NOTE: This is a draft; critical feedback, comments, and questions are very much welcome! (Leave a reply or e-mail wolf@cs.ubc.ca.)

If you’re in academia and teaching is an important part of your job, then you’ll probably need a teaching portfolio for promotion or tenure at some point. Unfortunately, despite the fact that you have dozens/hundreds/thousands of students, teaching is often a solitary endeavor, especially compared to research. How, then, do you compellingly document your teaching experiences and innovations to others?

Here’s my advice, much of it inspired by my long-ago participation in the Engineering Teaching Portfolio Program offered by U. Washington’s Center for the Advancement of Engineering Education.

I wrote this advice as I was drafting my tenure packet—CV and portfolio—and promotion packet. The tenure packet from Sep 2008 was for promotion from “Instructor I” to “Senior Instructor” at UBC and, of course, for tenure. The promotion packet from Sep 2013 was for promotion from “Senior Instructor” to “Professor of Teaching”, a somewhat unexpected process since the rank did not exist when I began at UBC. For context, check out UBC’s tenure and promotion policies. The guidelines for promotion to Professor of Teaching have the most detail, although they were published well after my tenure case.

Prelude

Both my tenure and promotion packets are bulky but designed to be skimmed. I aimed for a “multi-resolution” packet that offers busy readers a short, sweet summary they can read, skipping the rest, but with hooks available to dive deeper, all the way down to evidence (artifacts of teaching, evaluation records, research citations, etc.) supporting the claims I make in my portfolio.

One minor caveat for non-Computer Scientists: Conference publications in CS are at least as prestigious as journal publications (and often more so). More broadly and importantly, you’ll want to adjust disciplinary or cultural issues like this for your own context in both my packets and my advice!

Finally, be aware that the packets are written to make me sound like I walk on water. It’s all true mind you, but spun to the max. Don’t get intimidated; you can sound like you walk on water, too!

Beforehand

Here are a few steps you can take from the start of your teaching career to prepare yourself for your tenure or promotion case.

1. Be a pack rat. Save everything and file it away. Meeting agendas, notes from students and colleagues regarding your teaching, links to interesting student artifacts, etc.

2. Write, write, write. Write a “post mortem” after each class describing what worked well and poorly, write analyses of your exams (how and why you planned them and how they turned out), write any commentary on your own teaching that you can motivate yourself to put down.

Doing it all the time will help you tremendously as a teacher. Doing it at least sometimes and filing it away will be invaluable for your portfolio.

3. At least once a year—merit review, anyone?—write out a one paragraph story of each major teaching-related effort you make, like course design, new pedagogical approaches, student research supervision, and so on.

My mentor Paul Carter suggested this to me and suggested my CV as the place to keep it. Using this approach, your CV recaps points in your promotion portfolio… but it also makes the CV stronger and forces you to write bits and pieces of your portfolio every time you update the CV. At my promotion, I received strong advice to brutally trim this in the submitted version, but the same text migrated over to the rest of my packet!

Writing the Portfolio

The writing process itself can take a while on the calendar and a fair number of hours. Get started early, and try out these steps. I started a year or more in advance with the first step below.

1. Review some other people’s portfolios. When I say “review”, I mean review like you would a conference or journal submission. Question how and whether they’ve accomplished their main points and mark the document up with recommendations. If the author is still working on their portfolio, this is peer feedback, but it’s worthwhile regardless so that you can discover what makes an effective portfolio.

2. Write three crappy teaching philosophy statements, with three totally different philosophies. Don’t worry; they won’t go into your portfolio. Their purpose is to encourage you to think creatively about what you’ve accomplished as a teacher and why you did it.

3. Make a list of artifacts you can use as evidence of your successful teaching:

- Your favorite stuff that you remember.

- Anything that catches your eye as you peruse your pack-rattish hoardings.

- Things that click with the crappy philosophies you’ve written.

- At least one example of every type of thing (lecture, assignment, interactive exercise, demonstration, exam, etc.) you’ve ever put together for a course.

- Examples of cases where you did not do that well, especially where you have the evidence you used to discover the problem and steps you took to resolve it.

4. Throw your crappy teaching philosophies away.

5. Make an “affinity diagram” of your artifacts. Put a brief description of each artifact on a post-it note and then stick the post-its on a whiteboard arranged into related groups. Look for ideas about your teaching in those groups. Is there a cluster of artifacts that are all about bringing your research ideas into the classroom? A cluster about encouraging students to take responsibility for their own learning? A cluster about current cultural references? Whatever.

Give each cluster a title—grab a whiteboard marker, circle the post-its, and write a name next to the circle—and take a picture of the diagram you created.

Now, repeat this process a couple more times but intentionally make very different clusters. Hopefully those crappy teaching philosophies you wrote have keyed you to be able to view your teaching from very distinct perspectives.

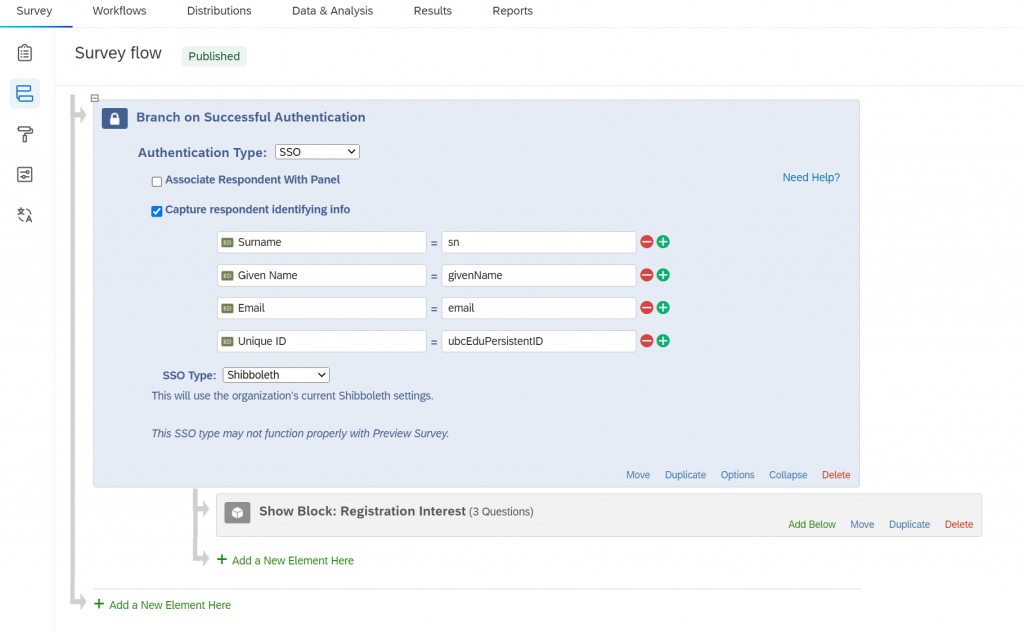

Here’s a summary I drew while creating my tenure packet of some of the groups in my affinity diagrams:

Circled nodes are cluster titles; uncircled nodes represent artifacts.

6. The cluster titles you created represent new themes for a new teaching portfolio developed bottom-up from—and supported by—the evidence you’ve collected to build your portfolio. Plop down the cluster titles as section headers in a text editor with brief notes of its artifacts below each one.

My teaching portfolio for tenure grew out of the clusters in the image above. Compare those circled nodes to these section headers from the portfolio: “Motivated Learners”, “Active, Reflective, Social Learners”, “Reflective Teaching”, and “Practical, Respectful, Efficient Teaching”.

7. Flesh out, paring back to the artifacts that really make your point. The best artifacts are the ones that look good in themselves and also support multiple clusters effectively, so you don’t need quite as many to tell your story.

8. Now, write a good teaching philosophy to pull it all together into a coherent story.

When you’re done, you’ll have a coherent story that describes the most important elements of your teaching with strong evidence (your artifacts) backing up each point in the story. The artifacts themselves can be appendices; your audience doesn’t need to read these because your philosophy statement will reference them in context whenever they’re needed.

Letter Writers

You may also need to recommend letter-writers for your case. For my tenure case, I proposed six letter-writers, a minimum number of whom (perhaps 2?) were guaranteed to be asked as letter-writers in my case. My department independently chose the remaining letter-writers. (If you submit a list, know whether their choice is independent of or exclusive with your list! If their list must not overlap yours, then you may want to avoid putting all your best prospects on your list!)

This process was challenging, perhaps more so for assessing teaching than research. After all the main products of research are intentionally very public. In the end, I made a long list of candidates who I could be reasonably confident were familiar with some aspect of my work, using the sections of my teaching portfolio to guide my brainstorming of names. Then, on advice from my mentors, I added Canadians in prominent undergraduate management or advising positions and filtered out almost everyone who was: (1) not tenured/promoted themselves yet, (2) too well-known to me (e.g., had co-taught with me, co-organized a major event, or co-published something more significant than a panel), or (3) did not have a PhD.

Finishing Up

Now, get and give lots of feedback until you’re ready to send it off. Look for feedback from mentors, peers, colleagues, and anyone involved in the tenure and promotion process to whom you have access!

There’s one more point that’s easy to miss; don’t miss it. Creating your portfolio this way takes a great deal of time and work. One benefit of the work (hopefully!) is tenure and promotion.

But you should also benefit by gaining insight into what matters to you in your teaching and what you want to do next. Read over this document with fresh eyes thinking about where you want to go in your teaching now that you’ve sent your case off. After all, you’re getting tenure or, to be pessimistic, you’re about to be denied it. In either case, now’s the time to try something risky and innovative that takes your career to the next level!

Links

Here are links to the materials I submitted for tenure and promotion:

Here are links to a few other materials that helped me as I made my packets or that I’ve found interesting since then.

- Jodi Tims’ SIGCSE slides on promotion and tenure from the 2016 New Educators Workshop

- Related articles from the fantastic Tomorrow’s Professor series

- My favorite: Answers to Common Questions About the Teaching Portfolio; includes a list of questions to ask yourself:

- Is every claim made in the narrative supported by hard evidence in the appendices

- Is the portfolio sufficiently reflective? Does is include a balance of items from oneself, from others, and from student learning?

- Does the portfolio clearly identify what you teach, how you teach it, and why you teach it as you do?

- Is a complete table of contents and appendices included?

- Does the portfolio contain reflective observations?

- Have efforts at growth and improvement been cited?

- Are numerical student rating results included for several courses over several years?

- Have any department or institutional factors influenced your teaching effectiveness

- Would including some charts, tables, or graphs enhance the portfolio?

- Others, vaguely ordered by relevance: