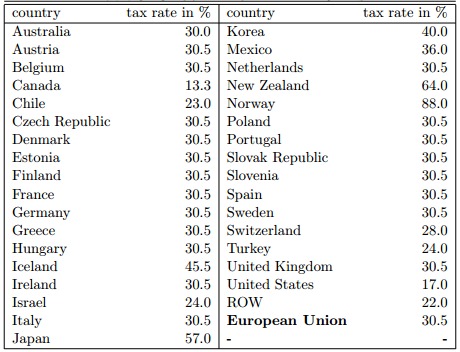

Tax rates are necessary to achieve targets on a variable basis. In fact, tax brackets are identical across the European Union member countries in which the members implemented a coordinated environmental policy.

Thus, the European Union has a uniform target of a 25% reduction in CO2 emissions and a uniform tax rate of 30.5% across all member countries. The worldwide impact is that there is a cutback in level of emissions of 6.4% reduction in cost of the European Union’s total welfare, though the welfare effect varies within individual countries.

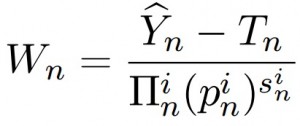

Note that Welfare Cost, Wn is denoted as the % change. It is calculated as follows:

Where Y ̂n denotes the changes of nominal GDP in response to the imposition or the change in carbon tax. In this case, we deflate the change in nominal income of consumers in n by the aggregate prices normalized by consumption share parameters.

Without coordinated efforts, the consequences of aggregate carbon emissions would not be taken into account.

- Result: Geographical reallocation of polluting industries, in which efforts in energy use reductions in some countries are partially offset by carbon leakage

Thus, it is important to have policy alignment across countries in order to reduce effort of individual countries relative to uncoordinated implementation. This is due to the fact that domestic tax policies only provides second order indirect effect on the rest of the world.

Switzerland’s case as a small open economy (S.O.E.)

Firm’s Options for abatement activities and carbon emissions:

1) Participate in Switzerland’s cap and trade program, given that firms are committed to “cleaner” environmental technologies

Advantage: exempts firms from environmental taxes, which was 36 Swiss Franx per ton of carbon back in 2011

2) Pay for the carbon tax as specified in the federal law on the reduction of carbon emissions

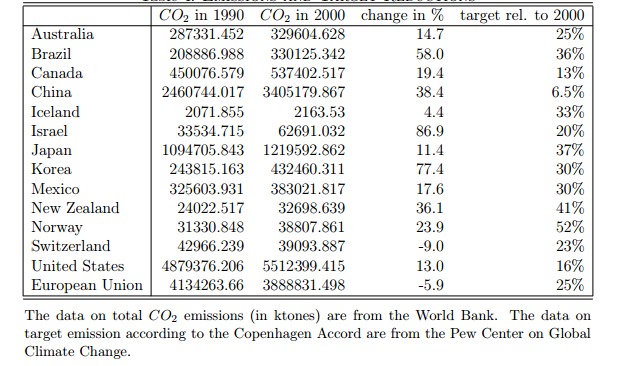

The Swiss government implements a direct carbon tax and distributes annual tradable permits throughout the year. According to the Copenhagen accord, Switzerland’s unconditional target of reduction in CO2 emissions is 23% relative to 2000.

In general, the effect of Switzerland’s domestic policies has a relatively small impact to the world since it is a small open economy.

Based on the analysis from the Economic Suisse Journal, to achieve a 23% reduction in carbon emissions, Switzerland would need to set carbon tax at 28% in 2000 which translates to 57.2 Swiss Francs per ton of tax (as in 2011).

Normalizing using the real GDP deflator for 2000 and 2011:

Taxn = 0.28 * (YnCO2 / CO2)* deflator

If the Switzerland and the EU countries comply with their target reduction in which the European Union member countries implement a carbon tax of 30.5%, Switzerland will be able to meet its target of CO2 reductions using a slightly lower tax of 53.1 Swiss Francs than implementing alone (57.2 Swiss Francs as in 2011 terms).

It is important to note that if both the European Union countries and Switzerland implemented their environmental policies, this would be beneficial for the world through lower CO2 emissions.

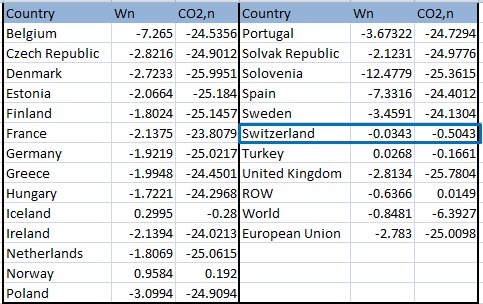

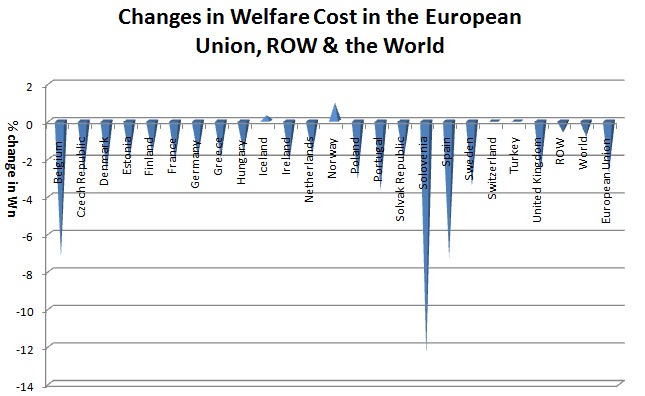

Data in Egger, and Nigai’s “Energy Reform Switzerland” suggests that the world level of carbon emissions of the OECD would fall by 8.6%. Switzerland and the European Union would have a change in welfare costs of -1.7% and -2.8%, respectively. See graphics and tabulation below.

In Switzerland`s case, it has higher welfare costs relative to the European Union. Since it is committed to more severe reductions in the Copenhagen Pledges, and as a small open economy, the competitive effects of tax policies have more adverse impacts than other large open economies.

Kyoto Protocol

At the 2012, Doha Climate Change Talk, Switzerland entered the second round of commitment in which they agreed to reduce emissions in 1 January 2013 to December 2020. By signing the Kyoto Protocol, it guaranteed that the nation would reduce emission of CO2 by an average of 8%.

The Swiss government took an innovative approach in terms of implementation of carbon incentive tax.

There are three pillars involved from the carbon incentive tax scheme:

1) The collected carbon tax revenue flows back to the industry and the households to finance energy saving projects.

2) All carbon projects are driven by local initiatives with a decentralized approach which serves as an important feature of the scheme.

3) Energy intensive sector can ask for a tax exemption if they contract a reduction of CO2 emissions. However, by having this tax benefit, these energy-intensive businesses are ineligible to obtain financial assistance from the energy fund.

If we look at the distributional effects, all of the three pillars above contribute to a greater incentive among workers, industry, and all other polluters in general to cut back on emissions.

As we can see, the first pillar focuses on taxation to polluters, which results in reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. The second pillar illustrates the money flows back into the industry proportional to the annual salaries paid to the workforce. Last but not least, this carbon tax scheme generates industry profits in two manners. First, sectors with relatively high energy efficiency pay less than the high polluting sectors. At the same time, they can also exploit the benefit of being eligible to receive a tax refund depending on their wage-bill. In essence, the government encourage businesses to innovate for higher energy efficiency. Consequently, the industry enjoys a two-fold benefit in terms of cost reduction, thereby becoming more competitive.

In terms of SMEs support, the local Swiss initiative for carbon footprint reduction was created by The Swiss Climate Foundation, which serves as an non-profit agency to encourage voluntary energy reduction, energy efficiency, and climate protection projects for the development and marketing of innovative products and technologies.

Note: The Swiss government implemented the carbon incentive tax since 2008. Swiss companies can be exempt from the tax if they participate in the country’s emissions trading system. The tax amounts to CHF 36 per metric tonne CO2.

July 2012, Nuclear Phase Out Plan

According to the IEA (International Energy Agency), Switzerland is in transition to a low-carbon economy by seeking to reduce green house has emission by a fifth by 2020, phasing out nuclear power. Even though, on the outset, it is appealing to the Swiss electricity reforms and generates high oil and gas security levels, the energy policy review in IEA foresees challenges in terms of stabilization of electricity demand.

The goal is to provide stable, long term conditions for energy market participants in 2050. IEA reports indicate that Switzerland`s significant cross-border electricity flows and its reservoir alongside plum-storage hydro-power plants could serve as good energy sources for the wider region.

Phase out plan details:

Gradual decision, in which it might take longer than the anticipated end-of-operation period from 2019-34.

As of 2012, the nuclear reactors generate 40% of the electricity in Switzerland. Given operating lifespans of 50 years, the first Swiss reactor to shut could be Beznau 1 in 2019, followed by Beznau 2 in 2021.Followed by the shutdown of Mühleberg around 2022. Last but not least, the largest units: Gösgen with 985 MWe and Leibstadt with 1165 MWe would likely to be closed in 2029 and 2034 respectively.

However, in reality, there is no notion of operational lifetime. According to the Swiss law. NPPs may operate as long as the safety criteria is met.

It is anticipated that over the longer term after 2020, the separate taxation schemes in energy and CO2 would be abolished, and would gradually be substituted by an overall energy tax, which would have a steering effect on the energy demand. New financial and institutional incentives arises as CO2 tax and tariffs has increased, and so as the eligibility of individual remuneration in technologies.

Reduction in green house gas emissions (GHG)

In terms of reduction in green house gas emissions, the target is to reduce GHG by 20% from 1990-2020. Since most carbon emission sources comes from oil use in transportation and space heating, space heating and process heat are involved in most of the carbon tax for financing decarbonisation efforts.

It is anticipated that stronger efforts will be required to reduce emissions from road transport. For end-use sectors, road transport accounts for the largest CO2 emission throughout the country, and has the most potential for further improvements in terms of abatement.

One of the important initiatives is the fleet-wide CO2 limits on new passenger cars that will take full effect in 2015.

For several years, the government has worked on improving the standard of public transit system. There were successful efforts in changes of freight traffic from road to rail. In addition, heavy vehicle fee has been levied to the emitters.

With respect to the building sector, the emissions is also high due to a large share of oil of over 50% is used in heating. Thus, Switzerland should implement more accelerated programmes and plans to adopt heat pumps and renewable energy sources for reductions in carbon emissions. In other words, the country should still work on improving incentives to increase energy saving innovations in rental dwellings; since it is a country with high share of tenants.

Problem of “Effect & voluntary” measures

This policy approach in Switzerland is deemed as ineffective, since market players are exempted from tax if they voluntarily fulfill the pre-agreed targets. However, as the need to reduce carbon dioxide emissions becomes increasingly urgent, the price-based instruments should be used more extensively.

In this manner, with higher CO2 tax rates,this helps incentivize more investments in R&D and technological innovations.

Important Policy Recommendations:

For long-term stability, the Government of Switzerland should:

1) Develop a sound and solid regulatory and policy framework in regards to the Energy Strategy 2050

2) Adopt reduction in domestic CO2 emissions in a cost effective manner by delivering a detailed strategic plan

3) Amidst the trend of ever-increasing energy demand, take action to rise incentives for electricity grids investments and increase market integration across borders

4) Closer integration with the European energy markets and extend alignment of energy policies with the rest of the European Union countries

————————————————————————————————-

The CCS Incentive – Carbon Capture & Storage

Countries involved: The European Union, North America, and Australia

Objective: To help with mass deployment by reducing emission in a cost effective manner

Challenges: Changes in policy – difficult to predict because it depends on sthe stages it takes for alternative technologies to mature

How can CCS become an effective initiative? In all the participating countries, each of the government needs to have a combination of policy that addresses various dimensions of market failure.

Project stage – technically immature in terms of integration of carbon capture, transportation, and storage in full scale.

We would need a market for CO2 capture to have enhanced oil recovery.

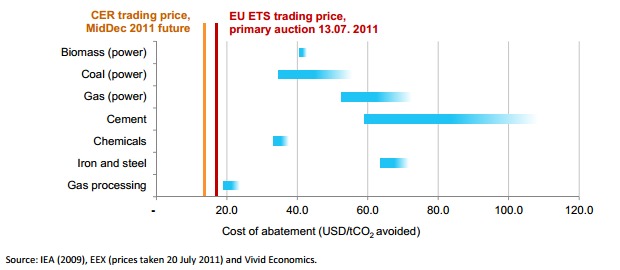

Figure 1 – Current carbon prices from EU emission trading scheme or clear development mechanism

What are the future prospects? R&D and experience from existing projects can reduce costs, while increasing carbon prices will boost revenues. Recently, there has been demonstration programs launched in the European Union, Australia and North America.

By examining the IEA BLUE Map scenario, by 2050, the CO2 emission from energy use will be 50% of their 2005 level and 19% of total emissions reduction arises from CCS.

Policy involves four aspects:

- Funding for capital deployment and operations

- Costs & risks: either public or private

- Subsidies or penalties

- Technological support: CCS specific incentives (ie: technology neutral incentives)

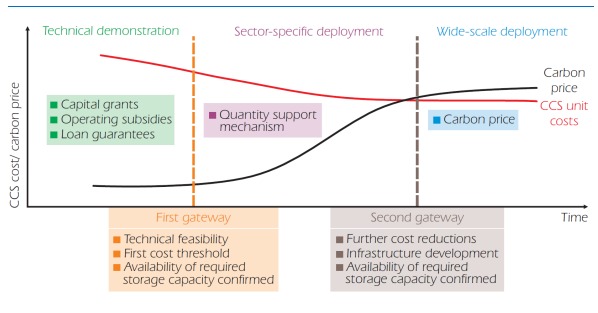

Developmental phases for CCS Policy framework

1) Public capital grants and opening subsidies to test the efficacy of technology

2) Determine how the CCS costs can be covered (partially through carbon price and support from a certain private/public sector) which involves implicit financing with subsidies.

From the government: CO2 contracts

From the private sector: portfolio standards

Through optimizing the cost distribution, it helps develop lowest-cost supply of CO2 for commercial usage.

3) Maturity stage involves long term infrastructure development through stable economy-wide carbon price

Figure 2 — Possible Gateways within a CSS policy framework

Motivations behind the CCS incentive (Reasons for policy intervention)

1) Externality: when a firm’s action causes impacts on others which it fails to take into account. ie: releasing excessive amounts of CO2 from fossil fuel combustion.

As more countries to join the CCS incentive, it helps increase economies of scale by improving cost effectiveness .. thereby reducing negative externalities

2) Public good: intervention helps incentivize the implementation of CCS policy which explicitly enable the diffusion of knowledge and from R&D demonstration projects throughout various nations

3) Imperfect competition: when the market is too concentrated with power where a few firms dominates, it affects price by having a few firms dictating output supply decision in the market. In the case of CO2 pipeline networks, one firm maybe unwilling to offer access to other firms on fair and reasonable terms. Consequently, with a restrictive access, the network would become too small of an extent and capacity, thereby driving up pipeline and storage prices.

4) Information asymmetry and imperfect information: investors are unable to discern good projects from bad projects. Given that information on CCS costs and performance is most probably unequally distributed, this would hold back investments in good projects.

5) Complementary markets: Imperfect coordination in output production and delivery could lead to an undersupplied capacity. This instance could occur if the vertically-integrated chain for CO2 capture and storage system are under different ownership such that investors are subject to numerous uncertainties and risk factors in the capture units and the storage space. They might be reluctant to commit funds into the CCS projects.

Based on these five factors, it is critical to have a set of policies that can correctly anticipate and minimize market failures.

References

Bruno, Zeller & Longo Michael. p.195 “Carbon Reduction Legislation in Australia” <<http://www.businessandeconomics.mq.edu.au/our_departments/accounting_and_corporate_governance/docs/publications/past_editions/volume_8/08Longo.pdf>>

Egger, Peter & Nigai Sergey. “Energy Reform in Switzerland, a quantification of carbon taxation and nuclear energy substitution effects.” <<http://www.economiesuisse.ch/de/SiteCollectionDocuments/20130130_Studie_ES2050_def.pdf>>.

“EU to link its Green House Gas Trading Permit System with Switzerland.” Council of European Union. December 20, 2010. <<http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/envir/118632.pdf>>.

“IEA, OECD Report on Switzerland’s electricity market reform, 2012.” <<http://www.iea.org/Textbase/npsum/switzerland2012sum.pdf>>.

“IEA review of Swiss Energy Policies.” International Energy Agency. July 3, 2012.<<http://www.iea.org/newsroomandevents/pressreleases/2012/july/name,28156,en.html>>.

“Switzerland challenging energy policy.” WNN. July 3, 2012. <<http://www.world-nuclear-news.org/EE-Switzerlands_challenging_energy_policy-0307124.html>>.

“Switzerland moves to join carbon market.” December 21, 2010. EurActiv. <<http://www.euractiv.com/climate-environment/switzerland-moves-join-europe-ca-news-500813>>.