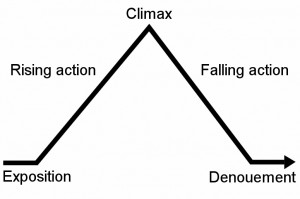

In 1863 Gustav Freytag published Die Technik des Dramas, a book in which he considers dramatic structure in ancient Greek and Shakespearean tragedy. Freytag’s model of dramatic structure has been appropriated for use in teaching the short story, but whether it is suitable for this purpose is debatable.

Considering the four short stories assigned for this week, to what extent is Freytag’s Pyramid useful when applied to contemporary fiction? What other approaches might be employed in considering narrative structure?

I would like to comment on the appropriateness of Freytag’s model. I think it is appropriate to teach this model in the broader context of literature as whole. The diagram is useful as a jumping off point. It would be easy, for example, to plot any Hollywood movie against this diagram. It is easy then to demonstrate the ubiquitous nature of this form and then to show students examples, like ‘The Tell Tale Heart” where it doesn’t work. The key is not to teach it as an absolute but a way to plot a story graphically. I do think that this model is most useful in looking at drama, and then once students are comfortable with it asking them if it applies to any of the short stories they have read.

It is important to remember that some students are visual learners and this kind of exercise is one way to reach them. They just have to realize that the line can take any shape and that there are no right or wrong answers.

It seems to me that Freytag’s model is, as Fred states above, best served as a rudimentary concept from which to explore interpretive possibility. To my mind, the danger with routinely insisting on this model per se, is that it fundamentally endorses ‘action-driven’ plot recognition, thereby endorsing ‘events’ over ‘language.’ This focus may possibly encourage adolescences to simply plot-out Munro’s ‘Boys and Girls,’ for example, by routinely applying the Narrative Structure Model, and by doing so, simply tagging spikes in action with memorized literary terms. Approaching literature this way, I think, fails to respect the students imagination, and perhaps, even ultimately fails the literature itself. I’d think, rather, that simple ‘action-based’ discussions can instead become pretexts for investigations into ‘language-based’ comprehension, and the freedom to which the student’s answers can vary hopefully shows them that this freedom needs only to be evidenced to strengthen their argument in context. As long as they learn to support their findings, then that seems more important than mapping out, say, the slaughter of Mack or the freeing of Flora. To exemplify this, I feel that there are a few philosophical passages that more or less lend essence to the actions that seem obviously important at first glance. For example, I’d suggest that gender is used to allegorically convey higher concepts of rebellion and hope. Reading through this story, I couldn’t help but read it through Shelley’s poem Mask of Anarchy. By listening to the language, actions implicate further actions as practices of revelations in philosophy: the girl’s thought transforms from previously unquestioned obedience to figurative actions of transgression. The girl’s action of stalling at the gate can be partially traced to her philosophical divergence from authority, seen in her father:

“ . . . we were used to seeing the death of animals as a necessity by which we lived. Yet, I felt ashamed, and there was a new wariness, a sense of holding off, in my attitude to my father and his work.”

This insight leads to a later realization of the assimilation that awaits both her inscription into gender, and more strikingly, into violence and obedience, as well as the slaughter that awaits Flora. The hesitation that results in the freedom of Flora represents a bid for hope, a hope against the inevitability of gender-slavery and senseless death, again paralleling Shelley in its rebelliousness:

“ I no longer felt safe. It seemed to me Innocent and unburdened like the word child; now it appeared it was no such thing. A girl was not, as I had supposed, simply what I was, it was what I had to become.”

The girl’s realization of the gender that is to consume her speaks of higher concepts of discipline, order, and subservience in Shelley. What it interesting is that in Mask of Anarchy, Anarchy comes riding on a horse splashed with blood wearing a “kingly crown / and in his grasp a sceptre shone / On his brow . . . ‘I am God, and King, and Law.’” However, before Anarchy can completely trample the ‘adoring multitude,’ (I’d go as far to say that the horse meat-foxes-living cycle could represent obedience-ideology-power) a maid named Hope ‘lay down in the street / right before the horses’ feet / Expecting with a patient eye / Murder, Fraud, and Anarchy.” What speaks so strongly of these themes to me is that the girl in Munro dreams of stories of ‘courage, boldness, and (most notably), self sacrifice.’ In her dreams, she also rides a ‘horse of heroism’ and fends off wolves from teachers that cower behind her; she sees herself as the source of revolution, even once falling off a horse to have it ‘step placidly over’ her as does Hope in Shelley. The girl’s Father and her brother Laird are frequently described donning aprons splashed with blood, (as is Anarchy) seemingly linking masculinity/authority to bringers-of-violence, or as in Shelley, ‘ God, King and Law.’ The story also opens with images of England and France. The Peterloo Massacre as depicted in Shelley is set in the former, premised on fear of becoming the latter, as experienced during the French revolution.

Whatever the interpretation, I shared to open the possibility of students being able to learn how to link themes in literature with other themes in other works. This can be shown using companion pieces, or at least, related/contrasting poems, stories, songs, movies, and so forth. Perhaps what can be taken from Freytag’s model is that it can be less of an indicator of absolute plot, and more a trajectory of philosophical proportions behind the actions themselves, as a way to strengthen the ability to detect larger themes, while empowering their imagination to feel around behind the plot unfolding.

Mask of Anarchy: http://www.infoplease.com/t/lit/shelley/1/12/1.html#axzz0zTuNJFui

I agree with Fred that Freytag’s model is an easy and accessible jumping off point for younger students to understand the plot sequence of many fictional short stories. In fact, most students are probably unaware that they have already been exposed to this model as it has been used over and over in conventional fairy tales such as “Cinderella” or “Hansel and Gretel”. By exposing the pros and cons of Freytag’s model, teachers can introduce other approaches to narration in the form of theme and symbolism. For example, in “The Tell Tale Heart”, what do students think the “Evil Eye” or the beating of the heart represent?

I believe that to best engage students with a work it is imperative to ask rather than to tell, as I mentioned in class. More explicitly, ask students, after they have read the text or you have read it together, what shape the story takes in their minds. You could have them draw it out and jot down beside their drawing a few relevant points, and then share in small groups or with the class. This immediately forces the students to engage with the work critically, rather than sitting back and being told what shape the story is, and that their thoughts on the story must fit into the preconceived structure we are presenting.

A lot of people have commented on the extent to which Freytag’s model is useful when applied to contemporary fiction, so I’d like to focus on what other approaches might be employed in considering narrative structure. I am currently doing a project on teaching mythology, and have come across the Hero’s Journey, a narrative pattern originally described by Joseph Campbell. Campbell argues that there is a common path that heroes take in mythology, where they follow the same 17 steps, beginning in the “domestic world”, travelling into an alien space (for example, a foreign land or another world), and then ultimately returning to the domestic space after having mastered the other alien space. Campbell also uses a diagram, like Freytag, to illustrate his concept, and you can view it by following this link: http://www.kennesaw.edu/theatre/Hero-Journey/images/DIAGRAM.jpg. What is most interesting to me is that the Hero’s Journey is still common in many stories like Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings, and has even invaded Hollywood in The Lion King, the Matrix, and most famously, Star Wars. George Lucas has done a documentary detailing Campbell’s influence on his creation of Star Wars, and has made an effort to represent the Hero’s Journey in Luke Skywalker.

The purpose of this aside is to point out that narrative structure can be taught, through diagram, in a number of ways. If focusing on the action of the story with Freytag’s Pyramid is not an adequate or appropriate representation, then perhaps the Hero’s Journey can add insight for students if the main character is in a hero role. The Hero’s Journey, of course, focuses on the moral or psychological journey of the character rather than the physical action of the story, but might be a good alternate tool for the visual learners or for students who like a structured approach. Just like Freytag’s Pyramid, the Hero’s Journey is open for debate according to the story, as some characters might not complete all 17 steps. It might, however, be a better fit depending on the story. I suppose the most important thing is to treat each story separately and to choose the approach that is best for the story at hand, rather than trying to use the same diagram for each one.

Personally, I would still use Freytag’s Pyramid in my classes. I believe that it is a good starting point for students and provides a basic framework for those who might struggle with identifying the “shape” of a plot on their own. That being said, I really like the idea in the comment above about having the students draw their own shape depending on how they see the story (as discussed in class as well). If the story involves a hero, they might even end up drawing a circle (as Campbell does for the Hero’s Journey). In using Freytag’s Pyramid, however, I would probably start by providing my students with a story that carefully depicts each of the stages he identifies to give them a basic example to then diverge from. I think that The Tell-Tale Heart and The Lives of Boys and Girls in particular would be good stories to study after the students have become comfortable with the concept of narrative structure. They would definitely challenge the students to think critically about plot and about diagrams that appear to make the structures of all stories the same.

I think structures such as Freytag’s Pyramid and, as mentioned above, the Hero’s Journey are very useful in engaging students with literature. Sometimes when students are first starting to read critically and deconstruct pieces they have trouble sorting through the details, plot, characters, etc. I agree that these structures provide good jumping off points for younger readers and then later more advanced readers can use them with stories such as “The Lives of Boys and Girls” and “The Tell Tale Heart” to expand their analysis and see that not all narratives fit the conventional mold.

I would tend to agree with the last few post concerning the use of Freytag’s Pyramid in relation to the literary model of the Hero’s Journey. Freytag’s Pyramid does provide a useful framework to assist students in organizing aspects of complex stories and texts in order to begin the process of meaning making, which would otherwise be difficult when confronted with the intimidating task of procuring meaning from, what students might consider to be, a “closed” text. As previously mentioned, the Hero’s Journey is a model that has been used in the writings of ancient mythology (The Iliad, The Odyssey, etc…), but continues to find its niche in modern literary representations (The Hobbit, Harry Potter, etc…). The mythic hero’s journey often follows a linear path not subject to the temporal disruptions of certain metafictive devices and, therefore, is a more fitting model upon which Freytag’s Pyramid can be applied. For example, in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, the Hero’s Journey is in fact the character development of Bilbo Baggins. Freytag’s Pyramid can be applied by tracing the growth of Bilbo’s character beginning with (1) his call to adventure, (2) his separation from the known world, (3) his initiation into a new world, (4) the fellowship of close companions, (5) the guidance of a mentor (Gandalf), (6) a descent into darkness, (7) rebirth or resurrection, (8) the transformed hero’s return to the old world (http://www.novelguide.com/thehobbit/essayquestions.html). With the text following this linear pattern, the application Freytag’s Pyramid works well to elucidate the specific instances that define Bilbo’s growth and development as the novel’s hero.

However, that being said, the discussion of literature, even of the mythic hero’s journey, must not be restricted or confined to Freytag’s Pyramid. While Freytag’s model serves well in the exploration of plot and character development, its usefulness wanes in consideration of supplementary themes which require critical analysis and not simply the mere identification of important plot-based events. An example of the limitations of this model may be realized in considering a potential discussion on gender in Homer’s writings. The world of Homer, the realm of heroes, is one ruled by men. In fact, when women do appear in his writings, they often exist to serve some useful purpose for the male heroes. For instance, Iphigenia was ritualistically sacrificed by her father and uncle, king Agamemnon and his brother Menelaus, in order to persuade the gods to grant the Achaeans victory in the battle for Troy. Yet another Homeric example of women serving the purposes of male heroes is concerned with Chryses, a Trojan woman who is taken as a “prize” by king Agamemnon and later used as a means of appeasing the god Apollo. Freytag’s Pyramid often focuses on the linear action and plot-based thrust of a text, and generally does not facilitate discussion of concurrent yet differing themes, such as gender representations and stereotypes in Homer’s writing.

Therefore, while it is important to realize the value of Freytag’s Pyramid in organizing complex stories and allowing students to begin the process of meaning making, and it is equally important to be balanced enough to recognize the model’s shortcomings in its analytically-confining framework.

I think this model was designed or implemented as a suggestive tool for organizing some aspects of plot from which you can have your class delve into the parts in more detail. It does not seem to be dictating any particular format but is rather an umbrella or an overview from which several sub-plots and themes reside.

I am not a fan of Freytag’s Pyramid. The diagram is way to simple of a structure. I know some people have discussed using it as a simple model of narrative structure. The concern I have is that sometimes, when students learn something, they tend to place blinders on and might start to look at fiction through this narrow model. I now when I was taught this structure I tried to shoehorn all narratives into this model. Also I don’t necessarily think Freytag’s Pyramid is adding anything to the way we teach fiction. Will a student lose anything from not being taught this structure? Will they understand narrative structure less? I think it is more important to teach our students that there really isn’t any model and instead have them create their own.