In “If This is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories?,” J. Edward Chamberlin offers an enticing proposal when he touches on the metaphor of land ownership. Title, as Chamberlin describes it, is a legal fiction concerning a person’s right to do certain things in a certain area. In the comparative approach he emphasizes, this is one story among many, sacred to a certain “Us” as other stories are to other peoples. In Canada, there is a deeper player in the story of title: that of “underlying title,” belonging to the Crown.

The “Crown,” of course, is a poetic device, a kind of metonymy. It is a symbol for the reigning monarch, who in turn symbolizes the authority of Britain. Canada’s sovereignty, in ceremony at least, derives from it. A person’s ownership of a piece of Canadian land is a right granted by the federal government, but this right is devolved to it by the Queen of England.

Chamberlin suggests rewriting our national fiction. It is built, he says, on a contradiction between private ownership and “deeper” ownership. “Why not an aboriginal ‘trick’? ” he asks. “Why not change underlying title back to aboriginal title?”

This act could reframe the identity of the country, even if it had no effect on the day-to-day application of property law (Chamberlin himself imagines it wouldn’t). In contemporary battles on Aboriginal land claims, doctrine and precedent have maintained that the burden of proof is on the particular First Nation to justify their right to a valued place – i.e., to show how it belongs to them. To many such Nations, this is in itself an imposition. Writes Hanson (linked above), in pre-colonial times “humans, along with all other living beings, belonged to the land.”

This accords with Chamberlin’s further claim: that one factor in the failures of legal discourse in settling Aboriginal land claims has been the need to wrangle traditional stories into the ponderous language of legal storytelling. The language of Canadian law is founded on the thinkers of Europe. To the Europeans, to belong to the land symbolized serfdom, subjugation, wretchedness; to progress was to gain mastery of it. To some First Nations, the subjection of humans before nature (and, consequently, land) was a truth both elementary and sacred. These two conceptions of human beings’ relationship with the ground beneath their feet are not easily reconciled.

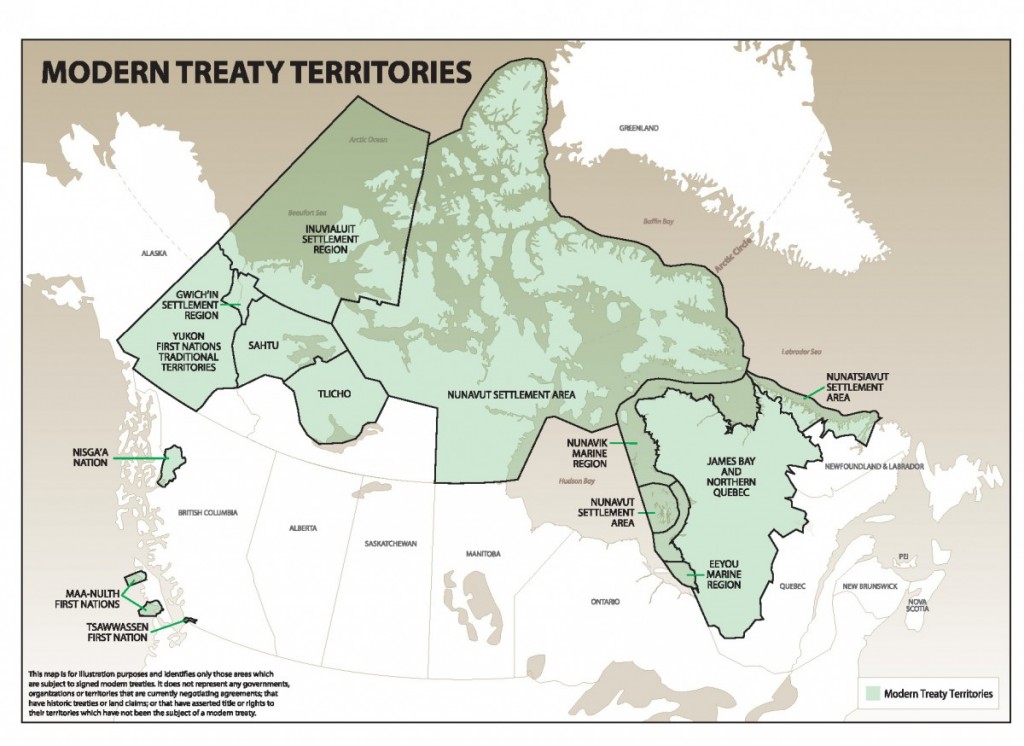

Perhaps Chamberlin’s proposal could supersede that conflict. Rather than making Aboriginal lands a scattered forbearance of the Crown’s omnipresent title over Canadian ground, Canadian roads and cities could become a scattered forbearance of a deeper right, held by the First Nations, to belong to the land that shaped, and shapes, their way of life. This could be achieved through a change in our country’s definition of underlying title that would also give it relevance in a world where the monarchy is increasingly thought of as an archaism.

What form would this take? Would there be a plurality of underlying titles, corresponding to each First Nation with their own particular claims, or a single one ratified by each? Or would the title belong to “the land itself,” on the understanding that this was an affirmation of the unique relationship the First Nations peoples have to it? This, I think, would be for them to propose.

Works Cited

Chamberlin, J. Edward. If This is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories? Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2004. Print.

Hanson, Erin. “Aboriginal Title.” indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca. University of British Columbia. n.d. Web. May 21, 2015.

“Commonwealth Members.” The Official Website of the British Monarchy. The Royal Household. n.d. Web. May 20, 2015.

“Implementation Issues.” Land Claims Agreements Coalition. Land Claims Agreements Coalition. n.d. Web. May 21, 2015.

Hi Mattias,

It’s very refreshing to read your post, focused on an actual practical change in the way we do things in Canada.

Last weekend at the breakfast table with my family, a conversation about royal babies led to the question of what would happen to all the royal property if the monarchy was abolished. We were talking about palaces and estates in England, initially, but we could ask the same question about most of the territory of Canada: Crown Land. It just shows, for me, how imaginary it is to claim all land as belonging to the Crown. Thanks for bringing up this point of Chamberlin’s, that underlying title in Canada should belong to Aboriginal peoples. Such a simple, clear, logical change!

I find it really interesting that Chamberlin is a professor of English and Comparative Literature who has been involved in so many land claim disputes. His career itself demonstrates a powerful connection between storytelling and legal issues. Other than the fact that he served as the Senior Research Associate with the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, I’ll have to look deeper to find out what it actually means that he “has worked extensively on native land claims around the world” (Penguin Random House Canada).

Thanks!

Kaitie

J. Edward Chamberlin. Penguin Random House Canada, n.d. Web. 24 May 2015. .

Hi Kaitie,

Thank you for thoughts. I found Chamberlin’s insights on law quite close to my heart. I’ve often felt that there is a touch of the magical to it, where people are set free or land transferred through the correct string of Legalese. In light of that, it’s quite unfortunate that the state has discounted the ceremonies of other cultures as “non-binding.”

🙂

Hi Matthias,

Your connection between different concepts of ownership – specifically the interpretation of belonging as serfdom is really astute. In my anthro class, I read a chapter last week discussing how the court process has required testimony of private and/or restricted knowledge to be made public, in order to prove land claims. In effect, our oral system still overrides the protocols and hereditary rights of Indigenous peoples, even in the effort to work for the positive resolution of land claims. Can’t end this one on much of a positive note, but certainly legal philosophy highlights so much about differing knowledge systems. For more on law, Bruce Miller’s work might be of interest – he studies the role of indigenous oral history as legal evidence, though he is not as flowery a writer as Chamberlin (for better or worse?).

Hi Heidi,

I didn’t know about that. Sounds like what I’ve heard elsewhere regarding land claims though. Thanks for the reference, I’ll have to investigate this Bruce Miller. 🙂

I quite enjoyed reading your blog entry! I was also really intrigued by Chamberlin’s suggestion of changing the underlying title, because it seems like such a natural and obvious step to take that I felt somewhat surprised that I hadn’t come across the idea before now.

I’d always thought of the Crown/Queen aspect of Canadian culture as being fairly meaningless, something that would’ve been removed by now if it weren’t for the fact that no one wanted to bother with going through the technicalities of doing so.

At the same time, it seems like giving Indigenous communities the underlying title would have a very significant effect on the way people see the land, in particular when it comes to our responsibility to take care of it and issues like when (or if) corporations are permitted to extract natural resources. I feel like this framing would affect my own perspective, even as someone who already knew about these issues. So this realization makes me suspect that perhaps the Crown’s role was never as meaningless as I believed – it was just that it had come to seem so natural that the effects were invisible.

I also liked your idea about giving the underlying title to the land itself, given that, as you noted, many Indigenous cultures see themselves as belonging to the land rather than the other way around.

Thanks Cecily! It was instructive for me too, to learn that these symbols that seem so remote can have a lot of significance.

🙂