Welcome back to our tripartite analysis of largely-forgotten poet-provocateur George Wither’s Collection of Emblemes, Ancient and Moderne. To cap off the series, we have our own analysis of one of the more indicative emblems in the collection, Emblem 12: ‘As, to the World I naked came / So, naked-stript I leave the frame’

To address the obvious, the image in this emblem is interesting, which is to say quickly approaching silly. There is a naked man, ascending away from scattered swords, orbs and crowns, as the sun looks on with a cocked head. Referring to this image as (on its own) as ‘curious’ is somehow both euphemistic and dysphemistic.

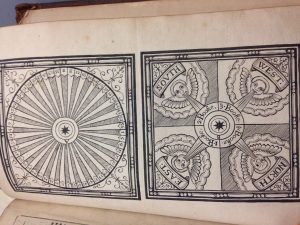

Technically speaking, Van de Passe’s etching is excellent, with very fine detailing, from the straight lines emanating away from the sun to the slight curvatures in the clouds. The lining of the image is, however, a weak point, with the lines appearing slightly irregular (especially those around the page number and the text of the emblem), as if very steadily hand-drawn. The lettering which circles the emblem also situates the figure just below an alpha and an omega, a still-resonant symbol of life and death. The sun and the moon correspond respectively to these in the image (the latter very faintly visible over the nude man’s should, reader’s right).

As with most of the volume, italics are generously applied for emphasis in both the emblematic phrase and the verse below. In the latter respect, the more seditious aspect of Wither’s contribution involves the characterization of the objects scattered before the ascending figure: a prince’s coronet, two iterations of a king’s crown, a papal mitre, an orb of state, a scepter and two longswords.

This imagery is resonant across Wither’s religious and political convictions, respectively Puritanical and Jacobian Spenserian, both of which he maintained to a degree at the time of printing. He would go on to serve the throne, but his eventual role in Cromwell’s government can be foreseen in some lines of his verse, such as lines 7-8: ‘Nay, what poore things are Miters, Scepters, Crownes / And all those glories which men most esteeme’. Furthermore, in 10-11, the wealth of royalty is characterized, which will ‘blinde / with some false luster [man’s] beguiled sight’. This Puritan disavowal of ritual casts the images of both kingship and Catholic ecclesiarchy in a pejorative, rather than simply superfluous light. It is not at outright seditious as Emblem 16, but certainly does not acclaim the office of kingship in the same manner as Emblem 32. The latter part of the poem is addressed to God, and takes the form of Wither’s personal praise to the Almighty, including credit for his survival of the plague. As Wither, like many of his contemporaries (i.e. John Milton) saw the plague of 1625 as a religious reckoning, it is unsurprising that it should be conjured as an example of, if not God’s goodwill, then man’s powerlessness in the face of its absence. Wither closes the poem on this sentiment, to ‘Forsake my Selfe for love of thee’, an adequate conclusion upon the emblem’s premise.

Wither is not a well-remembered poet and it is heavily debatable as to whether or not he was a good one (we may have given indications as to where we stand on this matter). The value of his writing, especially in the form of the Emblemes, is rooted in the presentation of his personal convictions as a microcosm of the unrest that would come to spark the English Civil War, including the shock of the plague, waning trust of monarchic ritual, persecuted temperament and connections to the Calvinistic Dutch. The nature of emblems is allegorical, and in that regard, this well-weathered copy is an apt preservation of the influences and anticipations which shaped much of the religious, political and literary thought in 17th Century England.

Wriggle on, friends

The Bookworms.