“We’re doing it ourselves! We’re producing our own images”

An interesting way of looking at screen sovereignty is through the diverse and complex layers that conform its performance. In this blog, I will look at Kevin Lee Burton’s God’s Lake Narrows, which won the 2011 ImagineNATIVE award for Best New Media and compare it to Kristen Dowell’s ideas of screen sovereignty as argued in “Vancouver’s Aboriginal Media World” in Sovereign Sreens: Aboriginal Media on the Canadian West Coast. Imagine a piece of cloth whose fibers are woven thick enough for you to see each separate part conforming the whole. That’s how I think of screen sovereignty. Each layer of the process is important for the whole to become cohesive. Ideas of sovereignty, self-determination, acknowledgement, community building, self-production, circulation and audience are all key here.

Let’s begin then, with sovereignty. When talking about a governing body, we refer to it as sovereign when it has full right and power to govern itself without any interferences from outside sources. It means having independent authority. Out of this idea come two different concepts. Aboriginal sovereignty, which refers to the political status that ¨derives from Aboriginal peoples’ ties to lands prior to colonization”[1], and screen sovereignty, which is described by Dowell as the “articulation of Aboriginal peoples’ distinctive cultural traditions, political status, and collective identities through aesthetic and cinematic means”[2] but that we will start discussing in terms of self-determination.

Self-determination refers to the act to freely choose one’s sovereignty with no interference from outside bodies. Dowell, for example, argues that when Aboriginal people exercise an act of cultural autonomy by creating media work this is an example of self-determination. Specifically to cinema and visual sovereignty this involves the articulation of their “distinctive cultural traditions, political status, and collective identities through aesthetic and cinematic means”.[3] Creating content that reclaims decades of misrepresentation by the media is also an act of cultural autonomy because it takes advantage of the opportunity to assert control over how they represent themselves to each other and to non-Indigenous people. This particular point resonates a lot with the discussions surrounding the creation of the online gallery CyberPowWow in Jason Lewis and Skawennati Tricia Fragnito’s Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace, where they argue for the critical role that new media can play in shaping how Aboriginal people is seen by “Western, technologically oriented cultures”[4]. The camera, as they argue, taught people about Aboriginal people’s lives, rituals, belongings, and cultural practices. It taught people the grand amount of stereotypes that now reign over all PoC bodies. It controlled the language in which these stories were written, and by who they were written. Cyberspace, then, becomes a place full of possibility. A possibility we must question and be hesitant about, but a possibility nonetheless. As argued by Lewis and Skawennati, even looking at cyberspace from an economic perspective, its affordability is enticing. Production and distribution of mainstream media is extremely expensive, which is enormously reduced on the internet.[5] Messages through this medium can be propagated to a world-wide network of users. “We´re doing it ourselves; we´re producing our own images”.[6]

Dowell argues that although it is true that Aboriginal media has a certain aesthetic that is specific to their experience, there is no singular Aboriginal aesthetic. It is important that this point is made because that refuses a potential essentializing of Aboriginal media or “Fourth World Cinema” into this carefully labelled sub-category of cinema that could be used as a weapon of [further] erasure of Aboriginal stories in mainstream media. In terms of production, then, she argues that the off-screen process is crucial to understanding media production as an act of sovereignty because of the intensive labor that is involved in a filmmaking project: the production process is sovereign because it involves a community working together to create something. It moves through the ruptures achieved by the oppressive system in order to repair Aboriginal social relationships.

The [aboriginal]community involved in creating these projects is also very important, as visual sovereignty is also performed through the fact that content is produced by an aboriginal community, as previously argued, and for an aboriginal community. Although these films can and will circulate nationally and globally, they are made, first and foremost, with an Aboriginal audience in mind. Their messages are coded in such a way that some things will only be visible to the specific nation the creator belongs to or to the Aboriginal people at large, which isn’t to say that non-Aboriginal viewers are not able to engage deeply with Aboriginal media, but it means that some content will resonate particularly and personally to an Indigenous audience.

The circulation of these films, in the larger movie or media industries, ultimately becomes part of the larger archive of film and media, which becomes an acknowledgement of existence and presence by the fact that non-indigenous people are watching. it is using the language of the hegemonic system to work from within. Speaking the language of the medium in order to politically, materially, and tangibly take up space in the discourse, which subverts unequal power dynamics[7] to claim a right for self-representation. As Dowell rightfully says, “for some filmmakers the mere presence of Aboriginal faces and voices on screen is itself a revolutionary act of self-determination”.

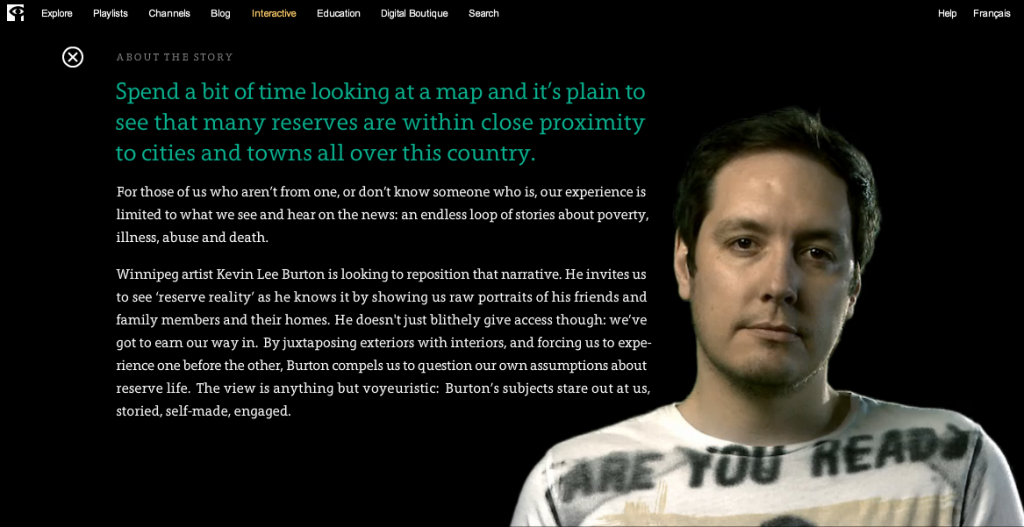

Let’s talk about Kevin Lee Burton’s God’s Lake Narrows. Although I have discussed this piece in my Indigenous New Media class, I wanted to describe the experience and analysis of this piece from my [very ignorant] perspective. To position myself, and as I have mentioned before, I am originally from Mexico, Mexico City to be precise. This is a city reigned by the most beautiful, bubbling, alive and messy chaos I have ever experienced. I lived in this city for my entire [conscious] life before moving to Canada for university. Nevertheless, I would never say I know Mexico City. I think one never gets to fully know Mexico City. With more than 25 million people and its big city quality there is not one recognizable “aesthetic”. Being the place where hundreds of indigenous, colonial, mestizo and contemporary histories collide and mix in a weirdly syncretic harmony, feelings of sameness and similarity are complex. Where I come from, snow is nothing but a distant idea portrayed in movies about Christmas. Where I come from, people mostly live in apartment buildings, because it is either too densely populated to have houses or it is too expensive. We never play bingo. In fact, we only know bingo from movies that portray it as a game played mostly by really old people. We eat pizza though.

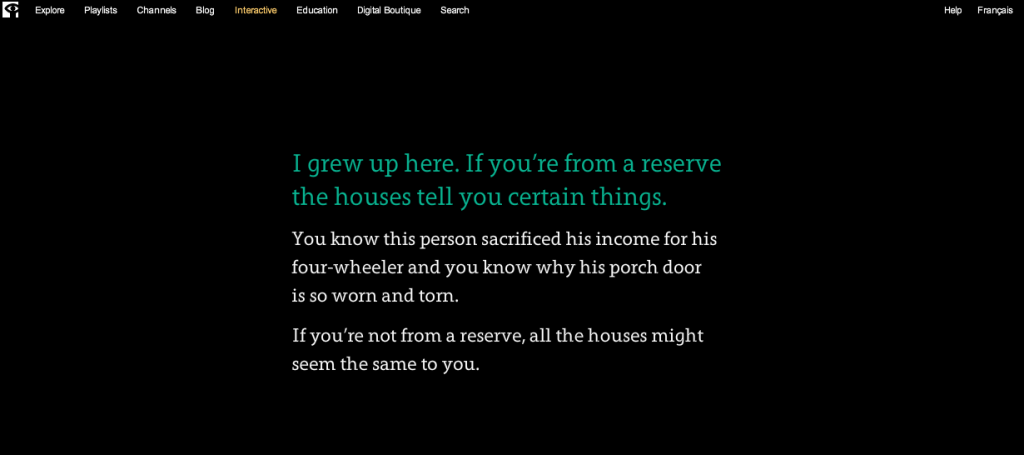

I say all this because my experience of God’s Lake Narrows had to be translated or decodified to me by my classmates and peers who grew up to similar experiences than the ones portrayed in this piece. I begin this immersive experience with a sound installation that combines a juxtaposition of sounds that make me aware that I am entering this space as a guest. I do not know what most of these sounds represent. I know, by the characteristic sound of a radio that tunes in, that I am listening to a recording of a communication device probably used in reserves. I hear the sound of a shovel doing something. I am later told that this is a shovel, moving snow around. Perhaps people ice skating, I am not sure. I see a map of Canada, lighting up, as the piece loads. I then see text, written by Kevin Lee Burton in the first person, telling me how far I am (in Vancouver) from God’s Lake. He knows where I am. He also seems to know that I have never visited a reserve before, because I am not Indian [from Canada, might I add]. I am now presented with several options, but I click on the “forward” arrow, as that seems to be the easiest way to continue. I am already aware that this piece is exercising screen sovereignty by the way in which I am marked as guest from the moment I start engaging with it. This content has been produced by an indigenous community, led by Burton who grew up in God’s Lake, and primarily for an indigenous audience. First of all, it will specially resonate as home to those who, like Burton, grew up or still live in God’s Lake, as they hear the sounds from their community and see the landscape that they encounter every day. Secondly, it will resonate with those who grew up in other reserves, as, in his own words, there is a certain aesthetic to these houses that is similar throughout the country. Nevertheless, this is not to say that he is not addressing those like me, who have no experience living in a place like this, as he makes a point of letting us know that we probably would not recognize most of the cues he is making visible here, asserting one more time, the insiders, the hosts, the owners, and the outsiders, the guests.

As I keep moving through the digital space, I am introduced to the façades of six houses, all halted with the black screen with white and turquoise text, in which Burton introduces statistics about the amount that has been spent in order to build this “reserve aesthetic” with childhood memories that highlight the fact that a lot of basic needs were denied to his community for most of his childhood. He also introduces a lot of dichotomies, from longing and (be)longing to proximity versus invisibility. Although the closest reserve in Vancouver is 1.9 km away, out experience is dictated by what mainstream media portrays about them and their lives as well as living conditions. Thus, he is constantly challenging those stereotypes by showing us what some of the houses in his reserve look like and by sharing what the interior of those spaces is like in reality.

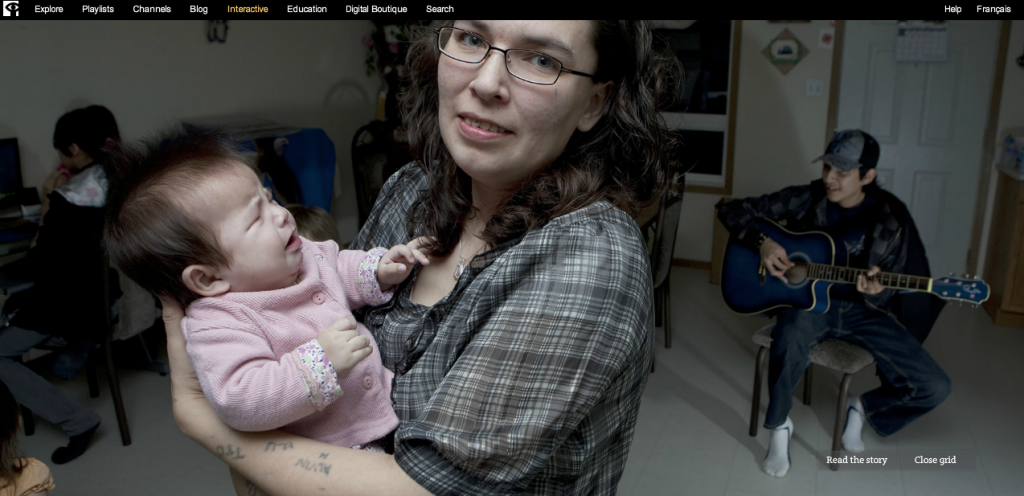

Ultimately, this experience is the epitome of self-determination. God’s Lake Narrows engages with the stereotypes that exist about his community, as well as Indigenous communities in Canada at large, and he reclaims the misrepresentations to portray the reality. The duality within the beautiful landscape but the underlining tones of ignorance, forced dislocation, poverty, etc. It is using one of the most technologically advanced languages to create an interactive experience in which the viewer has to engage critically with the gaze of the Indigenous peoples’ whose photographs we see, gazing right back at us, challenging our assumptions, folded arms in front of us.

It also engages with the ideas of off-screen production and labor mentioned before in which sovereignty is portrayed by a community that works together to create something. It moves through the ruptures achieved by the oppressive system in order to repair Aboriginal social relationships as we see several generations portrayed in an experience that becomes a social process in which networks of Indigenous people are reinforced.

Lastly, this piece masterfully decolonizes two of the most important ways in which the institution of art and art history colonize the Other: the gaze, mentioned above, and the grid. The gaze is subverted by the photographs that showcase people in their homes, looking back at the camera, at us, giving us permission to look into their homes and see their families. The grid, which has been marked as the most important feature of [western] modernism, as Rosalind Krauss historicizes:

“in the early part of this century, there began to appear, first in France and then in Russia and in Holland, a structure that has remained emblematic of the modernist ambition within the visual arts ever since. Surfacing in pre-War cubist painting and subsequently becoming ever more stringent and manifest, the grid announces, among other things, modern art’s will to silence, its hostility to literature, to narrative, to discourse.”[8]

The appearance of the grid marked the break from representational painting into minimalism and abstract art. What this history fails to acknowledge is the existence of grids previous to this Western modernity, seen in universally known but surprisingly unacknowledged textiles, who have been using grids and other complex mathematical systems as guides for the visual and representational histories of entire communities. In this way, Burton presents his work in a grid that is both a rational system and a representational one. It is not a break, but continuity. It marks and delineates a sovereign portrayal of a community that invites you to earn their respect. That provides you with a set of ideas and knowledge that you know will now carry with you. I would like to end this post in Burton’s own words:

“It is imperative that we keep focused on who we are and what we wish for ourselves, the old ones and our children – and keep on that, as consistently and adamantly as we can. Our parents and grandparents endured so much in a short span of time, that it is baffling how they remain such coherent and loving people – now it is our turn to take on the role of working toward sustaining our cultures, languages and identities. Our realities were abstracted for some time, but now we must carry forward, translate and re-translate the visions of our people, a sort of ‘booya-kah! booya-kah!’ to Colonization.

We are still here and that is worth appreciating.”

[1] Dowell, Kristen. “Vancouver’s Aboriginal Media World” in Sovereign Sreens: Aboriginal Media on the Canadian West Coast, University of Nebraska Press, 1.

[2] Dowell, Vancouver’s Aboriginal Media World, 2.

[3] Dowell, Vancouver’s Aboriginal Media World, 2.

[4] Lewis, Jason and Skawennati Tricia Fragnito, “Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace” in Cultural Survival, 29.2, 2005.

[5] Lewis, Jason and Skawennati Tricia Fragnito, “Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace”

[6] Cleo Reece in Dowell, Vancouver’s Aboriginal Media World, 2.

[7] Dowell, Vancouver’s Aboriginal Media World, 5.

[8] Krauss, Rosalind, “Grids”, October 9 (1979): 50.

Thoughtful and interesting piece, Valentina! From the beginning I was intrigued by your allusions to textiles, imagining screen sovereignty as a pieces of cloth with interconnected fibers. Similarly your writing on the grid and textiles was very thought-provoking. Your analysis of Dowell’s writing and Gods Lake Narrows was clear and easy to follow. And the paragraph on Mexico City and your position as a outsider to Gods Lake Narrows was very strong.

You described Cyberspace as “a place full of possibility. A possibility we must question and be hesitant about, but a possibility nonetheless.” How do you think Kevin Burke questions or negotiates the possibilities of cyberspace with Gods Lake Narrows? Does he show any hesitancy?

I really like the close reading of GLN you do here, Valentina–particularly via Krauss’ notion of the grid. Fascinating stuff. It made me think about Western conceits of “vanishing points” and the Cartesian Plane. I think you could dig into that analysis even further if you chose.

I also appreciate the self-positioning you offer for your reader here. I think that part of what makes Burton’s piece so interesting is that he made it to give more people access to what is a mostly inaccessible community. As such, we need to think about the vast number of ways in which the work is received and interpreted. You set an excellent model for the ways in which folks can position themselves in relation to the work.

Hi Valentina! Among many things in this post, I really appreciate your discussion of God’s Lake Narrows as it relates to screen sovereignty in the medium and the message – both of which clearly demonstrate sovereignty in different ways. I also like that you drew on more personal experiences and situated yourself within this piece. I think that self-reflection in that way is actually a main piece of what Burton intended to inspire with his website. I also really like that idea of “gaze” and “grid” that you brought in at the end to further complicate God’s Lake Narrows.