Back in February I had the immense pleasure and honour of witnessing the third annual Grand Mamas event. Grand Mamas is a space where Indigenous, Black, and racialized artists and activists share poems, stories, and songs (and sometimes a combination of the three) about the women in their lives—mothers, grandmothers, aunties, cousins, sisters, daughters, and chosen family to name but a few.

It was curated three years ago by three incredible queer femme organizers Amber Dawn, Anoushka Ratnarajah, and Jen Sung.

All the proceeds of the night go to the Downtown East Side Women’s Centre’s program “Warriors Organizing Women”, to help them in their organizing of the Annual Memorial March for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women every Valentine’s Day.

So, right off the back, I think its important for me to recognize that Grand Mams is not only a space of challenging heteropatriarchy and misogyny, but it is also held in service of an anti-colonial resistance that it is already happening, and has been happening for the past 26 years.

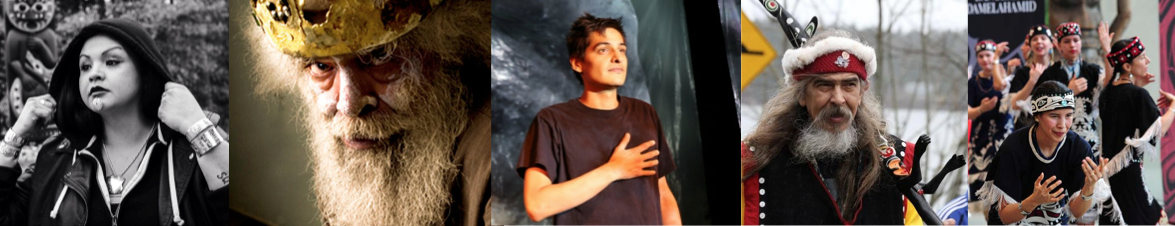

The Indigenous performers of the night included:

Squamish, Stó:lō, and Hawaiian mother-daughter duo Cease and Senaqwila Wyss, who conducted a land acknowledgement and sang a “Winter Bird” song to welcome the Elders and the women in the room.

Queer Gitxan/Tsimshian photographer and artist Jessica Wood;

and Cree Métis writer Samantha Nock; who (along with Jessica Wood) read original writings.

The immense love that undersocored the night can be seen in one of the poems that Nock wrote, called “pahkwêsikan’ ”, or “Bread”, which honours her Aunty and her method of cooking fry-bread as an act of self-love immediately following a breakup with a boy who left her for a white woman—and the immense insecurities and internalized racism that this breakup triggered.

I won’t say too much more because I focused on this piece for my paper, but I will talk about honouring and giving thanks—which for many Indigenous artists, is a central component to their work and life.

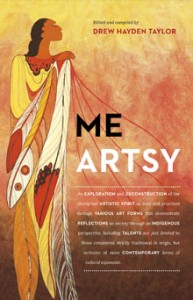

As Mohawk scholar Santee Smith, in her chapter “Dancing Path” from Me Artsy, says, ““Whether directly inside of a work in song or spoken word, thanksgiving is the leaping-off point.” (2015, 113)

For Smith, giving thanks has become, and I quote, “a fundamental aspect of [her] individual and artistic aspect” (113).

Giving thanks through art, she continues, orients one to be mindful not only of their relationships to other beings, but also to their connection with the spirit world. It orients one to ask:

What is the status of our humanity and our relationship with the universe today? How well are we faring as custodians of the earth, the plants, the medicines, the four-legged ones and the elements? What of the water and fish, how are they faring in our humanity? (2015, 112)

This interconnectedness through giving thanks, I think, could be seen throughout the event.

The event curated by three non-Indigenous organizers, but they gave focus and space, as well as amplified, Indigenous voices and stories.

The artists were sharing poems and songs in thanks of women in their families, whether chosen or by blood. These exchanges were intergenerational—one of the artists (they weren’t Indigenous) read a poem about their mother to their mother, who was sitting in the front row of the audience.

Again the event ultimately was to support the March honouring the lives of the missing murdered Indigenous women in the DTES, a profound expression of love, and honouring, and giving thanks.

As well, at the end of the event, Elders lead a singing of the women’s warrior song with everyone in a circle holding hands—in this to me symbolized ethical allyship—wherein settler-colonialism is acknowledged as a serious issue that needs to be addressed, and we’re coming together to further dismantle it, while the voices of Indigenous Elders and leaders are amplified and not appropriated.

As Monique Mojica explains in “Verbing Arts”, also from Me Artsy:

“Art is defence.” I art in defence of women’s bodies. “Art is action.” I art to make our knowledge speak.

I art to for that little brown girl asking, “Why war?”

Over and over again…

I art to protect our lands, waterways and breath.

I art for all the young Indigenous artists coming up fast behind me who don’t know a world without Indigenous artists in it.

…I art for you.” (28)

And so Grand Mamas, as I witnessed it, was a site of thanksgiving, connection, defence, action, and alliance-building when seen through the various lenses of Indigenous performance.

Discussion questions:

- How may Grand Mamas offer a glimpse into Karyn Recollet’s concept of “radical decolonial love”?

- How do you feel about the title “Grand Mamas”? Does it take away validity from women who are assuming different roles (familial or otherwise) in their communities?