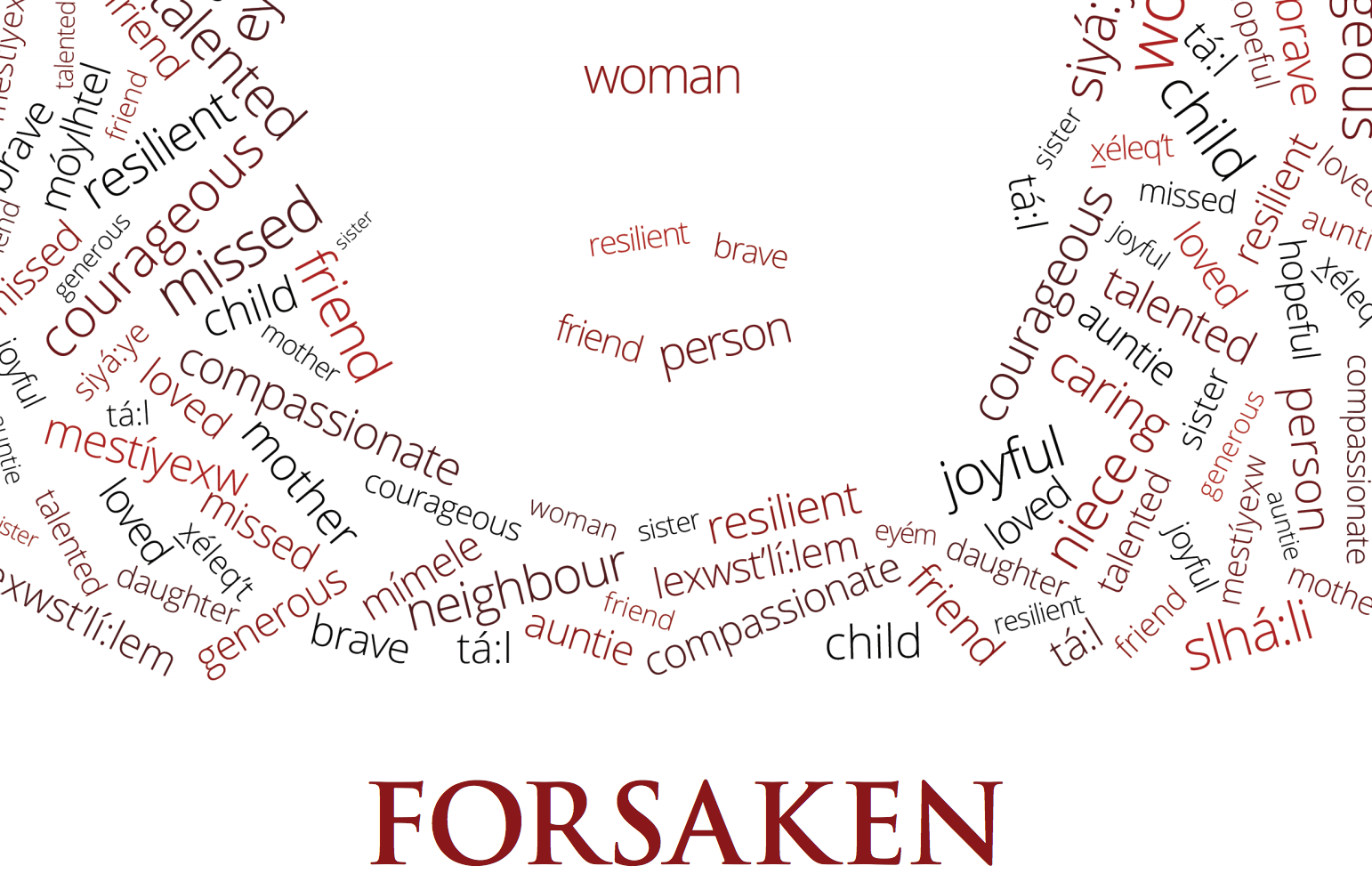

Portrayals of “Unseen and Unheard” Experiences in Wally T. Oppal’s Forsaken

In Soft Weapons: Autobiography in Transit, Gillian Whitlock brings forward the view that life narratives circulate as “soft weapons” that can “personalize and humanize categories of people whose experiences are frequently unseen and unheard” (3). While Oppal’s report does not fully qualify as an autobiographical work, it nonetheless sheds light on the personal lives of many missing women from the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver. Oppal, more significantly, achieves the exceptional goal of personalizing and humanizing the experiences of female figures who have so often been marginalized by society, and collectively and negligently characterized by the media as “sex workers.” In committing himself to the role as the speaker, however, Oppal essentially assumes an immense responsibility. In order to respectfully speak in the place of the voiceless and the deceased, Oppal must acutely be aware of the risks that may result from misrepresenting the fallen ones. The following post will look at the ways in which Oppal handles this hulking responsibility in an ethical manner, and how his voice and portrayals draw attention to larger social issues.

Oppal’s position as the speaker for Vancouver’s missing women is similar to the one that is assumed by Maggie de Vries. Not only do both strive to give a voice to the voiceless, both also come from more privileged backgrounds than the represented individuals and considered as outsiders of the Downtown Eastside community. These similarities mean one thing, and that is both speakers must take extra precautions in order to avoid being blamed for inadequately representing the missing and deceased; or worse, for failing to adhere to ethics and perpetuating stereotypes. Speaking for the deceased and voiceless is already a potent task; but for Oppal, he also needed to speak to those who did not wish to speak. As Oppal reveals, many family members of the missing women simply did not consent to releasing the life details of their loved ones. Although his duties are challenging, Oppal nonetheless maneuvers through the barriers in an effective and ethical fashion. He does so, in one way, by fully respecting the confidentiality requirements imposed by the law and family members. In the list of names, to illustrate, “Jane Doe” is used to protect the identity of a female victim. Unlike the complete representation of many other female figures on the list, Oppal does not add any kind of extra details to Jane so that he could falsely create some sort of equilibrium. Oppal’s brief but truthful description of Jane Doe demonstrates his efforts to abide by ethics in his portrayals, and never misrepresent anyone with information that is not sanctioned by the law or against the wishes of family members.

Forsaken has also succeeded in its reach of enlightening the society about the experiences of Vancouver’s marginalized community. Oppal helps us notice the trend that a woman’s suffering almost always comes with precursors. The experiences of most missing women portrayed by Oppal shift blame away from them and towards the deep scars left by abusive residential schools of the past. If the missing women themselves were able to avoid the horrific experience, their parents likely had not. The violent tendencies that parents pass down to their children, however, are just as detrimental, if not worse, for the abuse experienced by children of later generations came not from a stranger, but from those who were suppose to love them the most in this world. As many missing women came from disadvantageous backgrounds, their chances of survival were also slimmer, especially when professional help was out of reach. Part IV of the report, moreover, illuminates the lack of resources and treatment options faced by addicts and missing women when they want to quit drugs. Quitting an addiction requires great will power, and the impulse to relapse is strong and persistent. For that, access to treatments must be readily available to seekers. For Sarah de Vries, her heroin addiction gives her the option to receive prescribed methadone, an inexpensive pharmaceutical formula which effectively prevents withdraws. As Oppal cites a study conducted by Dr. Shannon, however, “long wait lists were cited as the primary barrier” to treatment facilities and methadone maintenance programs.

Oppal not only respectfully and ethically portrays Vancouver’s missing women in his report, his representations also powerfully broadens the view of the general public. Thanks to Oppal, we are able to see the endearing side of many missing females that few dominant media outlets offer.