5] In her article, “Green Grass, Running Water: Theorizing the World of the Novel,” Blanca Chester observes that “the conversation that King sets up between oral creation story, biblical story, literary story, and historical story resembles the dialogues that Robinson sets up in his storytelling performances (47). She writes:

Robinson’s literary influence on King was, as King himself says, “inspirational.” When one reads King’s earlier novel, Medicine River, and compares it with Green Grass, Running Water, Robinson’s impact is obvious. Changes in the style of the dialogue, including the way King’s narrator seems to address readers and characters directly (using the first person), in the way traditional characters and stories from Native cultures (particularly Coyote) are adapted, and especially in the way that each of the distinct narrative strands in the novel contains and interconnects with every other, reflect Robinson’s storied impact. (46)

For this blog assignment I would like you to make some comparisons between Harry Robson’s writing style in “Coyote Makes a Deal with the King Of England” and King’s style in Green Grass, Running Water. What similarities can you find between the two story-telling voices? Coyote and God are present in both texts, how do they compare in character and voice across the stories?

In Green Grass, Running Water, author Thomas King allows for the segments in the novel between the four old indian women (and coyote) to feel dialogic and have elements that seem inherent to speech and not necessarily to writing.

Where did all the water come from? says that GOD.

“I’ll bet you’d like a little dry land,” says Coyote.

What happened to my earth without form? says that GOD.

“I know I sure would,” says Coyote. (GGRW 38)

The dialogue where Coyote isn’t either apologizing or asking questions, usually promotes Coyote to be of a single track – overlapping and responding to his own speech and less reactive to that of the other characters. This is a characteristic that is often associative of speech and not of narration in a novel. In this passage, Coyote also seems to have knowledge before and beyond the characterized “GOD”, perhaps associating this God characterization to knowledge that isn’t connected to the stories being told by the old Indian women. This puts Coyote into a position of knowledge beyond that of western omnipotence. It is no surprise that shortly after in the story god has a new adjective, “that backwards GOD” (GGRW 39). God’s intentions or stories are directly in contrast with those of the four women.

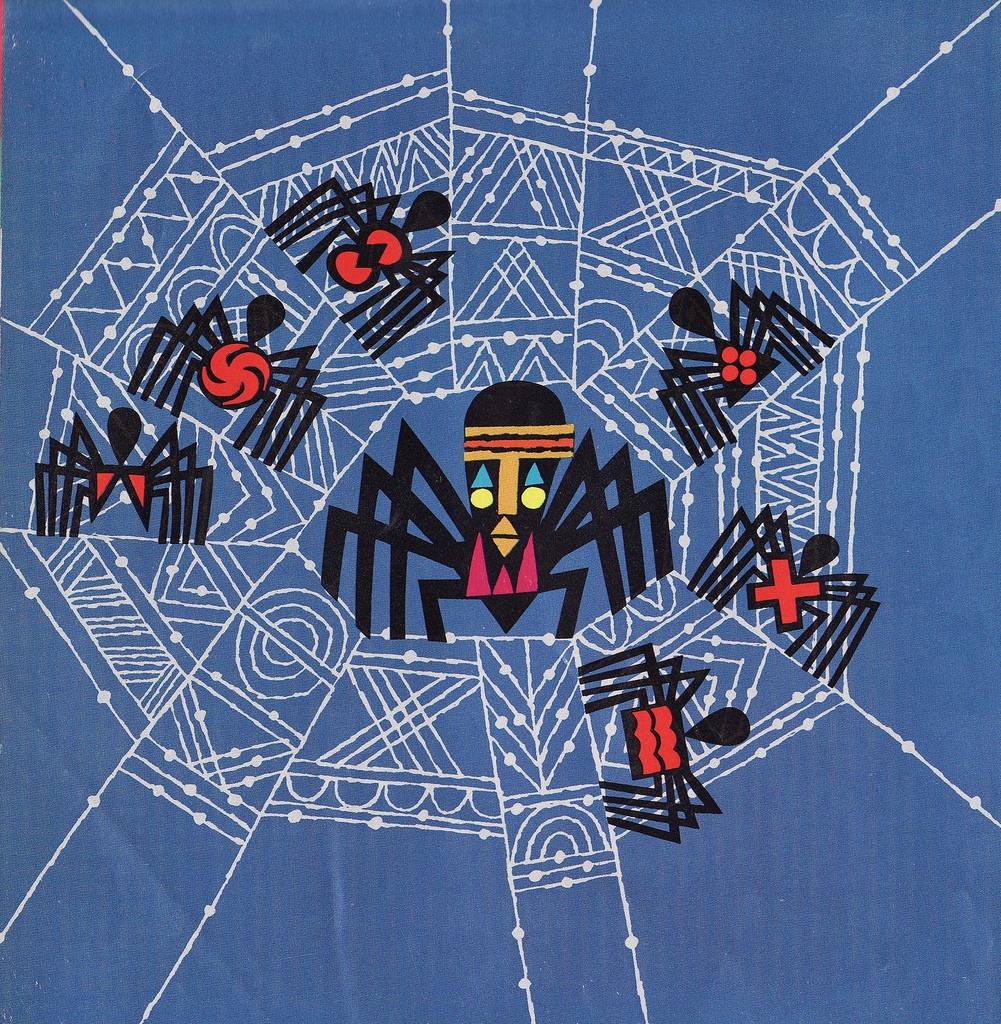

Certainly, for me coming into contact with this story after reading Harry Robinson’s, Living By Stories, the character of Coyote had more authority than usually associated to a trickster character. One of my first interactions with the trickster was through the stories of Anansi the Spider. Often Anansi would fall into trouble and have to be saved by one of his sons (all that had a specific talent to help their father with. In these tales, although intelligent, the trickster often was in need of rescuing or alternatively, got others into terrible trouble while dodging their own confinement through intellect.

The Coyote depicted by both Robinson and King seems to represent something greater, for King certainly, Coyote needs to be guided much more than necessary. Through this King reasserts the interruptive dialogic feel into his narrative. Although Robinson does not have this same style of interruptive text, the pacing is similar in his text as it is in the segments of King’s book dedicated to the old Indian women. King often uses dialogic interjections like “oh, oh” (GGRW 39) or the narrative “you know” (GGRW 38) or “you get the idea” (GGRW 269) at the end of sentences. These kind of dialogic elements to the writing really help it become something that feels spoken as opposed to simply words on the page. The words spoken by Coyote and the old women are vocalized in my brain, where the more through-line story exists outside of me, on the page.

Robinson reflects similar vocalized patterns in Living by Stories, the slang like, “and was just forced, like.” (LBS 75); this in addition to replicating an oral grammar gives the whole story the sound of someone’s speech as opposed to a cut and dry narrator. Robinson also retains the “you know” (LBS 77) intermediary interjection and a very verbal pattern of “so, because” (LBS 76) to start a sentence. All of these speech replications tie the language of Harry Robinson to a similar speech used by King’s old women. Although Coyote and God are very differently reflected, they really have a similar feeling because of the language used to describe them.

Works Cited

“Anansi the Spider (1972).” Picture Books Review. Blogger, 16 Jan. 2013. Web. 1 Aug. 2015. <URL>.

King, Thomas. Green Grass, Running Water. Toronto: HarperCollins P, 1993. Print.

Robinson, Harry. Living By Stories: A Journey of Landscape and Memory. Ed. Wendy Wickwire. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2005. Print.