Barkerville is a fascinating site because it is, all at once, a place of historical research and restoration as well as a recreational and tourist site. Archaeological excavations take place metres away from gift shops and ice cream parlors and even people who do research (like Yingying and Jimmy) double as tour guides and help welcome tourists and visitors. In a broader sense, Barkerville is also an ideas factory, a place where our understanding of BC history is literally manufactured and then disseminated through the education system. Barkerville, in other words, is about ideology.

What does it mean, then, to have the main stretch of Barkerville broken up by a “Chinatown gate” that says “歡迎到加列布“ -Welcome to “Jialiebu” or Cariboo.

Of course, those of us who have spent time in Chinatowns around the world are familiar with Chinatown gates. They mark a space as belonging to a particular ethnic or racial group and symbolize the cultural barriers between the Chinese and other communities. But as Jimmy told me when we were hanging out, the gate is a bit misleading for a few reasons:

(a) the typeface is quite modern – older gates would have more traditional calligraphy and probably wouldn’t say welcome to the Cariboo, but rather something more poetic to mark Chinatown.

(b) the most common term for Barkerville during the Gold Rush days wasn’t Jialiebu (or Gah-leet-boh) but rather 新金山 or Xinjinshan (Mandarin) or Sun Guum saan (Cantonese), which means “New Gold Mountain”. Not only does this title reflect the mythology of Gold Mountain (especially appropriate given why Barkerville was founded in the first place), but it also recalls San Francisco, which is still called “Old Gold Mountain” by many Chinese to this day. This places Barkerville in relation to its Southern cousin and reminds us that Barkerville used to be the second largest Chinatown in North America. But indeed, if almost half of the town’s population was Chinese, does it make sense to speak of Chinatown anymore?

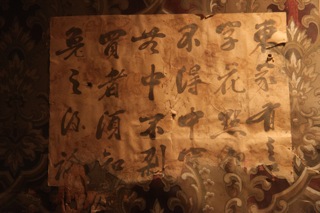

(c) It turns out that some of the buildings in the “European” side of town used to be in Chinatown. The Nichol Hotel, for instance, contains Chinese writing pasted on the walls that reveals its previous function as a gambling den. Why was the building moved “outside” Chinatown?

In sum, does building a Chinatown Gate help us understand the history of race relations in Barkerville (and indeed, BC) or does it impose our contemporary understandings of race relations onto a historical site? Why do we naturally assume that the Chinese lived apart from the rest of the community when, according to Jimmy, there is ample evidence of constant intermingling.

I am not trying to reimagine Barkerville as a racial relations paradise – a quick glance at all the anti-Asian legislation passed in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries tells us otherwise – but it does suggest that we have to keep questioning our assumptions. For example, when we call Chinese sojourners (they wanted to make money and leave), how does that make them different than anyone else in Barkerville? Who wasn’t trying to strike it rich (and in fact, remittances were also sent back to England from BC)?

Yingying mentioned that over the years, many of the old-timers came to realize that they would never go back to China in their lifetime. In fact, many of the Chinese buildings had signs that read “Tang Fang Di/唐藩地” or “Colony of the Tang People” (Tang people being a synonym for Chinese people) – so it appears that the locals once thought of themselves as a colonial settlement, a settlement within a white settled colony.

Yingying told this moving story of a Chinese man who lived for decades in Barkerville, and only took one trip, by foot, to the Fraser River and never even visited cities like Victoria or Vancouver. He died in Barkerville and his spirit still haunts the town.

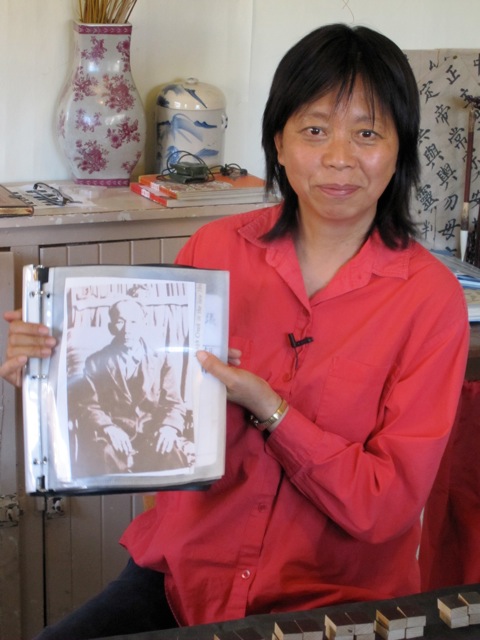

Other old timers eventually moved to other towns in BC and established families. During our trip, we bumped into Karin Lee, a well known Chinese Canadian filmmaker whose mother’s family once owned a major store in Barkerville. Their family house has now been restored with artifacts on loan from the family.

As we were driving to Prince George last night, the three of us kept talking about how common narratives about “pioneers” and “sojourners” hide the complex lives of those who lived during times of overt racial discrimination. How do we listen to those lives now, in 2009? As Walter Benjamin asks in “On the Philosophy of History, Doesn’t a breath of the air that pervaded earlier days caress us as well? In the voices we hear, isn’t there an echo of now silent ones? How does studying and indeed living Chinese Canadian history resonate in the lives of people like Yingying and Jimmy? Does someone with Chinese ancestry (even if not connected directly to the early community) react to such histories differently than someone with another background?

Categories: