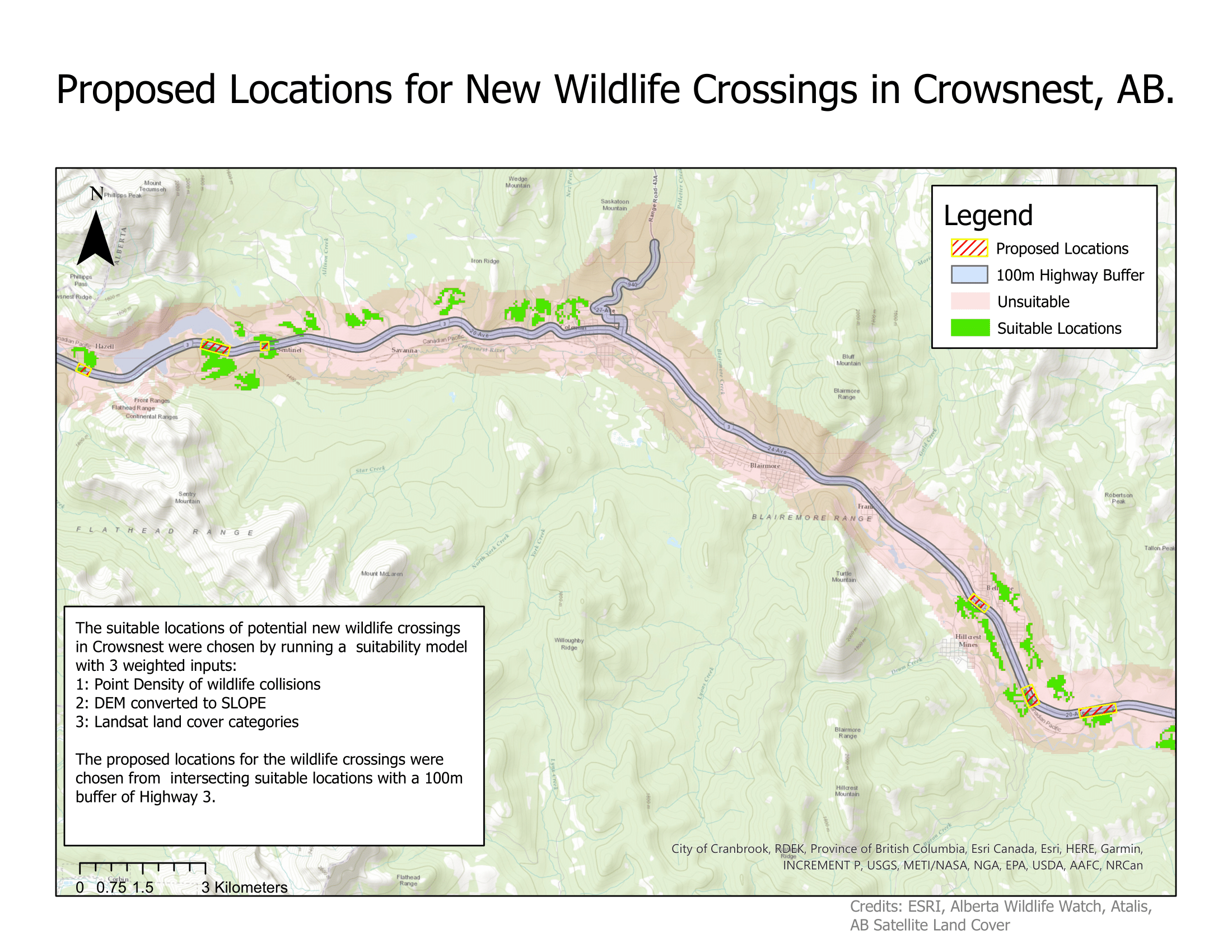

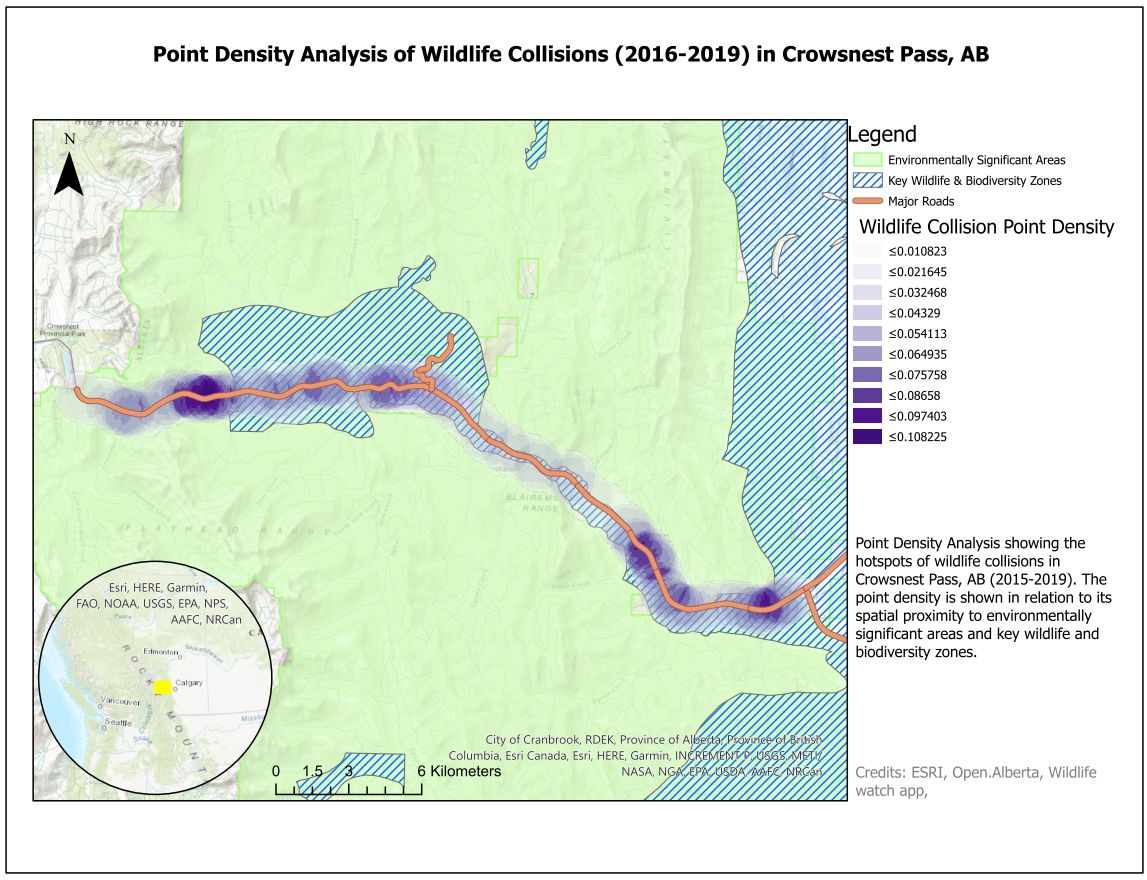

After calculating the suitability sites from the three weighted factors, we identified locations that overlapped between the suitable locations and our 100-meter highway buffer. Comparing the site suitability map with the point density analysis reveals that fitting sites for wildlife corridors strongly tend to be in areas with more traffic collisions, which makes sense given the weight of the criteria in our model. However, not every “suitable” area with a traffic density above .06 was fitting for a crossing. Take the areas northeast of Coleman as an example. While they meet hillslope, sufficient forest cover, and high point density of wildlife collisions, those areas do not fall within the highway buffer.

Most of the proposed locations fell outside of more urbanized areas, but one was directly south of Bellevue and north of Hillcrest Mines. Despite the area being surrounded by pavement, our methodology eliminated the possibility for the suitable zone to consist of water or concrete. This proposed location may help mitigate the threat of AVCs caused by wildlife moving into rural settlements and towns. While road development is known to make nearby areas less suitable for certain species like moose1, nonhuman animal activity in rural and urban areas is elevated due to attraction to food stores.2 Further stakeholder deliberation and on-site analysis of habitat, patch size and shape, natural processes, anthropogenic use, and observed patterns of fauna movement can help determine if that specific site is suitable for an underpass or overpass.

While advising the type of interventions needed beyond crossings is outside the scope of this study, it is important to note that some mitigation strategies are more effective than others. For example, animal detection systems, fences with underpasses, and overpasses are at least 30% more effective than most other mitigation measures, including population culling, warning signs, relocation, and fences with a gap and crosswalk.3 Policymakers and authorities also need to establish zones that allow for sufficient corridor space for wildlife. This can be difficult to pinpoint on width or height alone due to the various needs for space between species.4 Thankfully, all suitable areas that fall within the highway buffer were greater than or approximately equal to half of a kilometer.

Citations

1Shanley, C. S. & Pyare, S. (2011). Evaluating the road-effect zone on wildlife distribution in a rural landscape. Ecosphere, 2(2), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1890/ES10-00093.1

2Ditchkoff, S. S., Saalfeld, S. T., Gibson, C. J. (2006). Animal behavior in urban ecosystems: Modifications due to human-induced stress. Urban Ecosystems, 9, 5-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-006-3262-3

3Miller, T., Jambor, M., & Wasniak, D. (n.d.) Design Considerations for Wildlife Crossings. Contech Engineered Solutions. https://www.conteches.com/knowledge-center/pdh-article-series/design-considerations-for-wildlife-crossings

4Fleury, A. M. & Brown, R. D. (1997). A framework for the design of wildlife conservation corridors with specific application to southwestern Ontario. Landscape and Urban planning, 37(3), 163-186. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(97)80002-3