The brain is a complex organ, and while researchers have made great strides in understanding its function and mechanisms, we still know relatively little about the consequences of damage to the delicate structure.

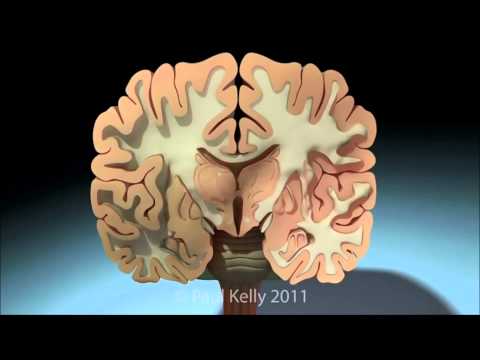

The brain is suspended in the skull cavity, and sharp accelerations can sometimes cause collisions between the unyielding bone of the skull and soft tissue, bruising the surface and damaging important neural connections within. This is known as a concussion, an injury common in contact sports where blows to the head are frequent.

A concussion can be harmful to anyone, but could the impact be greater on a developing brain, like that of a teenager’s?

Dr. Naznin Virji-Babul, a physical therapist and neuroscientist at the University of British Columbia, set out to discover the true extent of brain damage on concussed adolescents.

“The common perception of people is that your brain stops developing when you’re 3-5 years old. That’s not exactly true… the frontal areas of your brain are still developing when you’re a teenager,” she says, adding that this frontal area is what collides with the skull when a concussion occurs. The frontal and temporal lobes are most vulnerable to injury, and damage to these areas is associated with impairments of regular function. The study that her team conducted at UBC used Magnetic Resonance Imaging to gauge the extent of damage to the brain.

The study was conducted using a group of teen athletes, some of whom had experienced a sports-related concussion within the past two months and others who had not Each athlete underwent an MRI scan which measured the rates of diffusion of the fluids within the brain.

The results were surprising to the team, who had expected to find clear evidence of damage, and lower rates of diffusion in the concussed group compared to the uninjured group.

“But it was completely opposite to what we had expected, we thought we would find a decrease in [one of the tests] but we found an increase… It was like solving a puzzle trying to find out what was so different.”

Dr. Virji formulated a theory as to why the changes were different than expected: the neural damage in the brain was subtle, not outright breaking but causing smaller tears in the neuron which collect fluids and cause edema. This could throw off a diffusion tensor image but still indicates damage present in the brain long after the actual injury occurred.

“I wasn’t expecting to find changes in the kids who have had a concussion two months prior, but we still did… Kids and adolescents take longer to recover.”

These findings call to question the established guidelines concerning returning concussed athletes to play and school, as all of the concussed athletes scanned in the study had returned to their sport. Luckily, thanks to the findings of Dr. Virji and her team, new light is being shed on the nature of concussions on a teenager’s developing brain. This will hopefully lead to safer practices regarding the athletes care both during the game, and after.

This podcast covers further the nature of this resistance by the public towards concussions in adolescents, and how the established safety measures are not adequate enough to prevent brain injury.

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

For more information, feel free to watch this video on the impact of Dr. Virji’s research.

By: Ammar Vahanvaty, Derrick Lee and Ashley Dolman