In “Living By Stories” (2005), Wendy Wickwire partially relates a story told to her by the Okanagan storyteller Harry Robinson. At the creation of the world, two twins are sent to carry out some of the tasks: Coyote, the forefather of the Indians, and the first white man. In the course of his work, the white man steals a piece of paper he was not to touch. For this he is banished, but it is foretold that his descendants will return after many years to “reveal the contents of the written document” (Wickwire). But when they finally do return to the ancient birthplace, they start killing the descendants of Coyote and stealing their lands, all without keeping their promise to show the fated document.

I had a painful reaction to my first reading of the account – perhaps, because I saw it through the lens of the legacy in which I share. Colonization carries a motif of cultural genocide, coloured by shades of duplicity and insincerity. Robinson’s story is infused with this characterization of whites as treacherous and wanton. But the pain runs deeper than that, because Robinson also makes us kin.

John Lutz mentions that, in the late 1700s, “European intellectuals were engaged in a battle over whether man had been created in a single or a multiple genesis” (2007). Under either conclusion it was clear that, under European taxonomy, the Indigenous people of the Americas were to receive at most only reluctant admission into the human race. Today, of course, the scientific consensus has all H. sapiens descending from a common ancestor; but the first geographical split, it seems, could have happened 200,000 years ago or more – far beyond the edge of human collective memory. It has currency in our schools but not in our myths.

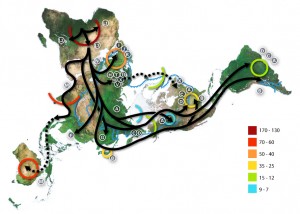

A favourite infographic of mine, representing a current theory of human migration – link

Creation stories cannot help but touch the core of one’s identity, be they of the body, the race, the world, or the universe itself. Hence, the pathos of Robinson’s “twinning.” By embedding the white man so deeply in his story of creation, he not only indicts them for their treachery but also brings them to the core of his spiritual world. From this many questions arise, of the kind that can only be answered through the play inherent in interpretation.

Does the kinship of twins in the story tell of a collision of cultures that extends into the spiritual world, of peoples that have become so enmeshed that their goals can no longer be pursued separately? What is the secret document? Is the paper symbolic of the power of the written word, coupled with the accusation that white culture has stolen and perverted it? Does the storyteller imply the possibility of reconciliation, or is he in favour only of resistance?

I’m reminded also of Franz Kafka, for instance his parable, Before the Law. An apparent theme, as also in The Trial and The Castle, is of the struggle to reach a faraway goal in some unknown direction, barred from sight by a dizzying labyrinth of bureaucratic redirection and shady passageways, but also accessible only through that labyrinth. This goal is sometimes symbolized by the Law, as in The Trial where the protagonist is trying to determine the nature of the charges laid against him. There seems to be an analogy with Robinson’s paper, and the Book of Black and White in the story where Coyote meets the king of England. This goal, this paper, would resolve everything, but it seems doomed to continually evade capture.

Lutz, John. “First Contact as a Spiritual Performance: Aboriginal — Non-Aboriginal Encounters on the North American West Coast.” Myth and Memory: Rethinking Stories of Indigenous-European Contact. Ed. Lutz. Vancouver: U of British Columbia P, 2007. 30-45. Print.

Kafka, Franz. “Before the Law.” (I. Johnston, trans.) Franz Kafka Online. kafka-online.info. n.d. web. June 11, 2015.

Robinson, Harry. (2005). Living by Stories: A Journey of Landscape and Memory. W. Wickwire (Ed.) Vancouver: Talonbooks.

Hi Mattias,

Great points about the significance of the Europeans and First Nations being siblings. I didn’t pick up on it during my first reading, but it seems like the story accomplishes the rhetorical opposite of what European contact stories try to – the latter makes the First Nations inferior “others” to justify colonial expansion, but Robinson’s story casts them as equals (if not superiors, being the elder twin) which makes it a violation.

Because you touched on it, I have to ask – what did you make of the paper that was stolen? The title to the land, perhaps, or rules for co-existence?

Hi Max,

I agree, and I think the way the story binds the two peoples together is what makes it so powerful. (There was once a different story, told by the Nation of Islam, saying that white people were originally created around 6,600 years ago by an evil scientist named Yakub who wanted to create a race of deceitful overlords – very much the opposite of Robinson’s vision!)

I could certainly imagine the paper being rules for peaceful co-existence, or a prophecy, or some other divine wisdom; but I see it above all as simply a symbol of literacy. Robinson says that the Indian keeps his knowledge in his heart and head while the white man keeps it on paper. To me, the story says that the written word was intended for all people but was stolen and used deceitfully by whites; and even when they arrived in the Americas and had the opportunity to offer it freely, they still withheld it. But the air of mystery surrounding that specific text is significant as well, and I think the freedom of interpretation it gives to the listener is part of the point.

🙂