Panel Discussion for Dana Claxton’s exhibition Made to Be Ready February 27, 2016 / SFU Audain Gallery

As part of the public programming for Dana Claxton’s exhibition Made to Be Ready, a panel discussion was held that featured three speakers in the location of the actual exhibition space. It was neat in this circumstance to be surrounded by Dana’s work while conversing about it. It was a full house with a mixed audience of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, curators, artists, MFA students, and local scholars in the Vancouver contemporary art scene. I recognized a majority of people from my involvement in contemporary art, most of whom I haven’t previously seen at other Indigenous related events we’ve been going to as part of our course.

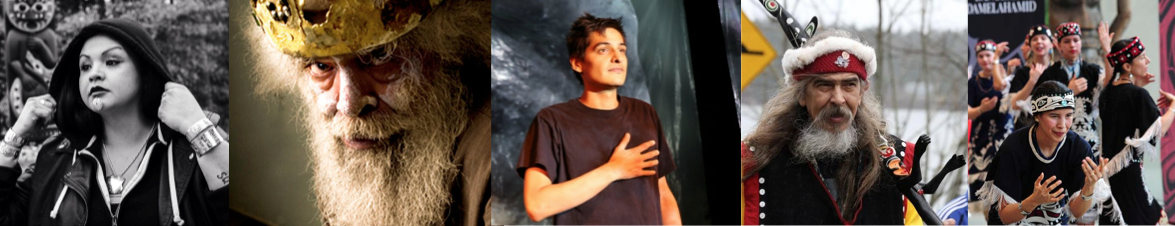

The speakers were:

Monika Kin Gagnon, a Professor of Communication Studies at Concordia University who “has published widely on cultural politics, the visual and media arts since the 1980s.”

Richard William Hill, a curator, critic and art historian and is a Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Studies at Emily Carr University of Art and Design. “His research focuses primarily, but not exclusively, on historical and contemporary art created by Indigenous North American artists. As a curator at the Art Gallery of Ontario, he oversaw the museum’s first substantial effort to include Indigenous North American art and ideas in permanent collection galleries. His essays on art have appeared internationally in numerous books, exhibition catalogues and periodicals.”

Tania Willard, who is of Secwepemc Nation and is a curator who “works with the shifting ideas of contemporary and traditional as they relate to cultural arts and production, often working with bodies of knowledge and skills that are conceptually linked to her interest in intersections between Aboriginal and other cultures.” Her curatorial projects have included Beat Nation: Art Hip Hop and Aboriginal Culture and BUSH gallery, a conceptual space for land based art and action led by Indigenous artists.

The Moderator:

Catherine Soussloff, a Professor of Art History at UBC, in which I had the pleasure of taking her course on Performance in Art History (Fall 2015). “She is known for her comparative and historical approaches to the central theoretical concerns of European and North American art and aesthetics, including photography and film, from the Renaissance to the present.”

Opening:

Melanie O’Brian, the Director of the SFU Galleries, opened with an acknowledgement of the panel taking place on unceded Coast Salish territories. Amy Kazymerchyk, the curator, presented some of her questions and approaches she has been considering in her curatorial practice, one of them being: “How can contemporary art fit with Indigenous practices as acts of doing, becoming, and worldmaking that emphasizes the liveliness of presence?”

My overall experience of witnessing:

I felt like I went in to the panel with two ways of seeing, that is through the knowledge I have gained through my experiences of being in the contemporary art scene, and the knowledge I have gained from Dr. Dangeli and our class discussions. As a result, I was able to apply these two ways of thinking to realize that the discussion overall was both productive and lacking in the elaboration of certain points made.

Overall, I found that there were many contrasts between the panel discussion and the way we had approached discussing this exhibition in class. The panel focused more on the theoretical side of applying certain theories and notions to Dana’s work instead of also reflecting on how we may be personally witnessing Dana’s work through our own individual ways of responding in relation to the backgrounds we come from. The majority of the audience was reluctant on expressing the specific meanings and kinds of narratives occurring one may individually draw from the works. Instead, the panel centered around how Dana provides an alternate framework for challenging dominant ways of seeing in the space of a gallery and inverting narratives, which brought out many important points, but also felt lacking. I found that there was little commentary or elaboration on specific cultural belongings and their ceremonial and sacred relations (especially compared to our class discussion), and most of the time, the works were not addressed by their actual titles, and only through their mediums and physical locations. The speakers mostly addressed Uplifting in all of their presentations.

Key topics & terms addressed:

Monika’s Presentation: Monika talked about her personal experiences she has had with Dana in the 90s, a time when Dana began to strongly influence the starting up of creating space for Indigenous works and performances in Vancouver through the Pit Gallery.

Vocalization: Where complex narrative structures in which multiple perspectives can arise as being unstable and unfixed. Monika stated that the narrative in Uplifting pulls us through to this direction, and that Dana brings a strong positionality that we’re not used to seeing dominantly, in which she uses vocalization as a strategy.

Richard’s Presentation: Richard spoke about associations of Claxton’s work as being inconclusive and indefinite.

Bodies of Matter: As in Uplifting, he stated that the body is both bound and spiritually transcended, oscillating between the two. He described the video as taking on a poetic expression of song and dance, moved by the pace of abstraction. With the video having a quick loop, he asked if the woman in it at the end has either transcended or fallen, has overcame struggle or not, stating that the way of tradition can be both a blessing and a burden.

Audience response: In response to this, an artist I recognized (who is based in Vancouver of Chinese origin), spoke up to say that there’s also many other layers in between the video to consider in relation to how it ends, in which she stated that the end is not affirmative and we should consider the in-between acts of what happens (this made me think of Recollet’s discussion on ‘in between’ spaces). This audience member also stated that she is not to speak to specific Indigenous content coming from her own background, so she does not go into further elaboration on what these in between spaces could mean to her, even though it was nice to hear her point out that there’s something more happening in the video than just whatever the ‘outcome’ of it might be.

Location of art & art made for location: Richard states that Dana plays with tensions of the gallery space, questioning what it can be and what it has been. He asserts that landscape is present in gallery’s space through the horizontal axis of film, which allows for it to be a space of speculation on a connection point that is between the earth and sky.

Tania’s presentation: Tania spoke about Uplifting in relation to Indigenous women and principles of living in beauty. She emphasized the insertion of Dana’s generosity in the exhibition space, which is filled with provocation and beauty. She has previously worked with Dana on curatorial projects before.

Intuitive navigation: Tania states that Dana helps us to arrive at an intuitive way of navigating relations between culture and institutions, but also denies us. As we consume her work, her work consumes us: it has obstacles that interrupts how we usually consume materials and beauty.

Internal ways of seeing: In reference to this, she also states that Dana makes us rely on internal ways of seeing through her cultural belongings, as they carry things that which we remember ourselves and our families in.

Space of slowness: Another point Tania makes is how Dana gives us gift of time, stating we’re gifted to be here and exist with its recorded performance for a period of time, to understand it as a ‘tool of way finding’. She discusses how Dana offers us spaces in-between that we start to fill ourselves with and read into these subtleties so that we can begin to see other paths and avenues that are filled with dignity and potential. But again, I found that these possibilities of ‘potential’ are not elaborated on in terms of how we can take action of our responsibilities as witnesses.

Side note: At this moment when talking about space of slowness and reflection, a little girl sitting in front of me who was playing a video game during the discussion looked up for the first time and took a moment to pause and watch the crawling woman in the video. It was a neat moment to see this happen at this time when we were all silent and really giving our attention to the struggling pain the woman was undergoing in the video.

Catherine’s discussion: Catherine began by introducing herself as an outsider (has been living for 6 years in Vancouver), and describes Dana, her colleague, as an art warrior for her people, being on the inside (of her Lakota culture) while operating on the outside (the art world). She states that Dana is made to be ready to teach meanings and ways of knowing the world from both sides.

Towards the end, she asked us how do we find the right kind of language to use that justifies this work? She stated that to her, the theoretical is the right kind of language for herself to use as an outsider.

Strategies of indirection: Catherine referenced Gerald Vizenor’s notion of ‘indirection’, of which she stated that Dana uses the gallery space indirectly by having an active presence asserted in it, but without having a live performance happening. The idea behind having this indirection is to mean that there is no direct way of knowing.

Reading Relation: Monique Mojica, “Verbing Art” (Me Artsy)

“Indigenous cultures recognize the need for performance and repetition.” (17)

In addition to Dana’s intentions to disrupt ways of seeing in the gallery space and inverting standard narratives, I feel that she is also reminding us or making aware, especially to an audience who who may be unfamiliar with, of how much performance and repetition has always been and still has a profound presence at the core of Indigenous cultural practices. I think this point Mojica makes could have contributed nicely in thinking about performance in the panel discussion.

Mojica’s notion of ‘auto-biological’: the performances Mojica creates “lives organically in her body”, “as a continuum of embodied stories“ (from her immediate elder generations, her ancestors, and from ancestral land) is what “connects her to the temporal space of performance”, which then “evaporates, held in memory until it is repeated”. (17)

Without having the temporality of a live performance, I think that this idea of the ‘auto-biological’ can be lost a bit through the mediated representation of the woman’s movement in Uplifting, but the idea of repetition is emphasized to remind us of ancestral continuation. Perhaps one of the reasons that this discussion may have lacked consideration of a personal way of responding and internal witnessing of the exhibition is because it exists as a space of performativity without having the temporal experience of moving bodies performed live.

I thought this quote (below) from Mojica’s piece of writing is a nice way to end this post off with. I feel it reflects the other way of seeing I have come to experience through our Indigenous performance course that could help to bridge the discussions that took place in the panel and our thinking about how we each can relate to the living force in the exhibition space that Dana generously presents us with:

“Living as an artist has required me to be fearless in search of cultural recovery and to reclaim those missing pieces with fierceness in order to put unspoken language in my mouth and unpracticed rhythms in my feet, to literally put myself back together.” (16)

Thanks for reading on, see more on our presentation slides!

https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1bMtaRdWRwUP-_Upk1oWMy2JTsydszCTF4EGNJ_4fn20/edit?usp=sharing