Question: “In this lesson I say that it should be clear that the discourse on nationalism is also about ethnicity and ideologies of “race.” If you trace the historical overview of nationalism in Canada in the CanLit guide, you will find many examples of state legislation and policies that excluded and discriminated against certain peoples based on ideas about racial inferiority and capacities to assimilate. – and in turn, state legislation and policies that worked to try to rectify early policies of exclusion and racial discrimination. As the guide points out, the nation is an imagined community, whereas the state is a “governed group of people.” For this blog assignment, I would like you to research and summarize one of the state or governing activities, such as The Royal Proclamation 1763, the Indian Act 1876, Immigration Act 1910, or the Multiculturalism Act 1989 – you choose the legislation or policy or commission you find most interesting. Write a blog about your findings and in your conclusion comment on whether or not your findings support Coleman’s argument about the project of white civility.”

“The Indian Act is purposely designed to assimilate us. It is meant to sever the generations. The Act is working its purpose, through provisions concerning land, elections, membership, commerce and education. It cuts us from those future relationships. We can not take account of the seventh generation if the Indian Act continues to remove them from us. […] I also look for guidance in the other direction, seven generations back. My grandmothers and grandfathers also have something to teach me about eliminating the Indian Act.”

— John Burrows,

Seven Generations, Seven Teachings – Ending the Indian Act (3)

For thousands of years, Indigenous people lived on the lands now known as Canada without the legislation of the Indian Act. ”As First Nations we lived free from its constraints. We observed laws that encouraged us to be wise, humble, respectful, truthful, brave, loving, and honest in our dealings with others. Other people did not define our citizenship. We held our land in accordance with our own traditions.” (Burrows 1).

Most Canadians are vaguely familiar with the Indian Act, whether they know it or not. Canadians know that many Indigenous people live on reserves (which are legislated through the Indian Act). Canadians know that many Indigenous people pay different taxes (because of their Indian Status, which is legislated through the Indian Act). Canadians know that Indigenous people face injustice and inequality (much of which is a product of violence inflicted through the removal of Indigenous people from their homelands, restrictions on their rights to move freely, and misrepresentation or lack of representation in government- a result, in large part, of the Indian Act).

To begin, see this meme project on the Indian Act for a straightforward summary with dates of some of the harmful policy enacted on Indigenous people through the Act, much of which is still in effect today.

The Indian Act, 1876

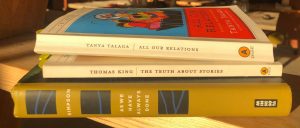

Indigenous literature, by Tanya Talaga, Thomas King and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, to support decolonial learning. All texts referenced in this blog post.

The primary concern of the Indian Act, first enacted by the Crown in 1876, is “Indians and land reserved for Indians” (Coulthard). To be clear, this legislation was imposed on Indigenous people and lands for the benefit of the colonizers- the benefit of Canada.

In her book As We Have Always Done, Anishnaabe scholar Leanne Simpson explains: “colonizers wanted the land. Everything else, whether it is legal or policy or economic or social, whether it was the Indian Act or residential schools or gender violence, was part of the machinery that was designed to create a perfect crime – a crime where the victims [Indigenous people, as well as colonizers/ settlers] are unable to see or name the crime as a crime,” (Simpson, 15).

The Indian Act came as a result of the Gradual Civilization Act, 1857, and the Gradual Enfranchisement Act, 1869, both with the goal of taking away Indigenous rights and enfranchising or assimilating Indigenous people into the Canadian body politic (but only those deemed adequate – read: male, able to read and write in English or French, deemed “civil” according to non-Indigenous Indian Agents).

The Indian Act, a product of the aforementioned acts, had and has the ultimate goal of assimilation “by eliminating all aspects of Indian difference: spiritual, economic, political, gender and land relations,” (Coulthard). As Tanya Talaga writes, it is “a federal statute that governs every aspect of an Indigenous person’s life, from land management to education to cultural ceremony and even status and identity. It is a registry of all First Nations people in Canada. Those who have proven status – based on the Government of Canada’s strict criteria – are given a ten-digit number signifying that they have been sanctioned as official Indians and are kept on a roll. The policy also kept First Nations on reserves allocated on Crown land and sanctioned the cruel removal of children from their families, their communities, to be sent to one of the 139 Indian Residential Schools across the country. The Indian Act has been described as a form of apartheid, controlling Indigenous people’s lives to this very day,” (Talaga 64).

The Indian Act was created to exercise colonial control on Indigenous people, and domination over lands and governance. “The Indian Act makes it easier to control us: where we live, how we choose leaders, how we live under those leaders, how we learn, how we trade, and what happens to our possessions and relations when we die,” (Burrows, 5).

In addition to imposing the reserve system which confined Indigenous people to small tracts of land, the Act also imposed Status which is a federally-mandated determination of who and who is not Indigenous. Until 1985 when Bill C-31 came into effect, Indigenous women who married non-Status men (including Metis or Inuit), lost their status, their children’s status and rights to live with their communities. The effects of this legislation are still deeply felt by women and their children who were pushed out of their communities. Additionally, women were excluded from political participation under the Indian Act from 1876-1951 (Simpson 105), with detrimental effects to their Indigenous governance models, many of which were matriarchal pre-Indian Act. I can barely begin to summarize the violence imposed on women, queer and Two-Spirit people through the Indian Act here or its lingering effects on Indigenous women, queer and Two-Spirit people today. Leanne Betasamosake Simpson offers a powerful summary in her book As We Have Always Done, in the chapter titled The Sovereignty of Indigenous Peoples’ Bodies. Her decolonial work needs to be upheld all across the lands we know as Canada. Please take time with her words.

Back to the Indian Act…

For those who remained on reserve, governance shifted dramatically under the Act which imposed a Band and Council system. Shin Imai elaborates: “in order to ‘assimilate’ Indians, the Indian Act gave the government the power to override traditional methods of governance. In the case of Six Nations in Ontario, for example, the government used its power to overthrow the traditional Haudenosaunee Council in 1924 and replace it with a Chief and Council elected under the Indian Act. This was against the wishes of the majority of the members of Six Nations. Even, today, the vast majority of the residents of Six Nations refuse to participate in Indian Act elections,” (Imai 4).

Additionally, the Minister of Indian Affairs had the power to overrule Band Council legislation without reason, and in some cases, still can today. In 1995, the government of Canada affirmed the inherent right for self-government of First Nations, done on a case by case basis, which is often costly and rarely favourable for First Nations. This came at the time of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal People, calling for new relationships between Indigenous people and Canada, in part, a result of the Meech Lake Accord and the Oka Crisis. RCAP recognized nearly 90 provisions where the Minister of Indian Affairs has powers over the Band and Band Council (Imai).

Self-governance is too often defined or restricted by colonial terms and comes after a costly, lengthly court procedure where Indigenous nations need to prove their land base and traditional governance under colonial definitions, but it is what Indigenous communities need and many have reached or are working towards. “Negotiated self-government agreements remove much of the power of the Department of Indian Affairs and require more accountability by Chief and Council to community members. Even Bands under the Indian Act are moving in that direction […] [by] creating their own custom election codes,” (Imai 10).

Under the Criminal Code of Canada and United Nations definitions, some Indian Act policy is considered genocidal. For example the forced attempts to kill a culture by removing women (repealed in 1985 under Bill C-31) and banning potlaches, sundances, and other cultural ceremony (ending in 1951).

We must recognize Indigenous resilience in the face of ongoing settler-colonial violence and genocidal practices. Simpson reminds us that, even when outlawed, cultural practices persisted. She says, “our cultural practices were hidden from the surveillance of Indian Act authorities because they embodied our political practices, because they were powerful, and regenerating language, ceremony, and land based practices is always political,” (Simpson, 50).

Dismantling the Indian Act

Decolonization: “transforming the colonial outside into a flourishment of the Indigenous inside.”

— Leanne Simpson

Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back

“If the Indian Act is going to be eliminated in a way that benefits First Nations people, goodness must lie at the root of such change.”

— John Burrows

Seven Generations, Seven Teachings – Ending the Indian Act (8)

“As a father of two daughters, he [Alvin Fiddler, Nishnaabe Aski Nation Grand Chief] wants to live to see the day when their existence is no longer legitimized by assigned numbers or dictated by the federal government, effectively making them wards of the state.

Alvin believes it is not up to the government to determine who is Indigenous and who is not.

Belonging is not theirs to give.”

— Tanya Talaga

All Our Relations (198)

Trudeau’s White Paper, 1969

At first glance, the White Paper may have appeared productive. It promised to eliminate the Indian Act, recognize First Nations contributions to Canada, offer services to Indigenous people equal to those of all Canadians, and transfer control of Indigenous lands to Indigenous people as private property. However, the proposed “solution” failed, as it did not guarantee specific rights (specifically collective title to the land) nor unique (sui generis) status to Indigenous people and communities and was not created collaboratively with Indigenous people- rather, it was yet another effort at assimilation.

Comprehensive Treaty Process, 1973

Established to address Indigenous land rights, bands who complete the Comprehensive Treaty Process are no longer under the jurisdiction of the Indian Act (such as the Nisga’a whose territories I’m writing from today). The ultimate goal, however, was to open up clarity for Canada to pursue economic development mainly through extraction on Indigenous lands through the process of extinguishment of Indigenous people from their lands. To make this process very difficult, Canada’s expectation of proving Aboriginal title (maps, written documentation) do not always align with Indigenous ways of knowing (oral histories, toponyms). It is through lengthly court battles, such as the Calder Case, that nations such as the Nisga’a have had their oral histories recognized as legitimate and been able to sign modern treaties.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2007

Included in this commission, with a focus on bringing light and justice to the harms of the Canadian residential school system, were 94 calls to action, many of which are being worked towards nation-wide today. However, there appears to be a selectiveness with the calls to action; a preference for reconciliation, too-often defined by non-Indigenous institutions, and a forgetting of the importance of truth; a preference for the uplifting of cultures, rather than the return of land and rights, such as what would be possible through a legally-binding UNDRIP (the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People).

The current government refers correctly to the Indian Act as a patriarchal piece of legislation, yet it hasn’t been dismantled. Today, Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government has moved away from explicit domination, to more subtle acts of selected recognition of Indigenous self-determination and self-governance. Under Trudeau, the country’s first Indigenous Justice Minister, Jody Wilson-Raybould, was demoted in her attempt to uphold justice.

In so-called Canada, where the violence of imposed white civility through the nation-building project is alive and well, we can learn from Nelson Mandela who said, “To be free is not merely to cast off one’s chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others.” This includes the surrender of settler-Canadian land, power, and privilege to Indigenous people, which includes the dismantling of the Indian Act. This work involves deep listening, patience, and a willingness to let go of power so Indigenous people can take what is rightfully theirs – their land, their bodies, their fullest sense of agency. Settler-Canada must trust that justice will work out better for us all- and Indigenous people must know and feel the justice they’ve always deserved.

(note: Listen to MediaIndigena Ep. 124 & 125 to learn about Trudeau’s “solution” to the Indian Act – the Indigenous Rights, Recognition and Implementation Framework – a set of laws and policies that would indefinitely change Indigenous rights in the country. Hayden King and Shiri Pasternak offer a strong primer and critique of the policy which was drafted in collaboration with Jody Wilson-Raybould.)

Works Cited

Burrows, John. “Seven Generations, Seven Teachings – Ending the Indian Act,” National Centre for First Nations Governance. May, 2008.

Canada. “Indian Act”. February 14, 2019. Accessed at: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/I-5.pdf

CBC Books. “As We Have Always Done – Leanne Betasamosake Simpson.” August 14, 2017. Accessed at: https://www.cbc.ca/books/as-we-have-always-done-1.4433527

CBC Radio. “Years after Oka, Mohawk activist Ellen Gabriel says Indigenous people still treated as ‘dispensable’.” November 13, 2018. Accessed at: https://www.cbc.ca/radio/asithappens/as-it-happens-50th-anniversary-special-friday-1.4903581/years-after-oka-mohawk-activist-ellen-gabriel-says-indigenous-people-still-treated-as-dispensable-1.4903609

Coulthard, Glen. “FNSP Intro Lecture” (Georgia’s personal notes). 2014.

Galloway, Gloria. “Elijah Harper, First Nations leader who brought down Meech Lake, dies at 64,” The Globe and Mail. May 11, 2018. Accessed at: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/elijah-harper-first-nations-leader-who-brought-down-meech-lake-dies-at-64/article11988959/

Hamilton, Taryn. “Indian Act Meme Project,” Otahpiaaki. Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. Accessed at: https://www.ictinc.ca/indian-act-art

Harp, Rick. “Is Canada’s newest solution to the Indian Act worse than the problem? (With Hayden King and Shiri Pasternak)” MediaIndigena: Ep. 125. July 26, 2018. Podcast. Accessed at: https://mediaindigena.libsyn.com/ep-125-is-canadas-newest-solution-to-the-indian-act-worse-than-the-problem-part-2

Imai, Shin. “The structure of the Indian Act: accountability in governance.” National Centre for First Nations Governance. July, 2007.

Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake. “As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance.” University of Minnesota Press. 2017. Print.

Talaga, Tanya. “All Our Relations: Finding the Path Forward.” CBC Massey Lectures, Anansi Press. 2018. Print.

Tyee Staff. “On the record: Jody Wilson-Raybould’s Devastating Testimony of the SNC-Lavalin Scandal.” February 27, 2019. Accessed at: https://thetyee.ca/News/2019/02/27/On-the-Record-Jody-Wilson-Rayboulds-Devastating-Testimony-on-the/?utm_source=facebook&fbclid=IwAR0FjEFiu-3_MVSU7geoXzDDycSz-jWw2ZonnPbFfNnIZlZK7Dm4YVHtL3Y