The edition of the Bible Atlas is likely one of the earlier printed projects by N. & S.S. Jocelyn, given the quality of the work. Several physical anomalies point to potentially experimental, novice workmanship, not unusual for a work of this small size and market value.

The glue of the eleventh leaf can be seen on the front page of the Bible Atlas

The RBSC finding aid notes the physical description of the Bible Atlas as “9 leaves, imperfect copy spine sewn by hand,” but this is only half right: the chapbook-style work actually contains 11 leaves. It is slightly unusual for such a small book to contain an uneven amount of leaves, because it generally requires more work to assemble, as is the case here – the final page is glued in by hand to the back of the outermost leaf.

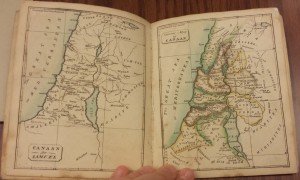

Side-by-side center spread

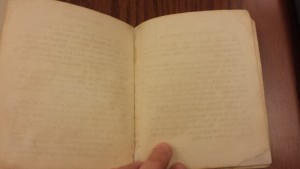

Back-to-back printing white spread

Some details suggest that the work may have originally intended to be half the length of the finished product, or that Nathaniel Joyce was still figuring out how to print and assemble works in sequential order. For example, the pagination started with the first map is discontinued halfway through the edition, at which point the printing also switches from the left hand side of the page to the right. As well, the final printed “Explanations” pages (the final of which is glued in by hand) are printed back to back, meaning that there is a full white page spread between the continuing segments. While the Atlas does indeed contain the “9 Maps” promised on the front cover, the irregular assembly of the Bible Atlas suggests that it may have been printed in 2 runs, or by a printer who was just learning his craft, or assembled hastily – or perhaps a combination of these things, or maybe some other reason entirely.

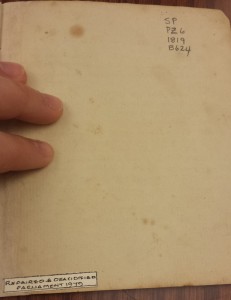

Inside back cover of the Bible Atlas; label bottom left, shelving information top right

Nearly 200 years later, the Bible Atlas has held up fairly well. While it sports a few stains and is generally quite tattered, the label on the inside back cover indicates that there was a repair job and deacidification completed by the cryptically named “Parliament” in 1979. Presumably it was this recovery which gave the copy it’s hand-sewn spine and what appears to be a card-mounted cover. While it would be nice to be able to see exactly what the copy was like when it was first printed, given that it seems like a novice printing of a penny-chapbook, the shape it’s in today is somewhat impressive; the likelihood of such a common book surviving at all is special, and the fact that it was restored for “better” preservation even more so – even if the process changed the colours or presentation of the work, there is something to be said for the value of its survival in any capacity.