Welcome back everyone for the 2nd feature of our 3-part saga on the seminal work of English poet George Wither, his Collection of Emblemes, Ancient and Moderne. Last installment we went over Wither’s abrasive and shifting careers in poetry and politics, so this time around, we’ll take things to a more corporeal level and take a look at the book itself.

Before we start on the history of the edition made available to us by UBC’s Rare Books and Special Collections, it’s only right we should investigate other existing editions of Emblemes. To this effect, the website of the Antiquarian Bookseller’s Association of America (ABAA) yields three exact matches.

The first is a much more recent edition, published in 1973 by the Scolar Press in London. It is identified as a Facsimile reprint and is described as “a tall quarto in brown cloth with gold and black gilt in vinyl cover” (ABAA). It is a reproduction of the 1635 original by Wither and is listed as selling for $80 by Second Story Books.

The second match is much older and shows signs of wear. It was published in 1635 by A.M. for a Robert Allot. A quick Google search reveals that Allot was a London bookseller and publisher active from around 1625-1635. More specific information on him is lacking as he is often confused with the earlier scholar Robert Allot who was a minor poet and fellow of St. John’s College in Cambridge (uncle to the former Robert Allot). This edition is in hardcover and tightly bound but missing several pages, and of the 200 original emblems, only 164 remain. The suede cover is rubbed and worn and the book itself has clearly sustained more damage and wear than our edition in the UBC RB&SC. On some pages there is evidence of attempts to repair it including but not limited to the restoration of margins and tape along tears. This edition, despite the damage, is selling for $3500.

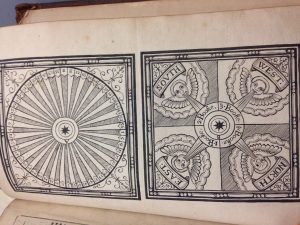

The third match is much more recent as it is a 1973 facsimile reprint of the Scolar Press facsimile of the 1635 original edition. It is a hardcover and the illustration on it is the same as the image in the latter pages of the 1635 edition, where a compass point is designated to each of the four books in Emblemes.

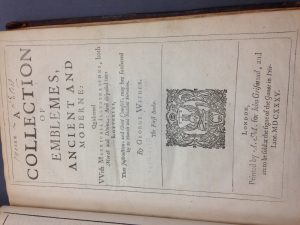

There are several clues as to the specific edition’s provenance in the book cards. One lists the attributes of the book, revealing that our edition was also printed by A.M. (similar to the second match on ABAA) but rather than Robert Allot, ours is for Henry Taunton, also in 1635. The information on this note contradicts the information on the frontispiece, where the print is credited as being for a John Grismond. However, both editions match in date of print: 1635.

Compared to the other editions listed on ABAA, UBC’s edition is in fairly good condition. There are a few tears but mostly due to creases in the pages. There are a few holes in some of the pages, raising questions of whether our edition has suffered bookworm experience (except, well, this one). Like most other editions, ours is in Broadsheet printing. There seems to be no deviations in the print materials although the book consists of several hundred pages. The binding is slightly flaky but due to restoration efforts in 1988 where the spine was rebacked and the leather repaired with Japanese leather and paste, the book’s condition remains intact. The font is Roman, with frequent use of Italics, with the increased contrast and vertical stress being typical of 17th Century fonts (Gaskell’s New Introduction to Bibliography). The binding is embossed goatskin (‘morocco’), with 4 large stitches bulging in the spine. Only emblem pages are numbered.

Pencilled into the front cover of the UBC edition is a mostly illegible handwritten note regarding this edition as a facsimile, alongside a price note of £125 . There were two documents in the front cover of the book, in addition to the aforementioned cards in the back. The first appears to be a clipping from a catalogue or auctioneer’s notice, listing the attributes of the book (Fine Copy. Folio. Straight grain morocco, gold lines on side, full gilt back, gilt edges. [line break] London, Printed by A.M. for Henry Taunton, 1635). The second is from one John to another John, dated 1945 and identifying the artist behind the engravings as “a Fleming, Jon Utrecht, a man of letters and patron of art”, who also apparently illustrated an equestrian manual for Louis XIII. This is follows by the qualification that “All (probably false) information [is] from Horace Walpole’s Catalogue of Engravers” – a noteworthy consideration, considering the well-known contributions of Crispin Van de Passe.

There is some (heavily-faded) marginalia on the title page, presumably a name, with the surname resembling ‘Eliot’. There are also several watermarks, on 2nd and 3rd pages of the dedication to Charles and Mary, the 1st title page, the explanation of the dedication, and the index. The bottom corners of several pages near the back of the book show signs of water damage, and one of the pages in the index is torn.

The general condition of most of the pages is good, and Van de Passe’s artwork is in fine condition. The etchings display a good grasp of detail (which we’ll delve into with our single-page analysis) and the quality of the printing ensues that the accompanying text is legible. As mentioned before, a great deal of the artwork in the book was the work of Crispin Van de Passe, a Dutch engraver of some renown. Many of the emblems are memento mori and the majority bear religious overtones, with some, such as Emblem 16, alluding heavily to the growing mindset of Puritan insurrection, in which Wither would later take part. Others, however, directly celebrate the office of kingship, such as Emblem 32, indicative of the Jacobian-Spenserian idealism championed by Wither in his earlier days (link to higher-definition photos).

Midway between these sentiments, indicative of the simultaneously subversive and reactionary tendencies upheld by Wither, is the page to which we shall devote our grandest skills at analysis (what some naysayers may call nitpicking) for our third and final segment on Emblemes.

Wriggling into the new dawn,

The Bookworms