Congestion issues are prevalent across many metropolitan areas in various nations. The Economic cost are captured in terms of monetary value, and reflected in the underlying negative externalities. These costs include: additional commute time, petroleum cost, increase in green house gas emissions, and disutility to commuters. In this blog entry, I will address the issue in the London Congestion Tax Policy.

The London congestion charge was introduced in February 2003. This policy is a taxation scheme specifically targeted within the Congestion Charge Zone (CCZ). It is levied on vehicles during peak hours on business days from 7 am to 6 pm.

Policy Coverage

The regions receiving charges involves the City of London, and the West End. In addition, charges apply to the various major roads: Pentonville Road, City Road, Old Street Commercial Street, and Mansell Street, etc. (Wikipedia.org).

In order to monitor for taxable vehicles, IBM utilizes an automatic number plate recognition technology (ANPR), and the Transport for London (TfL) is responsible for revenue collection.

By convention, there is price discrimination for vehicles paying at different times, and paying method. If vehicles pay by midnight on the day of travel, the charge would be £10 per day (Transport for London). However, if the charge is paid the next day, £12 is applied. Alternatively, vehicles would pay £9 charge, if it is registered with CC Auto-pay (TfL). This payment scheme incentivizes drivers to pay on time, and to use the auto-pay method to increase efficiency. Any failure on payment, would incur £120 charges (politics.co.uk, 2013). This would be reduced to £60 for payment in 14 days. However, there would be surge charges to £187 after 28 days. Auto-payment can be registered via TfL.

Tax exempted vehicles

Vehicle on roadside maintenance, registered cars fulfilling emissions of 100g/km or less of CO2, in addition to the Euro 5 standard, vehicles with nine or more seats, motor-tricycles are exempted from the taxation scheme (tfl.gov.uk, 21). There are refunds available to individuals who pay monthly or annual cash advance, alongside reimbursements to patients who are unable to travel by public transit. The exemption also extends to the firefighters, and the care-takers of patients who are driving vehicles (ibid, p.21). Residents close to or living in the Congestion Charge Zone can apply for a 90% discount via CC Auto-payment method (ibid. p.10). Free road access was also granted to hybrid cars (ibid p.25). However, the reformation of the discount policy on hybrid vehicles introduces a more stringent standard to hybrid, and electric car emissions. This reformation involves changing the original policy of discounts to greener vehicles in general, to a new Ultra Low Emission Discount Scheme. Hence, free access no longer applies to some hybrid vehicles.

Problem with revenue collection

In the Department of Transportation, the annual report mentioned the loss of tax revenue collection from this policy was approximately 26% due to the fact that the registered-vehicle owner was bankrupted, deceased, or untraceable (Wikipedia.org).

In addition, there are problems within the detection system reading foreign license plates (Police Executive Research Forum). By local law, foreign cars can only be used within the duration of six months prior to registering with the UK license plates. This condition applies to both visitors and non-residents (Vehicle Excise and Registration Act, 1994).

In addition, local newspapers reported incidence of duplicates of number plates in order to avoid congestion charges (BBC News, 2004). However, since TfL is a well-developed monitory body with adequate records for the number plates, it is difficult for vehicle owners to avoid congestion taxes.

Implementation Results

For the first six months of implementation, a survey from TfL indicated that the average number of cars in the central zone has been reduced by 60,000, which represents 21 percent decrease (Fahey, Trinity College Dublin). In addition, 50-60% of the reduction was attributed to the use of public transit, 20-30% was attributed with avoidance access to charged zones (Dunt & Stevenson). The remainder was attributed to access outside peak hours, cycling, increased car-sharing, and reduced trips (ibid).

The TfL is the authority responsible for congestion tax collection. In the fiscal year 2009/10, the TfL raised £148m in net revenue, which is then used for investment in improving the transportation system in London (Department of Transportation, 2013).

Hence, the Congestion charge results in displacement of automobiles.

Distributional Effects

Congestion tax is aimed at charging frequent drivers at traffic-sensitive zones.

I would infer that the Government has imposed a progressive tax, which implies as households or individual private income increases, there is a higher “vehicle ownership rates,” and “vehicle utilization rates. (Crawford, 3)”

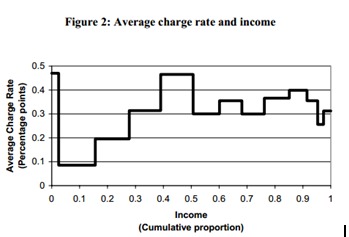

However, the regressivity/progressivity of the tax varies (ibid, 4). According to the Institute of Fiscal Studies, the nature of the tax largely depends on “whether the average level of income in households increases faster or less fast, than the ability to pay as we consider successively higher income bands. Thus, the average charge rate varies in income. (Crawford, 5)” As we examine the changes in average charge rates from lower to middle income bands, average charge rate increases (Crawford, 5). However, the charge rate diminishes as we move to households on the higher level of the distribution. We can infer that the tax is progressive from lower to middle income levels, since average charge rate increases with income. However, the progressivity diminishes in transition from middle income to higher income (ibid). Beyond the point of middle income, average charge rate declines at higher income level (ibid). Thus, the tax becomes regressive. Higher income pays a lower rate of charge.

Source: Crawford, Ian. “The Distributional Effects of the Proposed London Charging Scheme.” Institution of Fiscal Studies <<http://www.ifs.org.uk/bns/bn11.pdf>>.

In general, the Congestion Tax policy is effective. This is because the revenue is recycled towards road infrastructure development, which mitigates the tax burden in lower income households (Crawford, 6).

Evaluation of efficiency & Recommendations

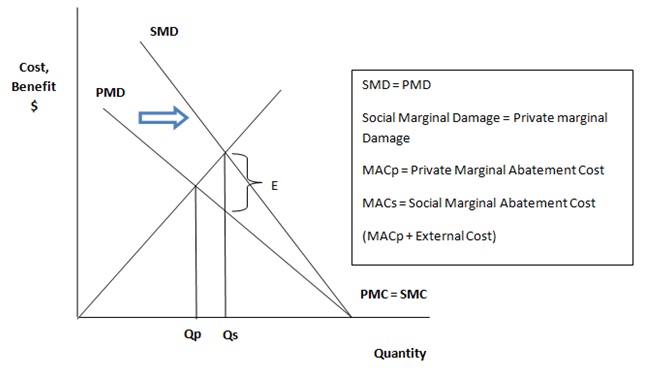

If the tax is effective, we would anticipate a reduction in road access. However, we are uncertain about the elasticity of road demand. A higher elasticity would result in larger reduction in demand, and the converse is true.

Vehicles from the commercial and public sector tend to be inelastic in terms of access to certain routes. In terms of vehicle size, it is not uncommon to have tractors, trucks, large SUVs on the road in these two sectors. Henceforth, when we examine the fuel economy associated with larger vehicles, a higher usage in petroleum results in greener house gas emissions.

On the other hand, vehicles of personal use, depending on the size of the household, and consumer preference on vehicle size, vehicle size varies from large movable dwellings, SUVs, vans to lighter private cars like mini cooper, and hybrids.

In my opinion, the daily access fee could be more effective if it is levied at different rates based on fuel economy, in addition to vehicle size. Given that the government has sufficient funding to invest on road infrastructure, Boris Johnson, the Mayor, should propose an investment project on weigh in motion systems (WIS) to levy on vehicles with higher mass. As a result, this new technology could enhance, not only efficiency in traffic flow, but also target specifically on vehicles with higher green house gas emissions.

In the near future, vehicles could have RFID tags to identify vehicles’ modelling year, which allows the TfL to compare the charged vehicle against a fuel economy database to determine the trip’s environmental impact.

Works Cited

BBC News. “Car Cloners Trying to Avoid Charges.” 24 June, 2004. 19 March, 2013. <<http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/england/devon/3837349.stm>>.

Crawford, Ian. “The distributional effects of the proposed London congestion charge scheme.” 20 March, 2013. <<http://www.ifs.org.uk/bns/bn11.pdf>>.

Dunt, Ian and Stevenson, Alex. “Congestion Charge.” 20 March, 2013. <<http://www.politics.co.uk/reference/congestion-charge>>.

Fahey, Colm. “Analysis of Road Pricing and a study of the feasibility on the M50.” 20 March, 2013. <<www.tcd.ie/Economics/SER/sql/download.php?key=86>>.

Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. “Vehicle Excise and Registration Act.” 18 March, 2013.<<http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1994/22/contents>>.

“London Congestion Charge Consequences.” 18 March, 2013.<<http://www.cchargelondon.com/effect.html>>.

Multiple Contributors. “London Congestion Charge.” 18 March, 2013. <<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/London_congestion_charge>>.

Police Executive Research Forum. January 2012. “How are innovative technologies transforming policing.” 18 March, 2013. <<http://policeforum.org/library/critical-issues-in-policing-series/Technology_web2.pdf>>.

Transportation For London. “Discount for exemptions, transport for London.” 16 March. 2013. <<http://www.tfl.gov.uk/roadusers/congestioncharging/6713.aspx>>

Transportation for London. “What do you need to know about congestion tax charging.” March 15, 2013. <<http://www.tfl.gov.uk/assets/downloads/congestion-charging.pdf>>.